Bank Debt Guarantee Programs

The United States’ Debt Guarantee Program of the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program

Purpose

To ease stress and restore confidence and liquidity in U.S. interbank lending and promote access to unsecured funding markets for banks and other financial institutions.

Key Terms

-

Announcement DateOctober 14, 2008

-

Operational DateOctober 14, 2008

-

Date of First Guaranteed Debt IssuanceOctober 14, 2008

-

Issuance Window Expiration DateJune 30, 2009, (initial) then amended to October 31, 2009

-

Program SizeNo explicit cap

-

Usage122 participating institutions – $618 billion in guaranteed debt

-

OutcomesSix defaults totaling $153 million; $10.4 billion in fees

-

Notable FeaturesOpt-out structure with automatic enrollment

Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September of 2008, banks faced extreme difficulty in issuing new debt and finding affordable sources of funds due to heightened fears over counterparty solvency and liquidity risk. By the end of September, the TED spread had spiked to 464 basis points, and issuance of commercial paper fell 88%. On October 14th, to boost confidence and lower short-term financing costs, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation announced the Debt Guarantee Program (DGP) as part of the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (TLGP). Under the DGP, the FDIC guaranteed in full a limited amount of senior unsecured debt newly issued by insured depository institutions and certain bank holding companies that did not opt out of the program. Other affiliates of insured depositories were also able to apply to the FDIC for eligibility on a case-by-case basis. If an institution defaulted on a guaranteed bond, the FDIC would cover all payments on interest and principal. In exchange for receiving the guarantee, institutions paid a fee based on the bond’s maturity. The issuance window was set to expire on June 30, 2009, but was extended to October 31, 2009. An additional Emergency Guarantee facility, created at the time of extension, had an issuance window that expired on April 30, 2010, but was never used. Over the course of the program, the 122 participating institutions raised over $600 billion in guaranteed debt. The FDIC paid out about $153 million due to defaults from six institutions, and collected $10.2 billion in fees.

In the wake of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy and the failures of AIG, Washington Mutual, and Wachovia in mid-September 2008, interbank lending had all but frozen. As a result, by early October, even the most solvent institutions found it difficult to roll over their short-term obligations and access long-term financing.

To restart interbank lending and promote stability in the unsecured funding market for banks and other financial institutions, the FDIC announced the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program’s Debt Guarantee Program (DGP) on October 14, 2008, as part of a coordinated effort, along with the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department, to “bolster public confidence in […] financial institutions and throughout the American economy.” DGP extended an FDIC-backed guarantee, for up to approximately three years, to certain senior unsecured debt newly issued by program participants between October 14, 2008 and June 30, 2009. Under the DGP, insured depository institutions and certain bank holding companies that did not opt out of the program were eligible to participate. Other affiliates of insured depositories were also able to apply for eligibility.

To ensure an orderly transition, the FDIC extended the program twice. First, the FDIC extended the issuance window to October 31, 2009, and the guarantee to December 31, 2012. Second, the FDIC established a six-month Emergency Guarantee Facility to cover debt issued between October 31, 2009, and April 30, 2010, but this was never used. When the guarantee expired on December 31, 2012, the FDIC had collected $10.4 billion in fees and paid out $153 million due to defaults by six institutions.

It is difficult to determine whether the DGP directly caused the observed changes in credit markets since two additional programs, the Treasury’s Capital Purchase Program and the Federal Reserve’s Commercial Paper Funding Facility, were announced around the same time as the DGP. However, there is overall consensus that the DGP lowered borrowing costs for banks and improved liquidity in unsecured funding markets for banks and other financial institutions.

Key Design Decisions

Related Programs

1

In addition to the DGP, the TLGP had a second component called the Transaction Account Guarantee Program that provided a blanket guarantee on non-interest-bearing transaction accounts at participating banks and thrifts. These transaction accounts were of the type commonly used to meet payroll and other business purposes. The TAGP sought to prevent a run on such accounts by providing them with a full guarantee. At introduction the TAGP was designed to last until December 31, 2009, but the FDIC subsequently extended this termination date to December 31, 2010.

