Broad-Based Capital Injections

Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria (AMCON): Capital Injections

Purpose

AMCON was established “to acquire [NPLs] from [Nigerian] banks and annex the underlying collateral, [. . .] fill the remaining capital deficiency and receive equity and/or preferred shares in the affected banks as consideration” (Makanjuola 2015)

Key Terms

-

Announcement DateJanuary 28, 2010 (first public hearing on the AMCON Act)

-

Operational DateJuly 19, 2010 (signed into law)

-

Wind-down DatesAugust 5, 2011 (injection into bridge banks)

-

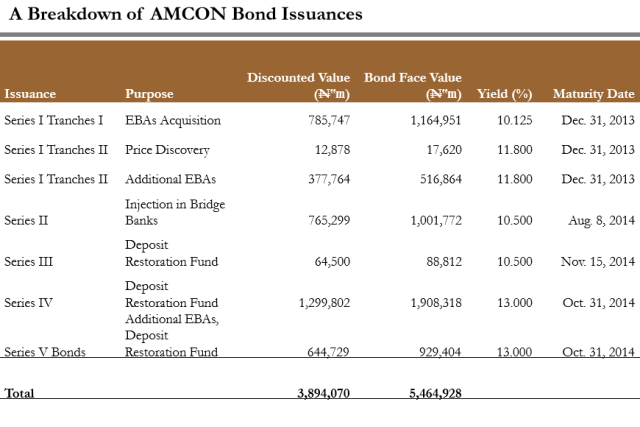

Program Size₦2.3 trillion (US$15.3 billion)

-

Peak Utilization₦2.3 trillion (US$15.3 billion)

-

OutcomesSuccessful—at great cost—at recapitalizing and selling banks

-

Notable FeaturesCreated bridge bank structure to accommodate institutions that did not meet initial deadline

Key Design Decisions

Part of a Package

Communication

Governance

Administration

Timing

Eligible Institutions

Program Size

Source of Injections

Individual Participation Limits

Capital Characteristics

Other Conditions

Fate of Existing Board and Management

Exit Strategy

Amendments to Relevant Regulation

Key Program Documents

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Broad-Based Capital Injections

Countries and Regions:

- Nigeria

Crises:

- Global Financial Crisis