Broad-Based Asset Management Programs

Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria (AMCON): Asset Management

Purpose

to stimulate the recovery of the Nigerian financial system through: 1. providing liquidity to the Intervened Banks and the non–Intervened Banks; 2. providing capital to the Intervened Banks and the non–Intervened Banks; 3. increasing confidence in bank balance sheets; 4. increasing access to restructuring/refinancing opportunities for borrowers

Key Terms

-

Launch DatesAnnouncement: January 28, 2010; Operational: July 19, 2010; First transfer: December 31, 2010

-

Wind-down DatesOperational as of 2021

-

Size and Type of NPL Problem32.8% of loans in 2009; loans comprised energy sector debt, margin loans secured by energy stocks, mortgages, and other corporate debt

-

Program SizeNot specified

-

Eligible InstitutionsAll banks in Nigeria; Open-bank

-

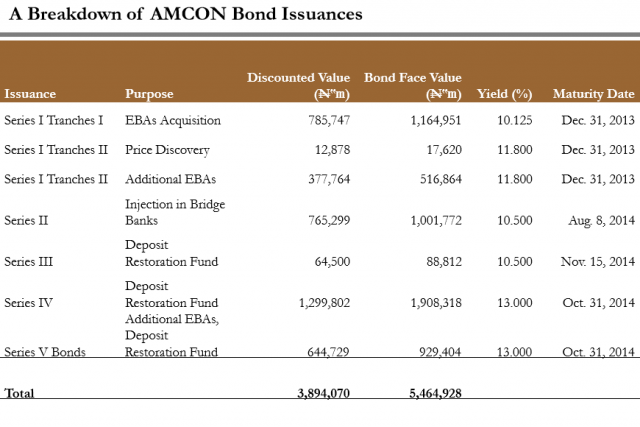

UsageAcquired ₦4.02 trillion for ₦1.76 trillion ($11.7 billion)

-

OutcomesNegative equity of ₦3.6 trillion in 2014

-

Ownership StructurePublic

-

Notable FeaturesThe CBN mandated that no financial institution could have more than 5% of their loans classified as assets eligible for purchase by AMCON

Key Design Decisions

Part of a Package

Special Powers

Mandate

Communication

Ownership Structure

Governance/Administration

Program Size

Funding Source

Eligible Institutions

Eligible Assets

Acquisition - Mechanics

Acquisition - Pricing

Management and Disposal

Timeframe

Key Program Documents

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Broad-Based Asset Management Programs

Countries and Regions:

- Nigeria

Crises:

- Global Financial Crisis