U.S. policymakers also introduced (or first explained) two additional programs on October 14th that were seen as linked to the DGP. The Capital Purchase Program (CPP) announced by Treasury at the same press conference as the TLGP provided up to $250 billion for capital injections into viable financial institutions. Authorities informed the nine major financial institutions that were the initial recipients of capital injections pursuant to the CPP that participation in the CPP was a requirement for accessing the DGP. This was both (a) so that the institutions would have larger capital buffers and thus be less likely to impose losses on the DGP by defaulting on guaranteed debt and (b) to avoid the stigma that might result from certain major financial institutions participating in the DGP while others declined to do so. No other institutions were explicitly required to accept capital via the CPP in order to participate in the DGP, but the two programs were generally seen as complementary.

On October 14, the Federal Reserve Board also provided details of the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) it had enacted on October 7. Under the CPFF, a specially created limited liability company would use funds borrowed from the Federal Reserve Board of New York to purchase eligible commercial paper directly from issuers. This was intended to provide liquidity to commercial paper issuers otherwise unable to access it due to strains in the commercial paper market.

Legal Authority

1

The FDIC established the TLGP (and thus the DGP) under the authority of the FDIC Improvement Act of 1991 (FDICIA). Enacted in the wake of a series of thrift failures in the late 1980s and early 1990s that left the FDIC’s insurance fund seriously undercapitalized, the FDICIA required “least-cost resolution,” meaning that the FDIC had to select a method of providing assistance to troubled insured depository institutions that would minimize the cost to the Deposit Insurance Fund. However, the law included a “systemic risk” exception that authorized the FDIC to bypass the least-cost resolution requirement if following it “would have serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability” and overlooking it “would avoid or mitigate such adverse effects.” In the event of any loss to the Deposit Insurance Fund stemming from an action undertaken based on the systemic risk exception, the law requires the FDIC to recover that loss through “1 or more special assessments on insured depository institutions, depository institution holding companies (with the concurrence of the Secretary of the Treasury with respect to holding companies), or both, as the [FDIC] determines to be appropriate.”F12 U.S.C. 1823(c)(4)(G)

On October 13, 2008, the Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the President, invoked the systemic risk exception to facilitate the TLGP based on the recommendations of at least two-thirds of the FDIC’s Board of Directors and two-thirds of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, all as required by law.FAfter the crisis, the FDIC’s use of the systemic risk exception to enact a widely available guarantee program came under significant legal scrutiny, and the Dodd-Frank Act curtailed the FDIC’s authority to introduce a program like the DGP.

Program Size

1

Program documents did not contain any mention of a limit on the amount of guaranteed debt that could be issued under the DGP.

Eligible Institutions

2

While the FDIC was working with the Treasury and Federal Reserve on the development of the DGP, an initial difference of opinion existed on the range of institutions that should be eligible for the program. The FDIC, whose historical mandate and experience revolved around the protection of insured depository institutions, sought to limit the program to such institutions. The Treasury and Federal Reserve argued for the inclusion of a broad range of nonbank financial institutions. Ultimately, those eligible for the DGP included insured depository institutions and bank and financial holding companies. The inclusion of holding companies stemmed from the observation that the senior unsecured debt covered by the DGP was typically issued at the holding company level in most holding company structures, with the holding companies then providing liquidity to their depository institution subsidiaries. (Federal Register 73 [229]: 72244 and 72250, 2008)

The DGP also allowed for the participation of other affiliates of insured depository institutions, provided that such affiliates would be admitted on a case-by-case basis in the sole discretion of the FDIC based on “such factors as (1) the extent of the financial activity of the entities within the holding company structure; (2) the strength, from a ratings perspective, of the issuer of the obligations that will be guaranteed; and (3) the size and extent of the activities of the organization” (Ibid.).

The rules implementing the DGP enabled the FDIC, working with the other federal regulators, to monitor and limit use of the facility by weaker institutions. In particular, institutions with the lowest supervisory ratings were barred from participating.

