Broad-Based Asset Management Programs

US Resolution Trust Corporation

Purpose

To resolve, manage, and maximize the return on failed thrift asset portfolios with minimal taxpayer cost

Key Terms

-

Launch DatesAnnounced: February 6, 1989; Operational: August 9, 1989; First transfer: August 9, 1989

-

Wind-down DatesTransfer expiration: July 1, 1995; Last disposal: December 31, 1995

-

Size and Type of NPL Problem$80.8 billion in S&L assets (residential and commercial mortgages, consumer loans, mortgage-backed securities)

-

Program SizeNot specified at outset

-

Eligible Institutions747 resolutions with $465 billion (book value) in assets

-

Outcomes$455 billion (book value) disposed of, with 85% recovery ratio; losses of $87.5 billion

-

Ownership StructurePublic-owned

-

Notable FeaturesPut options allowed return of assets within a certain period; introduced securitization of commercial mortgages, joint venture sales of troubled assets, and broad use of putbacks

The savings and loan (S&L) industry experienced a period of turbulence at the end of the 1970s as sharply increasing interest rates caused much of the value of the industry’s net worth to evaporate due to its focus on long-term, fixed-rate mortgages. As a result, a period of rapid deregulation followed, and S&Ls, also called thrifts, engaged in increasingly risky behavior despite many being clearly insolvent. This trend of yield-seeking growth on the part of zombie thrifts forced the government’s hand as huge losses rendered the insurance fund backing the industry, called the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), essentially bankrupt. On August 9, 1989, the government passed the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA), which abolished the FSLIC and created the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC). The RTC had resolution and disposition authority over thrifts that had failed between January 1, 1989, and August 9, 1992 (subsequently extended first to September 30, 1993, and later to July 1, 1995). The government initially gave the RTC $50.1 billion in funding and the responsibility to manage tens of billions of dollars in failed thrift assets. Using a variety of resolution methods, such as purchases and assumptions, insured deposit transfers, and straight deposit payoffs, the RTC was able to successfully resolve 747 institutions, consisting of $455 billion (book value) in assets. These assets were often disposed of with methods ranging from direct sales, regional and national auctions, securitizations, and equity partnerships. Despite numerous concerns centered on gaps in its funding, inadequate internal controls, and problematic contracting procedures, the corporation managed a recovery ratio of approximately 85% from the disposal of these assets, and taxpayer losses amounted to an estimated $87.5 billion. The RTC shut down on December 31, 1995, and transferred $7.7 billion in remaining failed thrift assets to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

|

GDP (SAAR, nominal GDP in LCU converted to USD) |

$5.4 trillion in 1988 $5.7 trillion in 1989 |

|

GDP per capita (SAAR, nominal GDP in LCU converted to USD) |

$21,417 in 1988 $22,857 in 1989 |

|

Sovereign credit rating (5-year senior debt) |

Data not available for 1988 or 1989 |

|

Size of banking system |

$3.5 trillion in 1988 $3.6 trillion in 1989 |

|

Size of banking system as a percentage of GDP |

64.3% in 1988 62.7% in 1989 |

|

Size of banking system as a percentage of financial system |

Data not available for 1988 or 1989 |

|

5-bank concentration of banking system |

Data not available for 1988 or 1989 |

|

Foreign involvement in banking system |

Data not available for 1988 or 1989 |

|

Government ownership of banking system |

Data not available for 1988 or 1989 |

|

Existence of deposit insurance |

100% insurance on deposits up to $100,000 in 1988 and 1989 |

|

Sources: Bloomberg; World Bank Global Financial Development Database; World Bank Deposit Insurance Dataset; Cull, Martinez Peria, and Verrier 2018. |

The savings and loan (S&L) industry experienced a period of turbulence at the end of the 1970s as sharply increasing interest rates caused much of the value of the industry’s net worth to evaporate due to its focus on long-term, fixed-rate mortgages. As a result, a period of rapid deregulation followed, and S&Ls, also called thrifts, engaged in increasingly risky behavior despite many being clearly insolvent. This trend of yield-seeking growth on the part of zombie thrifts forced the government’s hand as huge losses rendered the insurance fund backing the industry, called the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), essentially bankrupt.

On August 9, 1989, the government passed the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA), which abolished the FSLIC and created the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC). The RTC had resolution and disposition authority over any thrifts that had failed from January 1, 1989, to August 9, 1992.FThis end date was extended twice. First, to September 30, 1993, and later to July 1, 1995.

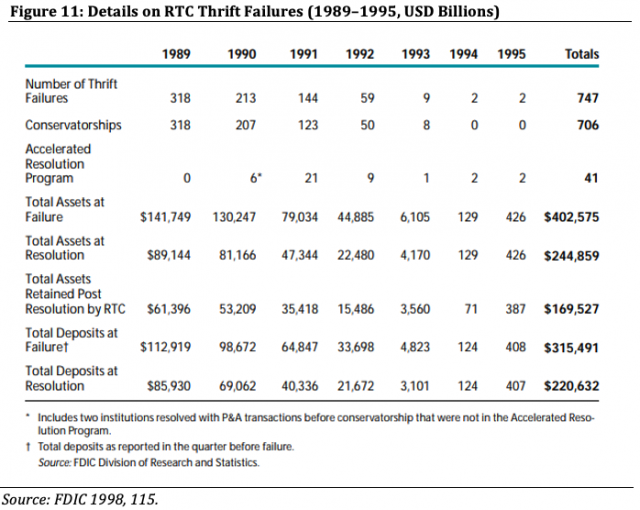

The RTC was given $50.1 billion in initial funding, as well as management duties over 262 failed thrifts with $115.3 billion in assets. Using a variety of resolution methods, such as purchases and assumptions, insured deposit transfers, and straight deposit payoffs, the RTC was able to successfully resolve 747 institutions and to dispose of $455 billion (book value) of their $465 billion (book value) in assets. These assets were often disposed of with methods ranging from direct sales, regional and national auctions, securitizations, and equity partnerships.

Many of these transactions were done by outside contractors, as the RTC did not have the operational capacity to readily dispose of the assets of these thrifts, particularly in the RTC’s limited timeframe. The contractors usually received management and disposition authority for nonperforming or less-marketable assets and had recovery ratios similar to those of other disposal methods.

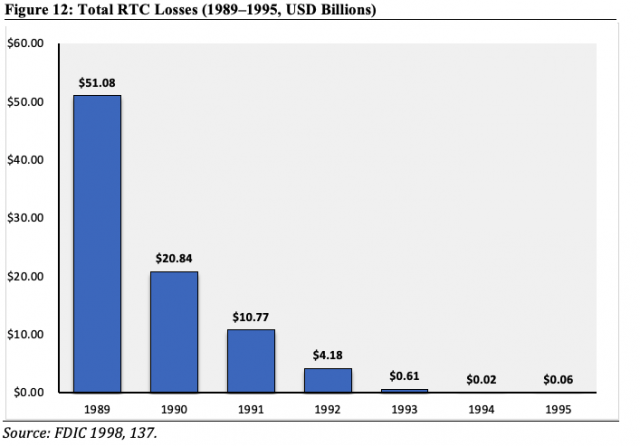

Throughout its lifespan, the RTC continued operations through a 21-month gap in its funding, questionable internal controls, incomplete or incorrect information systems, and inadequate contracting procedures. Despite these serious issues, the corporation managed a recovery ratio of approximately 85% from the disposal of these assets. Taxpayer losses were an estimated $87.5 billion of the $105.1 billion in funding that the RTC ultimately received. It was generally seen as successful in resolving the vast majority of these institutions and stabilizing a struggling industry. Just $7.7 billion in remaining assets were passed on to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation on December 31, 1995.

Key Design Decisions

Part of a Package

1

FIRREA created the Resolution Trust Corporation and abolished the Federal Home Loan Bank Board and Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation, while transferring the remaining duties of managing the FSLIC’s affairs to the FDIC-run FSLIC Resolution Fund (US Congress 1989, sec. 501). The Office of Thrift Supervision supervised privately held thrifts and closed them when they became insolvent. The RTC coordinated with the OTS at the point of failure to ensure a smooth transition. Any responsibilities for managing failed thrifts then fell on the RTC. The FDIC became responsible for failures once the RTC’s responsibilities ended.

Legal Authority

1

Title V, Section 501, of FIRREA established the RTC and its Oversight Board, as well. It stated specifically that the duties of the RTC were to “manage and resolve” depository institutions that were insured and had been placed into conservatorship by the FSLIC from January 1, 1989, to August 9, 1989. Additionally, it gave the RTC resolution authority over any S&Ls that would become insolvent in the three-year period following August 9, 1989 (US Congress 1989, sec. 501).

