Reserve Requirements

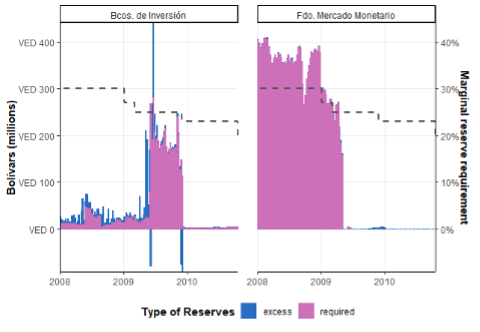

Venezuela: Reserve Requirements, GFC

Purpose

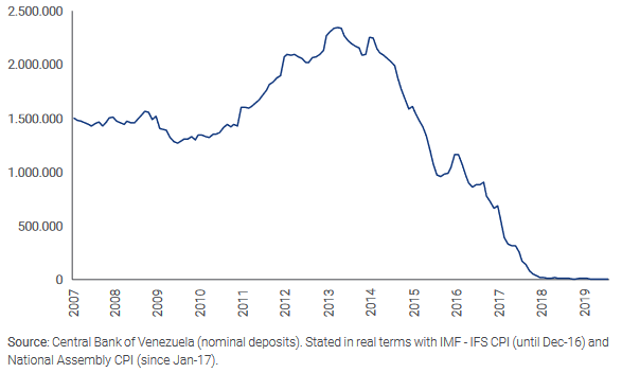

to increase liquidity in the banking sector

Key Terms

-

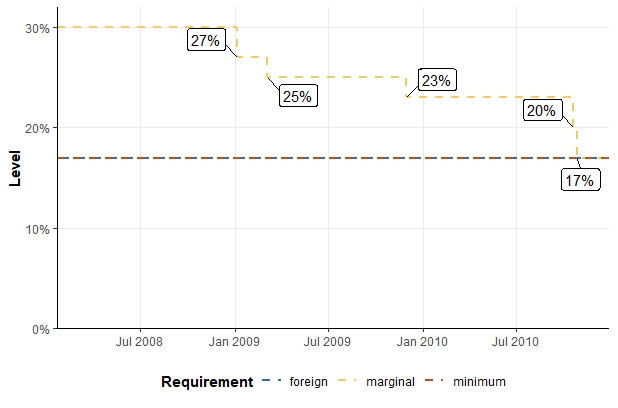

Range of RR Ratio (RRR) Peak-to-Trough30.0%–17.0%

-

RRR Increase PeriodJuly 2006

-

RRR Decrease PeriodDecember 2008–October 2010

-

Legal AuthorityLaw of the BCV

-

Interest/Remuneration on ReservesUnremunerated

-

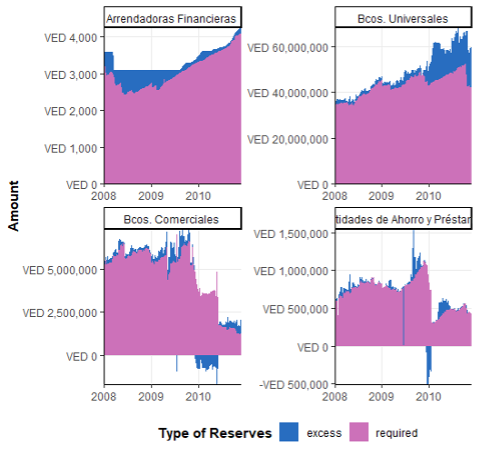

Notable FeaturesTimed before government bond issues Covered a broad population of banks and nonbank financial institutions, including money-market funds

-

OutcomesVEF 6 billion (USD 2.8 billion) liquidity released in the cut from 30% to 27%

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

Part of a Package

Administration

Governance

Communication

Assets Qualifying as Reserves

Reservable Liabilities

Computation

Eligible Institutions

Timing

Changes in Reserve Requirements

Changes in Interest/Remuneration

Other Restrictions

Impact on Monetary Policy Transmission

Duration

Key Program Documents

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Reserve Requirements

Countries and Regions:

- Venezuela

Crises:

- Global Financial Crisis