The FDIC designed the DGP’s enrollment structure to convince as many eligible institutions as possible to participate, regardless of their credit risk (Technical Briefing on the TLGP 2, 2008). The FDIC believed that automatic enrollment and an opt-out structure would normalize program participation, encourage stable banks to issue guaranteed debt, and collect sufficient fees to cover potential program losses. Moreover, the FDIC played on institutions’ risk aversion by not allowing them to rejoin the program later if they opted out by the December 5 deadline (initially November 12, but later extended). Some institutions without financing problems in October and November still chose to participate, since they worried they would suffer unexpected illiquidity in the future.

Officials wanted to maximize participation in the program for two reasons. First, they believed that strained access to credit was widespread, so many firms would have to participate to meaningfully calm markets. Second, they wanted to minimize adverse selection, where firms most likely to default would be the only ones participating. If the market viewed participation as a signal that a firm was insolvent, then the DGP would not cut borrowing costs for solvent firms with liquidity problems. Additionally, if only troubled firms participated, then the FDIC would have to either (1) suffer massive losses as a result of the program; or (2) increase participation fees, which would only exacerbate adverse selection and increase borrowing costs further (GAO, 2009).

The one exception to the DGP’s opt-out structure were the insured depository institution-affiliates discussed above, who had to apply to the FDIC to participate.

Eligible Debt - Type

1

The purpose of the DGP was to promote liquidity and stability in interbank unsecured lending markets. To do so, regulators believed it best to only guarantee senior debt.

The DGP specifically excluded unsecured debt with embedded instruments for two reasons. First, the FDIC wanted to promote stability, confidence, and transparency in securities markets, but “not to encourage innovative, exotic or complex funding structures” (Federal Register 73 [229]: 72245, 2008). Second, officials worried that weak banks would use derivatives to obscure underlying risk (Federal Register 73 [229]: 72252, 2008). As such, extending guarantees to those instruments could expose the FDIC to additional risk without meaningfully improving liquidity.

When Treasury Secretary Paulson and Federal Reserve Chair Bernanke approached the FDIC Chair Shelia Bair about guaranteeing bank debt, Bair was reluctant to proceed. She worried that the program would potentially expose the FDIC to huge losses and questioned how such a guarantee program fulfilled the FDIC’s depositor protection role. However, recognizing the risks of a prolonged liquidity crisis, she proposed a program that would guarantee 90% of newly-issued senior unsecured debt. Paulson and Bernanke insisted that a 90% guarantee would not be sufficient to calm markets, and Bair compromised on a program that would cover 100% of certain debt, but only within a limited time frame (Bair, 2011).

Eligible Debt - Maturities

1

Initially, debt of any maturity could be issued pursuant to the DGP. The guarantee on such debt would then last until maturity or June 30, 2012 (whichever came first). Subsequent amendments later altered this approach.

First, the Final Rule issued on November 21, 2008, excluded debt with maturities of 30 days or less. The FDIC observed that, while other federal programs had improved liquidity in short-term funding markets, institutions still struggled to access longer-term unsecured funding. Thus, the DGP would “help institutions to obtain stable, longer-term sources of funding where liquidity is currently most lacking” by focusing on maturities of more than thirty days (Federal Register 73 [229]: 72251, 2008).

Second, an amendment to the DGP adopted on June 3, 2009, extended the life of the guarantee to December 31, 2012, for debt issued on or after April 1, 2009. The FDIC adopted this extension of the guarantee alongside an extension of the issuance window for guaranteed debt from June 30, 2009, to October 31, 2009, as described in more detail below.

During the life of the DGP, some market participants suggested that the FDIC extend the guarantee to as long as ten years given that “real money investors” such as pension funds and insurance companies were more active in longer-term markets. However, the FDIC rejected these suggestions, arguing that extending guarantees to longer-term debt would not be necessary to improve liquidity to interbank and unsecured term debt markets (Federal Register 73 [229]: 72253, 2008).