Mandate

1

In FIRREA, Congress gave the RTC several mandates that often conflicted with one another. The RTC was required to:

- Maximize the net present value (NPV) of the return on any asset disposition efforts or sales.

- Minimize the impact that these disposition efforts would have on local real estate and financial markets.

- Maximize both the “preservation and affordability of residential real property for low and moderate-income individuals” (US Congress 1989, sec. 501).

These mandates could conflict. For instance, the first objective might involve the sale of as many assets as possible, as quickly as possible, to ensure the highest rate of return. In doing so, however, this could be considered “dumping” and potentially impact local real estate and financial markets. Additionally, compliance with the affordable housing mandate could involve reserving certain portions of the asset portfolio for lower-income buyers, which could increase costs to the RTC (FDIC 1998). FIRREA and RTCRRIA gave the RTC mandates to include MWOBs in their contracting agreements and established an Office of Minority and Women Outreach and Contracting Program. In 1992, for instance, MWOBs received approximately $323 million, or 28%, of total fees, which was close to the 30% target that RTC had set (GAO 1993b, 3).

Communication

1

Much of the RTC’s early history was fraught with severe political backlash, primarily due to the speed of its cleanup and the allocation of its funds. Representatives Frank Annunzio (D-IL) and Carroll Hubbard (R-KY) were two of the program’s earliest detractors. Representative Annunzio went on record saying, “The American people are disgusted with the lack of progress of the savings and loan cleanup. Every constituent is deeply frustrated with the slow pace of the RTC and the Justice Department.” He also railed against the company’s extensive use of put options, which provided acquirers a “free ride period” (RTC Task Force 1990b).

Representative Hubbard echoed this sentiment, stating that “support for this operation is gone” and that the corporation “cannot get another dollar of public funds for this operation until the taxpayers’ interests come first . . .” (RTC Task Force 1990b).

Both of these accounts, as well as those of others on the House Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs, signified a dwindling pool of public support, if not one that had already completely evaporated so soon into the program’s lifespan.

In this same 1990 congressional session, then–Chairman of the Oversight Board Nicholas Brady, the Treasury secretary, explained that the government’s primary goal when creating the RTC, first and foremost, had been to protect depositors. Brady addressed the claim of being too lenient on thrifts: “We are not bailing out shareholders of S&Ls, we are not bailing out management, we are not in this to preserve the institutions; in fact, many will be lost. [Money] spent [is] spent to protect depositors” (RTC Task Force 1990b). Much of his communication to the committee was that the problems facing the industry were much more widespread than previously thought and that the RTC wasn’t in the business of speculating on future losses. He did say that, based on the current economic climate, losses were likely to range from $90 billion to $130 billion, which ultimately was slightly more than what the RTC ended up sustaining. Brady ended his statement by reaffirming the RTC’s original commitment made by President Bush, to “protect depositors, clean up the industry at the least cost to the taxpayers, and punish the criminals” (RTC Task Force 1990b).

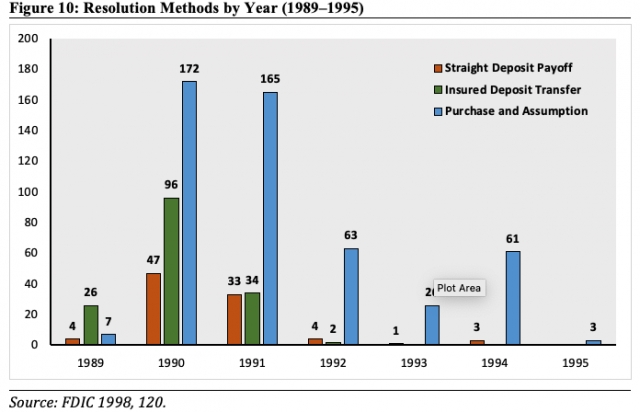

The philosophy of “depositors first,” according to RTC resolution data, showed up in the composition of the corporation’s resolution strategies throughout its lifespan. Early on, the RTC opted to engage in more rapid resolution methods via straight deposit payoffs and insured deposit transfers for many of the thrifts that had been in conservatorship prior to FIRREA. Using these tools, depositors who had been in limbo were made whole much more quickly than if the RTC had used the marketing and solicitation tactics necessary to complete a purchase and assumption transaction, despite their usually resulting in lower costs (FDIC 1998).

William Seidman, then–chairman of the RTC, reinforced the ideas in Brady’s testimony with his own about two years later. Seidman explained that, of the 646 institutions that the RTC had become responsible for, it had closed 511, and approximately 16 million depositors, with average balances of about $9,000, had been protected. In his rundown on the program’s operations, Seidman also talked about the RTC being, “committed to a philosophy of openness and public accountability” (RTC Task Force 1992). To this end, Seidman cited (1) the establishment of a “Public Reading Room,” which synthesized more than 29,000 inquiries from the RTC’s creation through July of 1991, and (2) the creation of regional “Public Service Centers,” which processed about 20,000 inquiries in the same time period (RTC Task Force 1992).

Because the Oversight Board and RTC executives were required to regularly meet with members of Congress, these publicly available testimonies and discussions made up a substantial part of the RTC’s communications efforts.FThe RTC also faced a substantial amount of criticism from the General Accounting Office (GAO), now the Government Accountability Office, during its early years. The specifics, as well as the RTC’s subsequent efforts to address them, are outlined in the “Evaluation” section.

Ownership Structure

1

Under the original legislation, the FDIC acted as the day-to-day manager of the RTC and the RTC’s board of directors was identical to the FDIC’s. The RTC was responsible for any administrative costs (US Congress 1989, sec. 501). This structure was created because the FDIC did not want to “shoulder the burden of conducting the S&L cleanup without having any say in how the cleanup would be run” (Davison 2005). While the Bush administration did not like the idea of ceding further control of the RTC to the FDIC, they recognized that sharing responsibility with the FDIC would provide it some insulation in case the RTC ran into problems (Davison 2005).

Governance/Administration

1

The members of the Oversight Board consisted of the following:

- The secretary of the Treasury;

- The chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors;

- The secretary of Housing and Urban Development; and

- Two “independent members” appointed by the president with the advice of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs. These members had three-year terms and had to be from different political parties (US Congress 1989, sec. 501).

The board had several important functions, such as the ability to establish national and regional advisory boards, evaluate audits conducted by the Office of the Inspector General, and generally review the corporation’s performance. In addition, a variety of internal controls were adopted with the passage of FIRREA.

- The RTC received an annual audit by the General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office) with the help of an independent CPA.

- The RTC was required to submit annual reports that included audited financial statements.

- The Oversight Board was authorized to remove the FDIC as exclusive manager if the FDIC failed to adhere to the strategic plan, failed to maintain or achieve financial goals, committed fraud or abuse, and/or failed to obtain value that was close to the market value of the assets it was selling.

- The clearly defined sunset date of the corporation acted as an internal control mechanism as well, to ensure that the government would not remain as a major player in the mortgage market for longer than necessary (US Congress 1989, sec. 501).

The RTC was authorized to have contractors take part in its resolution activities, provided they complied with any relevant FIRREA provisions and acted as a fiduciary for the assets under contract. These contractors could not be in any way affiliated with or be employed by any RTC-managed institution.

Additionally, the RTC Oversight Board was required to appear twice a year before the House Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs and answer questions about the RTC’s activities. The board also published annual reports from 1989 to 1995. Section 501 of FIRREA specified a “semiannual appearance” by the members of the RTC’s Oversight Board to report on:

- Matters of thrift resolution and asset disposition;

- Cost estimates for remaining resolution and disposition efforts;

- The impacts that asset disposition efforts were having on local real estate and financial markets; and

- Estimates of remaining costs and exposure, additional income, and funding needs (US Congress 1989, sec. 501).

The annual reports, which were publicly available, contained audited financial statements from the corporation, overviews of its asset disposition methods, and comments from the Oversight Board of the RTC (later the Thrift Depositor Protection Oversight Board) about the corporation’s operation. Extensive statistics about the number and cost of resolutions for individual institutions, as well as the number of conservatorships, were also made publicly available through these reports (RTC 1995a).

However, the passage of the Resolution Trust Corporation Refinancing, Restructuring, and Improvement Act of 1991 on December 12 streamlined much of the RTC’s administrative structure and gave it more freedom to act independently. Some of the issues included “the RTC’s need for interim funding and concerns that its dual board structure was cumbersome and inefficient (for example, the Oversight Board had to approve policies recommended by the RTC/FDIC board . . .” (Shorter 2008, 2). Ultimately, RTCRRIA did the following:

- Repurposed the RTC’s Oversight Board as the Thrift Depositor Protection Oversight Board, which no longer included the secretary of Housing and Urban Development (US Congress 1991b, sec. 302);

- Abolished the RTC’s board of directors (US Congress 1991b, sec. 310);

- Removed the FDIC as the exclusive manager of the RTC (US Congress 1991b, sec. 314); and

- Established the Office of the Chief Executive Officer of the RTC. The CEO was a presidential appointee (US Congress 1991b, sec. 201).

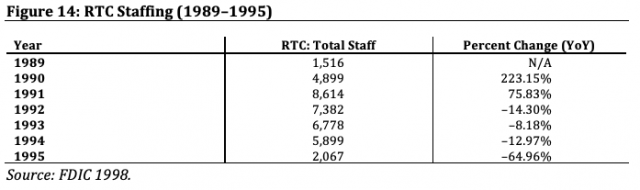

While the RTC was originally envisaged to not have very many employees, staff levels ballooned as well after 1989, rising more than 200% and remaining elevated through the corporation’s “peak” years (i.e., 1989–1991). Around 2,000 employees were transferred to the FDIC when the RTC closed its doors at the end of 1995. See Figure 14 for a breakdown of RTC staffing levels.

Program Size

1

The OTS appointed the RTC as the conservator of any previously FSLIC-insured thrifts that became insolvent within the period specified by FIRREA (US Congress 1991b, sec. 201). FIRREA imposed a maximum outstanding obligation limit of $50 billion on the corporation, calculated as the sum of (1) total contributions from REFCORP; and (2) total outstanding obligations, minus the sum of (a) the total amount of cash held and (b) the amount equal to 85% of the RTC’s estimate of the fair market value of other assets held (US Congress 1989). This language required the RTC to return to Congress if it needed more funding, which it did on two separate occasions. Some of the funding came with a deadline that mandated any unused funds to be returned to Congress. The RTC had to return to Treasury $18.3 billion of the $25 billion allowed under the RTCRRIA because it was not used before the deadline of April 1, 1992, even though the funding was appropriated only in January of that same year (RTC 1992). This event marked the beginning of a 21-month-long funding drought for the corporation that severely hampered its resolution efforts (FDIC 1998). Because of its loss-bearing function, the RTC was, predictably, quite controversial, but the decision to so closely tie its funding to Congress remains quite controversial.

Funding Source

1

The funding of REFCORP was a topic of substantial congressional debate. While the RTC could have been funded completely through appropriations, the costs would have more significantly impacted the federal deficit in the short term (Adams, Peck, and Spencer 1992). Of the original $50.1 billion, $18.8 billion was on budget, appropriated by Congress, and expected to be used by the end of the 1989 fiscal year (September 30, 1989). Off-budget initial funding totaled $31.3 billion, with $1.2 billion provided by Federal Home Loan Banks and $30.1 billion raised by REFCORP. REFCORP was managed by the FHLBanks system and issued long-term (30- to 40-year) debt onto public securities markets to obtain funding. With this funding, REFCORP then purchased nonvoting RTC capital certificates that paid no dividends. Interest on the bonds was paid by the FHLBanks and the US Treasury (FDIC 1998). Structuring the funding this way, Bush administration officials said, “would allow [the administration] to have an increased revenue base under which to finance Federal programs without increasing the deficit or exceeding Gramm-Rudman targets” (Dowd 1989).

While the original $50.1 billion was a mix of taxpayer, REFCORP, and FHLBanks funding, the RTCFA of 1991 and the RTCRRIA of 1991 gave the RTC $30 billion and $25 billion, respectively, in taxpayer funding. These funding infusions brought the total to $105.1 billion for loss sharing (US Congress 1991a; US Congress 1991b). Approximately $87.5 billion in direct taxpayer losses were ultimately incurred (FDIC 1998).

All loss funds were provided via Congressional appropriations, REFCORP, or FHLBanks, and the RTC was to take on any losses realized. Losses were calculated by determining how much the RTC needed to pay to cover depositor claims, then estimating how much it would recover from the sale of that institutions’ assets. Any amount recovered from these sales was considered working capital.

The RTC also had the capacity to file in bankruptcy court to recover on losses. For instance, the FDIC and RTC both filed a $6.8 billion claim against Drexel Burnham Lambert, Inc. in 1990 due to heavy junk bond–related losses incurred by 45 institutions under its management. In the end, the firm settled through a series of structured settlements that entailed periodic cash payments to the FDIC, RTC, and dozens of failed private institutions that had been clients of the firm. Drexel’s bankruptcy arrangements set aside a percentage of the firm’s estate to pay, on a pro rata basis, the litigators (FDIC 2018).

Eligible Institutions

1

The newly created Office of Thrift Supervision was responsible for placing any insolvent thrifts into conservatorship and appointing the RTC as the resolution authority (US Congress 1989, sec. 201). Any thrifts that had been in conservatorship from January 1, 1989, to August 9, 1989, which was the day FIRREA was passed, were eligible (US Congress 1989, sec. 501). Additionally, the OTS could appoint the RTC as a conservator for any failed S&Ls for three years following the passage of FIRREA (US Congress 1989).

As part of its mandate in FIRREA, the OTS was required to establish new minimum capital requirements for S&Ls. On November 8, 1989, these requirements were entered into the Federal Register (see Figure 8, below): (1) a risk-based capital requirement of 8%, equivalent to the level global bank regulators had recently agreed in the first Basel Capital Accord; (2) a leverage ratio requirement; and (3) a tangible capital requirement (FR 1989).

A notable design aspect in these requirements was the decision to “grandfather” portions of supervisory goodwill—the kind that allowed thrifts to overstate their capital levels to begin with—into the calculations of tangible and core capital levels over a limited timeframe. Specifically, the requirements allowed a percentage of supervisory goodwill—obtained through “the acquisition, merger, consolidation, purchase of assets, or other business combination”—if it had been recorded on or before April 1989 (FR 1989). This amount gradually declined starting in 1992 and was eliminated after 1994 (FR 1989).

Noncompliance was punished differently if it was documented before or after 1991. Thrifts that did not meet these requirements prior to that year faced restrictions on asset growth and were required to submit capital plans to the OTS that detailed how they would satisfy the requirements. After 1991, the penalties for falling under the standards were more severe. The OTS prohibited asset growth; reduced the rates paid on savings accounts; prohibited taking new deposits and issuing new accounts; and even prohibited lending, the purchase of loans, and other investments (FR 1989). According to FDIC Senior Economist Lynn Shibut, there were no quantitative “triggers” for resolution, however, so only institutions that were insolvent were closed by the OTS.

Eligible Assets

1

The vast majoriy of the RTC’s assets were real estate related, with about half consisting of commercial and residential mortgages. All other types, such as owned real estate, other assets/loans, and securities made up the other half of its portfolio (FDIC 1998).

Acquisition - Mechanics

2

Initially, the RTC was eligible to act as a resolution authority for institutions put into conservatorship from January 1, 1989, to August 9, 1992. This horizon was extended twice—first, to September 30, 1993, with the passage of the Resolution Trust Corporation Refinancing, Restructuring, and Improvement Act of 1991, and finally to July 1, 1995, with the passage of the Resolution Trust Corporation Completion Act of 1993 (US Congress 1991b; US Congress 1993).

The RTC resolved 747 insolvent institutions through a variety of conventional resolution methods. These were purchases and assumptions, insured deposit transfers, and straight deposit payoffs. P&As were the RTC’s preferred method of resolution, as they were the most cost-effective.FIt is important to note that thrifts that were healthier tended to be selected for P&As, while those with less franchise value or negative equity were more likely to be resolved with either deposit transfers or payoffs. In general, the underlying condition of the thrifts was a bigger determinant of costs than the method of resolution. However, they required a lengthy marketing, valuation, and bidding process that IDTs and SDPs did not need. About two-thirds of resolutions were done through P&As. By the spring of 1990, the RTC also allowed individual branches of failed thrifts to be purchased, thus encouraging a broader group of acquirers to participate (FDIC 1998, 131).

IDTs were slightly more cost-effective than an SDP due to the agent (purchasing) bank’s ability to offer its services to new potential depositors (FDIC 1998, 19). Resolution via a deposit transfer was also preferable because it allowed depositors continued access to their funds. SDPs were used earlier on but were costlier than the other two due to the RTC having to directly pay off all deposit liabilities and take on all assets.