Eligible Debt - Currencies

1

Program documents did not contain any language restricting the currencies that were eligible for the DGP.

Participation Limits for Individual Firms

1

In order to ensure that the DGP was used to rollover existing debt rather than significantly expand debt issuance, the FDIC imposed a cap on the amount of guaranteed debt that a participating institution could issue. The FDIC set this cap at 125% of senior unsecured debt outstanding on September 30, 2008, that would mature by June 30, 2009.

Initially, institutions with no senior unsecured debt outstanding on September 30, 2008, could apply to the FDIC for eligibility to issue an amount of debt to be determined by the FDIC. However, concerns that such an approach might delay determinations of eligibility amounts resulted in the exploration of other options. In the Final Rule issued on November 21, 2008, the FDIC established a cap equal to 2% of consolidated total liabilities as of September 30, 2008, for institutions with no senior unsecured debt outstanding. For all participating institutions, the FDIC could increase or decrease these caps should it deem it necessary after consultation with the appropriate federal banking agency.

These caps were particularly significant because, with one exception noted below, participating institutions were not permitted to issue non-guaranteed debt until the caps were reached. Eligible institutions strongly opposed this measure. Critics made numerous arguments in favor of allowing any institution to issue non-guaranteed debt at will before hitting the cap, including that a prohibition on non-guaranteed issuance would limit flexibility, cause healthy banks to avoid the program, and result in a competitive disadvantage relative to the UK’s Credit Guarantee Scheme (Federal Register 73 [229]: 72255-6, 2008).

Despite these concerns, the FDIC decided to maintain the prohibition on non-guaranteed issuance under the cap for several stated reasons. The “[f]irst, and most important” reason the FDIC retained the rule was to avoid adverse selection, where banks only sought to have guaranteed the debt that they were least likely to repay. On a more pragmatic note, the FDIC worried that widespread issuance of non-guaranteed debt under the cap would lead to confusion about what bonds received the guarantee, while the existing structure would calm markets through consistency (Federal Register 73 [229]: 72255-6, 2008).

The one exception to the prohibition on non-guaranteed issuance was for institutions that affirmatively made an election by a specified date to have the right to issue non-guaranteed debt under the cap and paid a fee for the right equal to 37.5 basis points times the amount of unsecured debt outstanding as of September 30, 2008, maturing by June 30, 2009. Such institutions could issue non-guaranteed debt with maturities greater than June 30, 2012, at any time.

The FDIC also barred banks from using the proceeds from guaranteed debt to prepay debt that was not guaranteed.

Fees

1

Initially, the FDIC charged a flat annualized rate of 75 basis points on all guaranteed debt, a weighted average of CDS spreads in 2007 (before the subprime crisis hit) and September 2008 (when spreads reached several hundred basis points). The 75-basis-point figure represented the sentiment that by late 2008, default risk was higher than usual but lower than during the height of the crisis (Technical Briefing on the TLGP 1, 2008).

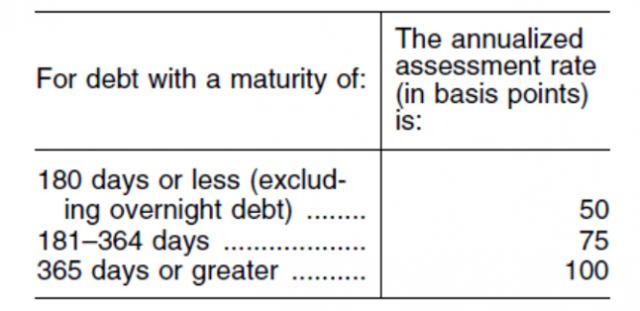

However, the 75-basis-point fee proved prohibitively high for short-term borrowing, with institutions reliant on short-term credit threatening to opt out of the program entirely. In response, in the Final Rule adopted November 21, 2008, the FDIC introduced a range from 50 basis points to 100 basis points based on maturity as follows:

Figure 3: DGP Fee Scale

Source: Federal Register 73(229): 72251, 2008.

Source: Federal Register 73(229): 72251, 2008.

This range was increased with the June 3, 2009, amendment to the DGP extending its issuance window and guarantee. For debt issued on or after April 1, 2009, surcharges of 25 basis points (for insured depositories) or 50 basis points (for other participants) would be applied. For any debt issued pursuant to the Emergency Guarantee Facility, a minimum annualized fee of 300 basis points would apply.

The FDIC considered adopting a fee structure where institutions with a higher credit risk paid higher premiums. Such an approach ensures riskier firms bear higher costs for participating in the program, maintaining market discipline. However, officials said they opted against this approach for practical reasons. The FDIC did not have the time to properly assess differential risk among banks. In addition, the FDIC lacked the regulatory infrastructure and statutory authority to assess the riskiness of bank holding companies and nonbank financial institutions, which, as non-insured institutions, did not fall under the FDIC’s jurisdiction (COP 2009).

Officials at the Federal Reserve urged the FDIC to include bank holding companies and thrifts in the guarantee program as a crucial way to restore liquidity. However, including holding companies and thrifts initially introduced a legal challenge. In the event that program losses exceeded fees, the FDIC had planned to make use of its “special assessment” authority to collect a special fee from all institutions with federal deposit insurance. Bank holding companies and thrifts were not FDIC-insured, meaning the FDIC did not have the statutory authority to impose additional fees on them. To compensate for the fact that they would not be liable in the event of program losses, the FDIC decided to raise the standard assessment fee by 10 basis points on holding companies where FDIC-insured institutions consisted of less than half of the firm’s portfolio (Federal Register 73 [229]: 72251, 2008).

Recognizing this legal challenge, Congress amended FDICIA to allow the FDIC to collect special assessments on depository institution holding companies in May 2009 as part of the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act (GAO, 2010).

Other Conditions

1

The CPP imposed several conditions on participating institutions, including restrictions on executive compensation and a prohibition on increasing dividends. These conditions were not adopted for the DGP.

Process for Exercising Guarantee

1

Initially, the FDIC said it would only fulfill the guarantee if the debtor declared bankruptcy/entered resolution, at which point the FDIC would pay the creditor the remaining balance plus interest and require the creditor to turn over all claims to the debtor’s assets to the FDIC. However, some worried that this approach would prevent the timely exercise of the guarantee and curtail demand for guaranteed debt. In particular, ratings agencies indicated an unwillingness to treat guaranteed debt as government securities (and therefore AAA rated) unless payment was made on default. Thus, if guarantee payments were not delivered in a timely manner, then only the largest institutions deemed already creditworthy would be able to access interbank lending markets, locking out smaller firms without credit ratings. Additionally, since the UK’s Credit Guarantee Scheme paid creditors following the first default on payment, participants worried that UK banks would receive a competitive advantage over U.S. ones (Federal Register 73 [229]: 72263, 2008). For these reasons, the FDIC changed the DGP such that the first payment default on covered debt would trigger the guarantee.

Program Issuance Window

1

In spring 2009, the FDIC believed that liquidity in financial markets had not returned to pre-crisis levels and worried that an abrupt end to the DGP would lead to market disruption. To ensure an orderly termination of the DGP, officials designed the program’s phase-out to make it slowly uneconomical to issue guaranteed debt (Treasury, 2009). The first extension, from April 1, 2009, to October 31, 2009, raised the participation fee by 25 basis points for FDIC-insured institutions and 50 basis points for holding companies and thrifts. Eligible institutions that had not issued guaranteed debt by that date had to apply for inclusion in the program to prevent program participation from ballooning. All fees collected under the extension were directly deposited into the Deposit Insurance Fund to shore up the FDIC’s balance sheet. The FDIC guaranteed debt issued under the extension through December 31, 2012 (Federal Register 74(105), 2009).