In the event that a resolution prior to insolvency could save taxpayers money, the RTC and OTS developed the Accelerated Resolution Program on July 10, 1990. The corporation theorized that early conservatorship for thrifts that still had some market value would cost more to the taxpayer due to the negative public connotation around conservatorship. The goal behind the ARP was to provide an expedited avenue of assistance aside from conservatorship that still had substantial franchise value and had not been declared insolvent by the OTS. Rather than use broad solicitation methods, the RTC marketed more selectively, using the FDIC’s National Marketing List (the List) in conjunction with the OTS (FDIC 1998). The List aggregated sets of potential acquirers into one database, and the RTC Marketing Section targeted specific potential buyers based on the types of assets that it was scheduling to sell (RTC 1991). Valuation was generally more thorough because the corporation wanted all of a failed thrift’s assets to be offered at sale. While conventional RTC resolutions sometimes had assets sold before the resolution process, ARPs had all of a thrift’s assets on sale. No put options were available for ARP transactions.FHowever, there were standard representations and warranties agreements on all ARP transactions. Generally, loans were sold to asset-only acquirers at higher prices than the RTC’s valuations, though lower than prices the FDIC valued them at. This reflected the difference in valuation methodologies, where the RTC was more likely to accept bids that were lower because it tended to account for marketplace realities (FDIC 1998).

Institutions that were resolved via the ARP all were done through P&As, and 41 of the 747 resolutions were ARP. The program’s effect was limited in part due to the RTC’s appropriation expiring on April 1, 1992, and the 21-month funding gap that followed. The costs for resolutions under the program were much less, and a greater percentage of assets tended to be purchased (FDIC 1998). However, the underlying financial condition of the thrift was a more significant factor in determining costs than was the chosen strategy.

Acquisition - Pricing

1

Because the RTC functioned as the interim replacement for an insolvent deposit insurer—FSLIC—all thrifts that the OTS put into conservatorship were given the RTC as a conservator. Therefore, the initial acquisition of a failed thrift was at book value, less any provisions that the firm had made at that point. RTC staff then determined the value of the failed thrift’s assets, which helped allocate loss funds and served as a basis to evaluate franchise sale bids.

Management and Disposal

3

Much of the corporation’s early efforts in resolution focused on tackling the institutions that had the least franchise value and were taking on the most losses. To quickly resolve these institutions, the RTC relied heavily on straight deposit payoffs and insured deposit transfers. The RTC conducted more SDPs in the earlier years of its lifespan due to the number of institutions that had been deemed insolvent for an extended period of time or were located in acutely distressed markets and had very little franchise value.FSee Figure 1 for a detailed breakdown of resolution methods.

IDTs and SDPs, for these institutions, were the only real methods of resolution left, per FIRREA standards. Because of these conditions, the majority of IDTs and SDPs were conducted from 1989 through 1991, when the stresses of the crisis were most prominent (FDIC 1998). These were the years that the RTC incurred the vast majority of its losses.

For assets that were held onto after resolution, the RTC employed a number of novel measures to sell its more distressed assets first, while recovering more from their disposition than it might otherwise have received.

Pricing. The RTC hired contractors to perform Asset Valuation Reviews (AVRs), which were estimates of the value of assets held by failed thrifts. These estimates were used to evaluate franchise sale bids. Early on, the RTC’s AVR methods were critiqued for potentially overstating the value of receivership assets, due to the staff’s lack of asset sales experience and its decision to sample portfolios prior to acquisition.FPrior to 1991, valuation took place on samples that were chosen prior to acquisition, or before the acquirer purchased the “good” (i.e., performing) assets and left the “bad” assets to be handled by the corporation. Because these valuations were then projected across the rest of the portfolio, this may have overstated the value of assets remaining in receivership (RTC 1991). The RTC ultimately overhauled its AVR framework in 1991 and began using more sophisticated statistical techniques to better approximate the recovery value for all sampled assets. Additionally, for each sample the corporation hired “a single experienced contractor” to do all the AVR work (RTC 1991).

Regional and National Loan Auctions. A total of 20 regional and national loan auctions were conducted from June 1991 to December 1995. The corporation established the National Loan Auction Program in September 1992 to better dispose of the considerable pool of “hard-to-sell” assets (FDIC 1998). These auctions generally lasted about two to three days, and potential bidders were required to put down a $50,000 deposit to participate (FDIC 1998).

Approximately 141,000 loans, with a book value of $4.9 billion, were sold for about $2.4 billion, netting the RTC an average recovery value of about 48.8% of book value. Total national auction costs ran to about $30.6 million (FDIC 1998).

There was a wide variety of loans available for sale, and one of the challenges that the RTC faced was that small loans, just like the larger, more complex ones, required the same amount of administrative due diligence. Regional auctions were designed to sell this large inventory of small assets that the RTC had. Thus, it was often in the RTC’s best interest to package and quickly dispose of them to increase its capacity to handle larger accounts. National auctions grew out of the increasing number of nonperforming and hard-to-sell loans, which eventually prompted the RTC to relax its criteria for what loans would be allowed in the auctions. While the program originally was designed for nonperforming loans, eligibility widened as the auctions went on to include performing loans that were not able to be securitized, were underperforming, or had other problems that made them unmarketable. Owned real estate generally included any real property that had a title that was acquired by foreclosure, a deed in lieu of foreclosure, or that was intended to protect the thrift’s interest in any residual debts that had been contracted. Broker listings, normally conducted by SAMDA contractors, were the primary method through which the RTC disposed of ORE, but auction methods become more popular as its ORE holdings grew (FDIC 1998).

Additionally, the corporation did not want to disenfranchise smaller potential bidders and, as a result, stratified some loan packages in its National Loan Auction Program to keep their value below $2 million so that the RTC’s Small Investor Program could market them to smaller, noninstitutional investors. ORE was a particularly challenging portion of the RTC’s portfolio. Because it was often acquired under particularly stressful circumstances, ORE was often lumped into pools with other nonperforming loans and related instruments. Significant growth in the corporation’s ORE portfolio forced it to turn to an auction method to more rapidly dispose of its portfolio of these assets (FDIC 1998).

Use of Contractors. Since the RTC was so quickly expected to resolve and dispose of hundreds of billions of dollars of assets, FIRREA specifically mentioned that the RTC would be allowed to use private contractors so long as the corporation determined that “. . . utilization of such services [were] practicable and efficient” (US Congress 1989).

RTC contractors, operating under Standard Asset Management and Disposition Agreements, were normally given loans or asset pools that were either nonperforming or had less franchise value overall. The RTC did not have the staffing nor the requisite experience in asset disposition to properly value, market, and sell many of the hard-to-sell assets, and thus chose to rely more heavily on private contractors (FDIC 1998).

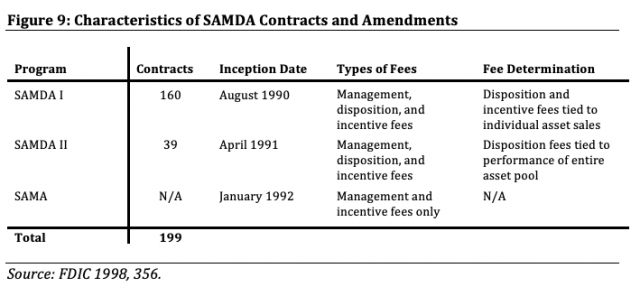

SAMDAs typically had terms of three years but had the option of three one-year extensions, if needed. Original SAMDA contracts, called SAMDA I, had their fee structures tied to the sales of individual assets. SAMDA II contracts, which began in April 1991, had their disposition fees tied to the performance of the entire pool of assets that the contractor was managing. These contracts could also be amended to include only asset management and not disposition responsibilities.FThese amendments were called Standard Asset Management Agreements, or SAMAs, which were amendments to the structure of a SAMDA contract. Per the name of the contracting agreement, these entities, which were often asset or property management firms, had full management and disposition authority. Entities under a SAMDA contract were also mandated to enter into subcontracting agreements with other firms to help them speed up parts of the disposition process. A total of 199 SAMDAs were issued to 91 contractors, covering about $48.5 billion in failed thrift assets (FDIC 1998).

Securitization. The RTC helped pioneer a substantial private securitization effort starting in December 1990. This initiative was done because many of the assets had several undesirable qualities, such as “documentation inaccuracies, servicing problems, and late payments” (FDIC 1998). As the need to reduce the size of the RTC’s balance sheet increased, so too did the types of collateral that the corporation made eligible for securitization. Other assets, including commercial mortgages, multifamily properties, and consumer loans, were included as time went on. The RTC was forced to deal with informational deficiencies, particularly with its commercial securities, that hampered its sales. The Corporation would eventually author Portfolio Performance Reports (PPR) that would go on to become industry standards amongst issuers of securities (FDIC 1998).