By October, the FDIC recognized that certain firms, due to exogenous market disruptions or other factors beyond their control, found it difficult to roll over their guaranteed debt. Therefore, officials established the Emergency Guarantee Facility to guarantee debt issued between October 31, 2009, and April 30, 2010. Institutions had to apply with the FDIC to issue guaranteed debt until April 30, 2010. The FDIC charged a participation fee of at least 300 basis points, and only firms that previously issued DGP-guaranteed debt were allowed to apply (to limit participation). The FDIC designed the extension to maximize regulatory discretion. All institutions approved to participate in the emergency facility had to be in some extreme, unique circumstance, so FDIC granted regulators the authority to carefully tailor participation requirements on a case-by-case basis (Federal Register 74 [204], 2009). Ultimately, no institutions made use of the Emergency Guarantee Facility.

Economic Consequences

There is overall consensus that the DGP lowered borrowing costs for banks and improved liquidity in unsecured interbank markets. Although the near-simultaneous announcement of other liquidity-boosting measures like the Treasury Department’s CPP and the Fed’s CPFF makes it seem difficult to isolate the individual effect of the DGP on overall credit markets, comparing guaranteed debt to non-guaranteed debt issued by the same institutions provides a means to evaluate the program’s effects.

In its report on the DGP, the Congressional Oversight Panel (2009) measured the DGP’s effect on interest rates using two methods, one that computed the average interest rate spread between guaranteed and non-guaranteed debt issued during the program period by the same institution, and one that examined average difference in yield between guaranteed debt and debt trading on secondary markets that was issued before October 2008. The Panel estimated that the DGP lowered borrowing costs by between about 150-300 basis points, for total savings of between $13.4 billion and $28.9 billion (COP, 2009). Those estimates indicate that the program resulted in a net subsidy for banks, since participating institutions only paid $10.4 billion in fees. This methodology is limited by the fact that many issuers of guaranteed bonds did not simultaneously issue debt without the guarantee, since total issues did not exceed the 125% cap. Using a multivariate regression framework to control for other factors influencing bond yields, Ambrose et al (2013) found that FDIC-backed debt cost 132 basis points less than non-FDIC-backed debt, a slightly lower benefit for banks that more closely aligns with the fees paid (Ambrose et al, 2013).

Using a similar methodology to Ambrose et al, Black et al (2015) found an average reduction in borrowing costs similar in magnitude to Ambrose’s estimate. However, the study also found a significant effect of bond maturity on the benefit to banks. The benefit decreased with maturity, such that the guarantee lowered borrowing costs more for short-term bonds than for long-term bonds (Black et al, 2015). This result seems to run counter to the program’s goal of encouraging medium-to-long-term borrowing. However, given that the lion’s share of bonds issued under DGP had maturities of over a year, those apparently misaligned incentives may not have outweighed other considerations affecting the term on debt issues. It is also possible that the larger benefit for short-term bonds merely reflected that prevailing market rates for short-term debt were more disrupted by market conditions than for long-term debt in 2008-09.

In addition to lowering borrowing costs, both Black and Ambrose found that the DGP improved bank liquidity. As a result, banks were able to meet their rollover and medium-term financing needs, reducing their default risk. However, Ambrose argues that announcement of DGP participation signaled a bank’s weakness, offsetting greater confidence in bank solvency and resulting in a net decline in share price (Ambrose 2013). Black disagrees, and finds that, while share prices did continue to slide after institutions announced they would participate, the rate of decline slowed for participating institutions relative to non-participants (Black 2015).

By reducing the risk of bank failure and improving market liquidity, the DGP produced spillover benefits both for participating institutions and the unsecured debt market as a whole. Black et al measured higher liquidity for non-guaranteed bonds issued by banks participating in the program (Black 2015). Ambrose et al found that participating institutions enjoyed lower borrowing costs on non-guaranteed debt, while all banks, regardless of whether or not they issued guaranteed bonds, enjoyed lower spreads (Ambrose et al, 2013).

Although fees collected under the program significantly exceeded payouts, some argue that there were several types of costs associated with the program. Veronesi and Zingales (2009) multiply the total amount of guaranteed debt issued by the CDS rates at participating institutions, subtract revenue from fees collected, and arrive at an expected net cost of about $11 billion over three years (Veronesi and Zingales 2009).