To ensure that there would be sufficient demand for private securities, the RTC initially pushed for a government guarantee on them. However, the RTC’s Oversight Board did not support a government guarantee due to the corporation’s temporary nature and the potential for its securities to compete with others issued by the US government. When this failed, the RTC instead backed them with cash collateral for external credit enhancement features, such as overcollateralization, subordination, and cash reserve funds to ensure they would receive high ratings (FDIC 1998). The cash reserves often were in excess of 30% to 40% (Effros 1997).

To increase the pool of potential investors, the RTC also tied the interest rate of many of the residential MBS to the London interbank offered rate, making them more attractive to international buyers. Additionally, many of the commercial securities also had substantial representations and warranties, such as repurchase agreements and environmental indemnifications, which made purchasing them more attractive (FDIC 1998).

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were involved in an initiative called the Agency Swap Program, in which they either engaged in cash sales to buy pools of conforming residential mortgages or swapped these pools of mortgages for Fannie and Freddie securities. Due to their agreements with the RTC, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac also required significant credit enhancement on the part of the corporation to take on the pools of loans.FThis credit enhancement was usually in the form of cash reserves withheld from the purchase price of the loan pool. Approximately $6.1 billion of conforming residential mortgages were sold to the GSEs (FDIC 1998).

The RTC also launched a commercial securitization program in January 1992, which was one of the precursors to the commercial real estate securitization boom that followed shortly after the S&L crisis. These commercial securities comprised commercial loans that often had missing documentation, were in arrears, or had multiple original lenders. As a result, large credit-enhancement levels were necessary to obtain high credit ratings from rating agencies. There were a total of 72 residential and commercial MBS transactions, totaling $42.2 billion (FDIC 1998).

Equity Partnerships. The RTC formally introduced these partnerships in the fall of 1992, in part due to the huge inventory of nonperforming loans that it still held. In these partnerships, the RTC acted as a limited partner (LP) and provided troubled assets while a private entity acted as the general partner (GP) and manager of these assets. Equity capital was provided by both the LP (as asset pools) and the GP. Additionally, the GP received a pro rata portion of the proceeds from the net recovery on any assets (FDIC 1998).

The corporation believed that, for hard-to-sell pools of assets, joint ventures were a more cost-effective method of disposing of them compared to a direct sale (FDIC 1998). These partnerships later were expanded and geographically parsed out so that the corporation could more widely market them to smaller, noninstitutional investors, similar to their auction-based efforts.

The RTC was originally scheduled to be shut down on December 31, 1996. However, this shutdown date was moved up to December 31, 1995, with the passing of the Resolution Trust Corporation Completion Act in 1993 (US Congress 1993). If any thrifts remained in conservatorship or receivership after December 31, 1995, the FSLIC Resolution Fund became responsible for them (FDIC 2018). Additionally, all assets and liabilities of the RTC were transferred to the FRF, which then transferred any profits from the sale of these assets to REFCORP to help it pay off any residual debts.

In total, the RTC used seven different types of equity partnerships over the course of its operation.FSee FDIC 2018, chapter 17, for more information on equity partnerships. A total of 72 partnerships, comprising $21.4 billion (book value) in assets, were created, with the LP and GP receiving proceeds based on their share of ownership (FDIC 1998).

Asset putback provisions, or put options, were often used in lieu of more robust representation and warranty agreements early during the S&L crisis. The initial terms on these provisions were anywhere from 30 to 90 days but were extended to 18 months in the spring of 1990. The RTC sold about $40 billion in assets that had put options on them, and more than $20 billion were returned, indicating that institutions often picked and chose which assets to keep (FDIC 2018).

The RTC was initially hesitant to include robust, market-oriented R&Ws, as they represented, in theory, a substantial source of potential liabilities if the asset was not of sufficient quality or managed well. However, a product without R&Ws was seen as being potentially riskier. Initially, the RTC tried to avoid putting R&Ws on its sales of loans largely due to a lack of experience, and in some cases opted to use put-option clauses as a way to avoid using them (Moreland-Gunn, Elmer, and Curry 1996). The risk-based concerns, as well as the RTC’s relative lack of experience in selling troubled assets, made selling much of its loan portfolio much more difficult throughout the early 1990s (Moreland-Gunn, Elmer, and Curry 1996). As a result, the RTC eventually ended up expanding its R&W criteria to be more in line with what market participants were offering (Moreland-Gunn, Elmer, and Curry 1996).

Valuation for loan sales was normally done through appraisals and in consultation with Wall Street investment houses and other, similarly qualified firms. For structured transactions, it used an asset valuation methodology called derived investment value (DIV), which “attempted to value individual assets packaged for portfolio sales as investors would perceive the value of those assets” (FDIC 1998). This threshold was, in March 1991, reduced to 70% with an amendment to FIRREA to accelerate the disposition process (FDIC 1998).

Timeframe

1

The RTC Completion Act of 1993 amended both the sunset and eligibility dates to December 31, 1995, and July 1, 1995, respectively (FDIC 1998). The 30- to 40-year REFCORP bonds are still being paid down today, with the last bonds set to mature in 2030. Total interest costs were projected to be around $88 billion (GAO 1996).

FIRREA and its related legislation mandated the RTC to publish detailed, audited reports and to give access to any information necessary to conduct analysis on the corporation’s performance to other organizations, such as the General Accounting Office, now the Government Accountability Office (US Congress 1989, sec. 501). One of the many reports that GAO released addressed the myriad funding concerns, information system inadequacies, and administrative difficulties that the RTC dealt with during the crisis (GAO 1993a). GAO even went as far as to “designate the RTC as one of 18 high-risk institutions that were particularly vulnerable to fraud, waste, and mismanagement” (GAO 1995a).

Funding Concerns. The most evident example of the corporation’s serious funding troubles was the $18.3 billion in loss funds that the RTC was required to return after April 1, 1992, because it was not able to use all the funds before the appropriation from RTCRRIA expired (FDIC 1998). Just as the initial funding of the RTC was politically contentious, the prospect of providing it with more funds—and, consequently, more taxpayer exposure to losses—was something that neither party was keen on doing (Davison 2006b). Neither party in Congress wished to appropriate more funds to an institution that they felt had resolved institutions too slowly. While the Senate proposed a straightforward additional $30 billion in loss funding for the corporation, several proposals emerged in the House. These ranged from requiring any additional funding above a certain threshold to be deficit-neutral and a proposal to ‘bail-in’ state governments where a high number of failed thrifts existed by forcing them to pay 25% of the costs. In the end, however, the Resolution Trust Corporation Funding Act of 1991 that ended up passing largely resembled the original $30 billion Senate bill with some additional requirements on reporting, minority contracting, management reforms, and affordable housing provisions (Davison 2006b).

GAO explained the importance of continued RTC funding, as the Office of Thrift Supervision had already flagged 83 additional thrifts with $46 billion in total assets that were likely to fail in the next year (GAO 1993a). Without funding, the RTC would have been unable to undergo its resolution procedures, resulting in costly delays. This gap in funding would cause the number of resolutions to fall to just 60 in 1992, compared to 211 in 1991, and the average number of days until resolution to rise to 596, from 429 in 1991 (FDIC 1998).

The funding of REFCORP was expensive for the FHLBanks, which were required to pay interest on its bonds. It was predicted that such contributions to REFCORP would substantially reduce the banks’ net income and, as a result of the adverse effect on the banks’ ability to pay dividends to members, the thrift industry’s net income would also decline. This, however, was a deliberate decision to partially bail-in the thrift industry, though ultimately the amount provided by the FHLBanks—both outright and in interest payments—was relatively minor. Additionally, the issuance of the REFCORP bonds themselves also was a point of contention. GAO reported that long-term REFCORP bonds were sold at rates that were higher than equivalent Treasury debt, which resulted in an additional $3 billion in interest costs to REFCORP that could have potentially been avoided (GAO 1991).

Information Systems. GAO also criticized the RTC’s inefficient and inadequate Real Estate Owned Management System (REOMS), citing that many of the records were missing key data points. The report specifically mentioned that “[a]bout 80 percent of the unsold properties on REOMS lacked one or more key data elements, such as listing price, date listed for sale, and identification of broker” (GAO 1992). These were not minor details but crucial pieces that were missing that could seriously delay sales and acquisitions. However, the report did note that the corporation had been in the process of rolling out a “data integrity program” but that persistent errors in an estimated 37% of REOMS records still existed (GAO 1993a). The RTC’s Asset Manager System (AMS), which tracked income and expense data for contractors, as well as automated payments to them, also saw its fair share of criticism, centering on the calculation of fees, transferring data effectively, and validating correct payment amounts to contractors (GAO 1992).

Because of the lack of data, GAO reported that the RTC’s sales evaluation methods were weak. Much of the data the RTC used in evaluating SAMDA contract-driven disposition versus RTC-run auction sales came from the aforementioned problematic information systems. In fact, the RTC did not, at the time of the report, have a standard reporting schedule for its contractors, meaning that data like contracting fees, revenues, and expenses were not made available to the corporation because “some field offices [did] not require reporting until assets [were] sold” (GAO 1993a). Even certain key financial elements, such as operating income and expenses, were excluded from the RTC’s own analysis (GAO 1993a).FAdditional variables that were not included were property management expenses and litigation and foreclosure expenses. See GAO 1993a, 20, for more information.

Asset Dispositions. Finally, GAO’s report identified a conflict between one of RTC’s mandates and its asset disposition behavior. FIRREA statutes specifically stated that the RTC must maximize the net present value of the return of any asset disposition efforts (US Congress 1989, sec. 501). However, this requirement was called into question as the corporation appeared to be emphasizing balance sheet reduction. Four DC metro area regional auctions were used as an example of instances where RTC staff, “failed to provide potential buyers complete and accurate asset information, allow adequate time to evaluate assets, and properly prepare assets for sale. These planning and management inadequacies caused delays in closing, cancellations of contracts, and lower recoveries” (GAO 1993a). While put-option clauses would have, in theory, had the potential to alleviate some of these issues, their lengthy return window and high return rates meant that there were still valid concerns. These issues very clearly ran contrary to the RTC’s NPV maximization mandate, as well as the one that specifically mentioned minimizing the effects of asset disposition efforts on local real estate markets (US Congress 1989, sec. 501).

These concerns were also raised in Congress, as the RTC also obtained significant feedback from a number of businesspeople and policy experts such as Irvine Sprague, former chairman of the FDIC, Thomas Bennett Jr, executive vice president of Stillwater National Bank and Trust, and others (RTC Task Force 1990b). Much of their concern in 1989 and 1990 was that the corporation would be too quick to “dump” bad assets into distressed local real estate and financial markets (FDIC 1998). The desire to return assets quickly to local investors was prevalent as well, as the RTC was a massive player in many of these local markets despite being more of a liquidator than an active participant (RTC Task Force 1990b).

Certain publications, such as the Orange County Register, assailed the RTC about the practice of, in some cases, keeping executives of failed thrifts onboard and paid without any specific duties (RTC Task Force 1990b). The RTC’s annual reports had a section and data available that detailed the executive compensation schedules both pre- and postconservatorship, and the then–chairman of the corporation, William Seidman, made clear that any incidents of this nature were not intentional and would be rectified (RTC Task Force 1990b).

Additionally, the RTC Completion Act of 1993 put more stringent requirements on the RTC with respect to the disposition of larger assets. Post RTCCA, the corporation was required to assign management and disposition authority to a “qualified entity,” which would then “(1) analyze each asset and consider alternative disposition strategies, (2) develop a written management and disposition plan for the asset, and (3) implement this plan for a reasonable period of time . . .” (US Congress 1993).FThe RTC was required to undertake these additional steps for real property with a book value of greater than $400,000 and nonperforming real estate assets that had a book value of $1 million. See GAO 1995b, 11–12, for more information.

Lea and Thygerson (1994) developed a net present value-optimizing model of the RTC’s asset disposition efforts to determine the optimal method for selling various classes of assets (e.g., liquid versus illiquid). Because the pace of the RTC’s sales was quite slow initially, the corporation disposed of assets much more rapidly despite their objectives to maximize revenue and minimize disruption to markets (among others). The authors find that liquid assets and retail deposit franchises should have been sold as quickly as possible, while illiquid but performing assets were good candidates for securitization, and nonperforming illiquid assets were good candidates for equity partnerships. The authors also recommended that the RTC cease put-option sales, as they allowed buyers to be too selective. Adding a put fee, the authors stated, would not be viable either, as pricing the option would be complex.

Market Conditions. In addition to potential bidders being exceptionally wary of the assets of these distressed institutions, the RTC was also warned about “dumping“ huge amounts of distressed assets into local real estate markets (FDIC 1998). In many real estate markets, such as Oklahoma’s, the RTC was the largest financial institution and often owned the most real estate assets. This exacerbated the concern about the RTC liquidating its assets too soon, particularly if there weren’t enough buyers to satisfy demand. This was a common concern in the early days of the crisis as real estate values continued to plunge amidst the RTC’s disposition efforts. Some suggested that the RTC ought to break up its huge pools of performing loans into smaller ones so that local and community banks could purchase them (RTC Task Force 1990a). The RTC, in 1990, addressed these concerns by breaking up its asset pools and encouraging more regionally based sales and loan auctions so that smaller and more local bidders could more easily participate.

Despite these assertions that the RTC was too quick to sell assets and was engaging in “fire sale” practices, later analysis has suggested that the acquirers of thrifts or assets did not see dramatic bumps in their stock prices following the announcement of acquisition (Nanda, Owers, and Rogers 1997). The opposite effect, in some cases, has been found to be true, where institutions that were counterparties in whole-thrift P&A, mutual institution, and Western property transactions saw “persistently negative abnormal returns” (Nanda, Owers, and Rogers 1997).

The RTC’s pricing was further discussed by Nanda, Owers, and Rogers (1997), as some of its sales to publicly traded acquirers were given out at what some considered to be discounted prices and may have boosted their stock price performance. However, the authors find that there was no significant increase in the performance of winning bidders. Meta-analysis by Gupta and Misra (1999) find this relationship generally holds across the literature, with some caveats (summarized below). In some cases, the authors document small but negative announcement effects for some acquiring thrifts early in the crisis. Acquisitions facilitated by FSLIC prior to the establishment of the RTC, however, did produce significant positive returns for acquirers, potentially indicating that changes in resolution practices instituted by FIRREA reduced taxpayer costs. Finally, acquirers of thrifts resolved under the ARP experienced some slightly positive increases in performance, while non-ARP acquirers saw no performance increases.

Contracting Issues. As a new agency handling hundreds of billions of dollars in troubled asserts, the RTC heavily relied on outside contracting and private sector expertise, much more so than the FDIC, which was also resolving other troubled institutions at the time (FDIC 1998). While the RTC had a decentralized organizational structure with multiple regional and consolidated offices spread throughout the US, the organization was never staffed fully and was thus not able to be a proper administrator for these contractors. Any contractor whose annual fees amounted to more than $50,000 was required to undergo a background check, and five contractors in a sample of 30 of the RTC’s top 100 contractors had not done this (GAO 1993c).FThese contractors had average annual fees ranging from $6 million to $34 million each. Fees for subcontractors under SAMDA contracts, on average, were five times as much as the fees paid by the RTC to the SAMDA contractors themselves (FDIC 1998).

To alleviate some of these contracting concerns, the RTC created three new contracting compliance positions and adopted a Competition Advocate Program to ensure contractors were fairly competing against one another. However, at the time of the report, more than 25,000 contracts had already been issued, and only 13 people were given the task of monitoring both outstanding contracts and the dozens of new ones that were being created (GAO 1993a).

RTC Improvements. Many of the GAO’s reports were authored from 1991 to 1993, and thus gave the RTC multiple opportunities to manage its administrative, informational, and financial shortcomings more effectively. In total, GAO identified 21 major reforms that fit into four broad categories: (1) general management functions, (2) resolution and disposition activities, (3) contracting (including MWOBs) activities, and (4) Oversight Board reform (GAO 1995a, 22–23). In its final analysis of RTC’s progress on implementing these management reforms, GAO reported that, of the 21, only two were still works in progress, while the rest had either been completed or had had action taken (GAO 1995a).

Another GAO report, released in May 1995, suggested that the RTC had made significant improvements in several areas. GAO found that sales methods that involved the corporation maintaining a residual ownership role in the assets was vital to clearing its remaining inventory, much of which comprised hard-to-sell assets. Contract issuance decreased by 51% in the first six months of 1994 compared to the first six months of 1991, partially due to a diminishing asset portfolio as well as more stringent oversight. Assets under contractor management also decreased by 76%. Tighter internal controls—such as more robust auditing procedures and adopting data quality plans to obtain critical data elements for assets in its 17 major systems—were some of the ways the RTC tackled some of these criticisms (GAO 1995b). In light of these continued changes, the GAO removed the RTC from its high-risk list in its February 1995 High-Risk Series report (GAO 1995a).