The program may have led to other indirect costs as well. Hoelscher et al (2013) estimated that firms with weaker credit ratings received a greater benefit under the program, suggesting that the DGP subsidized riskier firms with more reckless credit management. In doing so, the guarantee program may have facilitated risky behavior and created market distortions by allocating resources to banks that use them inefficiently. Additionally, the Government Accountability Office warned that the guarantee program weakened the incentive for creditors to monitor risk-taking and restrict lending to irresponsible banks. The DGP may have contributed to a moral hazard problem by creating the perception that the government would intervene in the future to solve liquidity problems (GAO, 2010).

Overall, the DGP is seen as helping restore confidence in interbank lending markets. The GAO concluded in its report that to the extent that DGP “helped banking organizations to raise funds during a very difficult period and to do so at substantially lower cost than would otherwise be available, it may have helped improve confidence in institutions and their ability to lend” (GAO, 2010).

Legal Dispute

The FDIC enacted the DGP under the authority of the FDICIA, which required the FDIC to use the least costly method of resolving troubled financial institutions unless doing so would cause systemic risk. Once two-thirds of the FDIC’s Board of Directors, two-thirds of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, and the Treasury Secretary in consultation with the President made a systemic risk determination, the FDIC was authorized to “take other action or provide assistance” to mitigate adverse economic effects. In October 2008, the FDIC (in consultation with relevant authorities) made a systemic risk determination and created the DGP under its authority to “take other action” to restore financial stability. That interpretation raised numerous legal concerns (GAO 2010). First, the statute states that a systemic risk determination can only be made when the FDIC’s least-cost compliance “with respect to an insured depository institution” would cause adverse economic conditions, suggesting that the exception only applies when least-cost FDIC assistance to a specific institution would cause adverse economic conditions. By contrast, to establish the DGP, the FDIC made a “generic systemic risk determination […] generically for all institutions” with respect to the “US banking system in general.” Second, the statute suggested that the FDIC only had the authority to extend special assistance to institutions with specific problems, not, as under the DGP, to all institutions involved in a problem affecting the banking system as a whole. Third, the systemic risk exception was structured to waive only the least-cost restrictions, meaning that “other action” was still subject to the general restraints on FDIC assistance that expressly prohibit many DGP provisions. Fourth, precedent set by previous systemic risk determinations made by the FDIC suggested a more restrictive reading of the statute, since officials only authorized unconventional assistance to individual institutions if, individually, they were systemically important. Finally, the FDICIA’s history suggests that Congress did not intend to grant the FDIC broad authority to enact programs like DGP. The least-cost resolution was enacted to constrain the FDIC’s resolution authority; the systemic risk exception replaced a more permissive exemption under the original Federal Deposit Insurance Act.

In the face of those criticisms, the FDIC justified its authority to enact DGP by pointing to ambiguities in the statute that suggested their authority to take broader actions in the face of systemic risk. First, the FDIC argued the exception allows a generic determination, since U.S. code allows the phrase “with respect to an insured depository institution” to be read as “with respect to one or more institutions.” Second, the FDIC interpreted FDICIA’s authorization to “take other action or provide assistance under this section” as permitting two types of activities: first, to “provide assistance under this section,” subject to the general restrictions on FDIC assistance; and second, to “take other action,” not subject to the restrictions “under this section.” Under this interpretation, DGP constituted “other action” not subject to the traditional restrictions on assistance to insured depository institutions. To justify this reading, the FDIC: (1) argued the conjunction “or” suggested differentiation between two different types of activity; and (2) cited the statutory construction principle called the “grammatical rule of the last antecedent” which calls for “under this section” to be read as only modifying “provide assistance,” not “take other action.” Third, including the systemic risk exception indicated that Congress intended to allow the FDIC to take action aimed at preventing the overall failure of the financial system. Thus, in an unexpected circumstance like the 2008 financial crisis, the statute authorizes the FDIC to provide generic assistance to members of the banking industry to facilitate financial stability. Fourth, the FDIC pointed to Congress’ May 2009 amendment to the FDICIA allowing special assessments on bank holding companies as evidence that legislators tacitly endorsed the DGP. Finally, the FDIC noted that historically, in the face of statutory ambiguities, the Supreme Court has urged substantial deference to agencies’ interpretations (GAO, 2010).