Many of the RTC’s problems stemmed from inadequate predevelopment at the time of its inception and the monumental task of resolving a huge portion of a severely stressed savings and loan industry within a few short years. However, the corporation, spurred on by GAO recommendations and key pieces of legislation like RTCRRIA and RTCCA, was able to work toward, and make, improvements in several key areas.

The RTC also conducted an analysis of its disposition of hard-to-sell assets in 1992, as this had become a top priority for corporation leadership. The report reviewed the response of market participants to the RTC’s sales strategies, identified issues that were inhibiting the hard-to-sell asset disposition process, and analyzed the net returns to the corporation from certain disposition methods. The RTC ultimately had the following recommendations:

- Emphasize the sale of assets in portfolios rather than in individual asset transactions,

- Design product packages that were tailored to all markets,

- Sell products through both established and innovative sales strategies,

- Emphasize the importance of early and thorough due diligence, and

- Provide consistent and reliable postsettlement information for all sales strategies (GAO 1993d).

The RTC also found that using multiple sales strategies attracted a larger and more diverse group of potential buyers, thereby increasing competition and overall returns. The corporation’s analysis also showed that the range of projected net recoveries for SAMDA sales was lower than for direct sales and auctions. While the findings in this report were useful in providing additional guidance on future hard-to-sell disposition efforts, a GAO analysis of the report urged a cautious interpretation of some of the RTC’s data, as some of it—namely the data used to measure the results of its disposition strategies—was too incomplete and limited (GAO 1993d).

Selection Bias. In an analysis of the costs of FDIC resolutions and liquidations during the early years of crisis (1986–1991), Bennett and Unal (2014) find that, while FDIC resolutions appeared to have been more cost-efficient than liquidations, the characteristics of the banks that were being resolved or liquidated were a much more significant determinant of costs. Generally, banks that had greater franchise value and were healthier relative to others were selected for private sector reorganization, while less healthy ones were liquidated. When controlling for these aspects, they find that there were no cost differences between the two methods during this period. This is surprising, as “private-sector reorganizations include premium payments to the FDIC for the franchise value of the deposits they assume. However, in FDIC liquidations the franchise value is destroyed” (Bennett and Unal 2014). This finding is key because it implies that there were significantly higher inherent costs to the FDIC for private sector reorganization. However, liquidation was found to be less cost-effective even after controlling for institutional characteristics in the period of 1992–2007, one where significantly less stress was observed.

While the findings in this paper explicitly discusses FDIC resolutions during and after the S&L crisis, this same phenomenon may have affected cost estimates for RTC resolutions, as well. As discussed in earlier sections, P&As (and the ARP) appear to have been less costly, on average, but these figures do not take into account the financial condition of the thrift being resolved. For example, the reason the RTC sustained such heavy losses early in the crisis was not that the corporation chose to use deposit transfers and payoffs in lieu of P&As but that the thrifts that needed assistance early on were far worse off financially than those that failed later. This was especially true for the firms that were placed under conservatorship by FSLIC but were unable to be resolved due to its insolvency.

Costs to the Public. Even the total cost estimates of the crisis vary dramatically, as Curry and Shibut (2000) discuss. Initially, expected loss estimates hovered around $30 billion to $50 billion, but some nongovernment experts estimates are closer to $100 billion. The Bush Sr. administration estimated that approximately 400 thrifts with more than $200 billion in assets would need to be managed by the RTC, with estimated costs of about $50 billion. These initial estimates were the basis for the original funding level of the RTC.

The massive discrepancies between estimated and actual failures were due to several key factors, the authors write. First, the available data—especially during the earlier years—was either inaccurate or completely lacking. Thrift supervision had been lax and examinations infrequent. The data that was available was based on relaxed accounting standards that obscured the true financial conditions of many of the firms. Second, a changing economy made it very difficult to properly estimate the expected number of thrift failures. Because the design of the RTC was, in part, based on these expectations, the corporation was not prepared, and its leadership had little political capital to return to Congress and admit they made a big mistake (Curry and Shibut 2000). One may recall the tremendous difficulty in getting the RTC operational in the first place.

Third, the projections are subject to considerable methodological variance. Some estimates include both projected RTC losses as well as past FSLIC ones; while others include both but exclude losses sustained by the thrift industry, instead focusing only on taxpayer losses. Additionally, estimates sometimes include financing costs from the billions of dollars in debt instruments issued to fund the response. A total of $38.3 billion of FICO and REFCORP bonds were purchased by private investors, and an additional $99 billion was purchased by the government, which itself had to borrow funds (Curry and Shibut 2000). Some cost estimates include not just the amount borrowed but interest costs for up to 30 to 40 years for some or all of the debt issuances.

Including all of the costs of borrowing could very well double or triple cost estimates. For example, the GAO estimated that total interest expenses to taxpayers for FICO and REFCORP bonds would be $76.2 billion, and total estimated interest expenses for appropriations (i.e., Treasury borrowings) was about $209 billion (GAO 1996). The authors stated that adding interest payments to the amount borrowed would overstate costs, as, in present value terms, the amount borrowed is equal to the sum of interest payments and debt repayment. The federal government does add interest payments to the amount borrowed when calculating the taxpayer costs of other programs. These factors have caused cost estimates to vary widely, which makes it difficult to get a proper handle on the size and scope of both the crisis and what was needed to respond to it.

- Adams, Dirk S., Rodney R. Peck, and Jill W. Spencer. 1992. “Firrea and the New …

- Basle Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). 1988. “International Convergence…

- Bennett, Rosalind L., and Haluk Unal. 2014. “The Effects of Resolution Methods …

- Cull, Robert, Maria Soledad Martinez Peria, and Jeanne Verrier. 2018. “Bank Own…

- Curry, Timothy, and Lynn Shibut. 2000. “The Cost of the Savings and Loan Crisis…

- Davison, Lee. 2005. “Politics and Policy: The Creation of the Resolution Trust …

- ———. 2006a. “The Resolution Trust Corporation and Congress, 1989–1993. Part I: …

- ———. 2006b. “The Resolution Trust Corporation and Congress, 1989–1993. Part II:…

- Dowd, Maureen. 1989. “Bush Savings Plan Calls for Sharing the Cost Broadly; Big…

- Effros, Robert C., ed. 1997. Current Legal Issues Affecting Central Banks, Volu…

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). 1998. Managing the Crisis: The FD…

- ———. 2000. FDIC Banking Review 13, no. 2.

- ———. 2018. Managing the Crisis: The FDIC and RTC Experience–Chronological Overv…

- ———. 2019. “Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Resolutions Handbook.” Januar…

- Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). 2011. “FHFA Announces Completion of RefC…

- Federal Register (FR). 1989. “Department of the Treasury – Office of Thrift Sup…

- Garcia, Gillian. 2013. “Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982.” F…

- General Accounting Office (GAO). 1989. “The Budgetary Treatment of the Proposed…

- ———. 1991. “RTC: Financial Audit–Resolution Funding Corporation’s 1989 Financia…

- ———. 1992. “RTC: Asset Management Systems.” Report to the Resolution Trust Corp…

- ———. 1993a. “RTC: Funding, Organization, and Performance.” Testimony before the…

- ———. 1993b. “RTC: Status of Minority and Women Outreach and Contracting Program…

- ———. 1993c. “RTC: Better Assurance Needed That Contractors Meet Fitness and Int…

- ———. 1993d. “RTC: Data Limitations Impaired Analysis of Sales Methods.” Report …

- ———. 1995a. “RTC: Implementation of the Management Reforms in the RTC Completio…

- ———. 1995b. “RTC: Efforts Under Way to Address Management Weaknesses.” Report t…

- ———. 1996. “RTC: Financial Audit – Resolution Trust Corporation’s 1995 and 1994…

- Gupta, Atul, and Lalatendu Misra. 1999. “Failure and Failure Resolution in the …

- Lea, Michael, and Kenneth J. Thygerson. 1994. “A Model of the Asset Disposition…

- Moreland-Gunn, Penelope, Peter J. Elmer, and Timothy J. Curry. 1996. “Reps and …

- Moysich, Alane. 1997. “The Mutual Savings Bank Crisis.” In History of the Eight…

- Nanda, Sudhir, James E. Owers, and Ronald C. Rogers. 1997. “An Analysis of Reso…

- National Commission on Financial Institution Reform, Recovery and Enforcement (…

- Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC). 1991. “Annual Report of the Resolution Trus…

- ———. 1992. “Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1991.” June 30, 1…

- ———. 1995a. Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1994.” August 31,…

- ———. 1995b. Resolution Trust Corporation Statistical Abstract: August 1989/Sept…

- ———. 1996. “Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1995.” August 29,…

- Robinson, Kenneth J. 2013a. “Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary …

- ———. 2013b. “Savings and Loan Crisis: 1980-1989” Federal Reserve History, Novem…

- RTC Task Force. 1990a. “Disposition of Assets by the RTC.” Hearing before the S…

- ———. 1990b. “Semiannual Report and Appearance by the Oversight Board of the Res…

- ———. 1992. “Resolution Trust Corporation Refinancing and Restructuring Issues.”…

- Shorter, Gary. 2008. “The Resolution Trust Corporation: Historical Analysis.” C…

- US Congress. 1987. “Public Law No: 100-86–Competitive Equality and Banking Act …

- ———. 1989. “Public Law No: 101-73–Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and …

- ———. 1991a. “Public Law No: 102-18–Resolution Trust Corporation Funding Act of …

- ———. 1991b. “Public Law No: 102-233–Resolution Trust Corporation, Refinancing, …

- ———. 1993. “Public Law No: 103-204. 1993. “Resolution Trust Corporation Complet…

Key Program Documents

-

Managing the Crisis: The FDIC and RTC Experience 1980–1994 (FDIC 1998)

Detailed overview of both the RTC and FDIC’s responses to the savings and loan crisis. Chronology and breakdown of methods.

-

Managing the Crisis: The FDIC and RTC Experience–Chronological Overview (FDIC 2018)

FDIC overview of the savings and loan crisis broken down by year with significant events and statistics. Goes far beyond just 1989–1995. Chapters 12–18 cover those years, however.

-

Public Law No: 101-73 (US Congress 1989)

Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989. The legislation that created the RTC.

-

Resolution Trust Corporation Statistical Abstract: August 1989/September 1995 (RTC 1995b)

Document presenting historical time series data from 1989 through September 1995, including resolution listings by state and institution.

-

Public Law No: 101-73 (US Congress 1989)

Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989. The legislation that created the RTC.

-

Public Law No: 102-18 (US Congress 1991a)

Resolution Trust Corporation Funding Act of 1991. Gave the RTC an additional $30 billion in funding.

-

Public Law No: 102-233 (US Congress 1991b)

Resolution Trust Corporation, Refinancing, Restructuring, and Improvement Act of 1991. Gave the RTC an additional $25 billion in funding and implemented broad oversight reforms for the institution.

-

Public Law No: 103-204 (US Congress 1993

Resolution Trust Corporation Completion Act 1993. Authorized the expired appropriation from the RTCRRIA of 1991 and moved the closing date of the RTC up by a year.

-

Strategic Plan for the Resolution Trust Corporation (December 31, 1989)

Draft of the RTC’s strategic plan, submitted to Congress as per its FIRREA mandate. Contains implementation procedures, comments, and policy discussion about various methods of disposition and resolution.

-

Appendix A: Enforcement Actions – Section 080 (July 2008)

A set of prompt corrective actions set forth by the OTS regulating the operation of undercapitalized associations. This version has since been rescinded.

-

Effectiveness of RTC Regulations after RTC Termination (December 22, 1995)

A final rule drafted by the FDIC and RTC that elaborates on the status of current programs subsequent to the RTC’s dissolution. Only the Affordable Housing Disposition Program would continue to be active.

-

FDIC Resolutions Handbook (FDIC 2019)

A detailed description of the FDIC’s experiences resolving failed institutions, including lessons learned and historical resolution alternatives.

-

FDIC Risk Management Manual of Examination Policies – Sec. 3.6 – Other Real Estate (2012)

An official manual published by the FDIC that details the operational and regulatory treatment of ‘Other Real Estate’ held by banks.

-

Federal Register Vol. 54, no. 215 (FR 1989)

Government document published daily providing a uniform system for publicizing regulations and legal notices issued by federal agencies.

-

Public Law No: 100-86 (US Congress 1987)

Competitive Equality and Banking Act of 1987. This legislation created the Financing Corporation (FICO), helped regulate nonbanks financial institutions, allowed emergency interstate banking acquisitions, and more.

-

Bush Savings Plan Calls for Sharing the Cost Broadly; Big Sale of Bonds

A New York Times article announcing the Bush administration’s 1989 rescue plan to restore the deposit insurance system and, in particular, the savings and loan industry.

-

An Analysis of Resolution Trust Corporation Transactions: Auction Market Process and Pricing (Nanda, Owers, and Rogers 1997)

An academic paper published in Real Estate Economics that argues winning bidders rarely benefited from stock price gains when acquiring assets from the RTC.

-

The Cost of the Savings and Loan Crisis: Truth and Consequences (Curry and Shibut 2000)

FDIC Banking Review paper that provides a cost breakdown of both the now-defunct FSLIC and the RTC over the course of the S&L crisis. Examines the cost to taxpayers and the private sector.

-

The Effects of Resolution Methods and Industry Stress on the Loss on Assets from Bank Failures (Bennett and Unal 2014)

Academic paper examining the costs of resolving bank failures and comparing those involved in FDIC liquidations versus private sector resolutions.

-

Failure and Failure Resolution in the US Thrift and Banking Industries (Gupta and Misra 1999)

Academic paper surveying recent academic and regulatory case studies on the causes of the S&L crisis of the 1980s and 1990s.

-

Firrea and the New Federal Home Loan Bank System (Adams, Peck, and Spencer 1992)

A law review article examining the impact of FIRREA on the banking system, with particular focus on modifications made to corporate governance.

-

A Model of the Asset Disposition Decision of the RTC (Lea and Thygerson 1994)

Research paper analyzing the development of asset disposition models for the RTC.

-

Reps and Warranties (Moreland-Gunn, Elmer, and Curry 1996)

An article published by the FDIC that analyzes the RTC’s claims and experience with R&Ws.

-

Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1989 (RTC 1991)

The RTC’s annual report from 1989. Contains detailed financial statements and breakdowns on each division of the corporation.

-

Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1990 (October 15, 1991)

The RTC’s annual report from 1990. Contains detailed financial statements and breakdowns on each division of the corporation.

-

Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1991 (RTC 1992)

The RTC’s annual report from 1991. Contains detailed financial statements and breakdowns on each division of the corporation.

-

Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1992 (October 29, 1993)

The RTC’s annual report from 1992. Contains detailed financial statements and breakdowns on each division of the corporation.

-

Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1993 (September 30, 1994)

The RTC’s annual report from 1993. Contains detailed financial statements and breakdowns on each division of the corporation.

-

Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1994 (RTC 1995)

The RTC’s annual report from 1994. Contains detailed financial statements and breakdowns on each division of the corporation.

-

Annual Report of the Resolution Trust Corporation–1995 (RTC 1996)

The RTC’s annual report from 1995. Contains detailed financial statements and breakdowns on each division of the corporation.

-

The Cost of the Savings and Loan Crisis: Truth and Consequences (Curry and Shibut 2000)

FDIC Banking Review paper that provides a cost breakdown of both the now-defunct FSLIC and the RTC over the course of the S&L crisis. Examines the cost to taxpayers and the private sector.

-

Disposition of Assets by the RTC (RTC Task Force 1990a)

Testimony presented to Congress on the RTC’s plan for the continued disposition of assets.

-

FDIC Banking Review, Volume 13, No. 2 (FDIC 2000)

A retrospective collection of essays by on the history of—and lessons learned from—the FDIC’s experience dealing with the S&L crisis.

-

FDIC Resolution Tasks and Approaches: A Comparison of the 1980 to 1994 and 2008 to 2013 Crises (July 2020)

Report comparing and assessing FDIC-insured banks’ failures and the FDIC’s response during each crisis.

-

Lessons Learned: Obtaining Value from Federal Asset Sales (March 2003)

Research paper analyzing four case studies during which the government had valued assets, including the RTC.

-

The Mutual Savings Bank Crisis (Moysich 1997)

A chapter from History of the Eighties: Lessons for the Future. Vol. 1, An Examination of the Banking Crises of the 1980s and Early 1990s that details the S&L debacle and its relationship with other banking crises of the decade.

-

Origins and Causes of the S&L Debacle: A Blueprint for Reform (NCFIRRE 1993)

A report to the president and Congress of the United States detailing a blueprint of recommendations for financial reforms in the wake of the S&L crisis.

-