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank) eliminated the FDIC’s ability to create a widely available guarantee program like DGP without explicit Congressional approval under the systemic risk exception. However, under certain circumstances, Dodd-Frank authorizes the FDIC to establish a program to guarantee obligations of solvent insured depository institutions and holding companies. First, if two-thirds of the FDIC’s Board of Directors, two-thirds of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, and the Treasury Secretary determine that there are “broad and exceptional” reductions in asset resale values or “unusual and significant” inabilities of financial institutions to sell unsecured debt, the FDIC can declare that a “liquidity event” exists that warrants the use of a guarantee program. Then, the FDIC, in consultation with the Treasury Department and following presidential recommendation, can propose a specific debt guarantee program to Congress, including a limit on the maximum amount of debt that the program will cover. Following congressional authorization, the FDIC may initiate the program. In the event that a participating institution defaults on guaranteed debt, the FDIC must place the institution in receivership. Dodd-Frank also allows the FDIC to guarantee an individual institution’s unsecured debt after placing it in receivership (12 USC Section 5611-12).

The total amount of debt that could potentially be guaranteed by the DGP’s, and thus, could be subject to losses was about $1.75 trillion (Black et al, 2015). The sweeping range of the program motivated Dodd-Frank’s restriction of the FDIC’s ability to enact broad guarantee programs. Legislators believed that regulators should not have the authority to subject taxpayers to trillions of dollars of risk without congressional approval. Additionally, by making explicit the requirement that the FDIC only cover debt for solvent institutions, Dodd-Frank aimed to limit moral hazard associated with future guarantee programs (111-176 U.S. Senate, 2010). While in theory requiring congressional approval provides a prudent check on regulatory overreach, some argue that the new hurdles to establishing a guarantee program may cause toxic political consequences with damaging economic implications during crises (Gordon and Muller, 2011). First, specifically requiring presidents to ask Congress for a debt guarantee program would force the administration to publicly take complete political ownership over a major bank assistance program. Second, it is unclear whether Congress would be willing to authorize trillions of dollars in guarantees, even if such a magnitude might be necessary in a crisis. Both those dynamics mean that Congress may only approve a very limited guarantee scheme inadequate in scope to make a meaningful difference during a major liquidity crunch. Third, both Congress and the president might be tempted to push the FDIC to provide guarantees by placing institutions in receivership, an option with less political fallout but negative economic consequences. By effectively nationalizing major banks in a crisis, regulators could accelerate financial collapse by encouraging lenders to hoard capital in anticipation of major haircuts following receivership. Critics of Dodd-Frank argue that the “triple-key” approach previously in force under FDICIA, which required approval from supermajorities of both the FDIC and Fed Boards in addition to the executive branch, checks against imprudent guarantees without unduly constraining regulators during crises.

- Acharya, Viral and Raghu Sundaram. The other part of the bailout: Pricing and e…

- Ambrose, Brent W, Yiying Cheng, and Tao-Hsien Dolly King. The Financial Crisis …

- Bair, Sheila. Press Release: Statement by Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation…

- Bair, Sheila. Interviewed by Martin Smith. Frontline Oral Histories: the Financ…

- Berrospide, Jose. Bank Liquidity Hoarding and the Financial Crisis: An Empirica…

- Black, Jeffrey R, Seth A. Hoelscher, Duane Stock. Benefits of Government Bank D…

- Brunnermeier, Markus K. Deciphering the Liquidity and Credit Crunch 2007–2008. …

- Cave, Jason C. Statement of Jason C. Cave, Deputy Director for Complex Financia…

- FDIC. Transcript: Technical Briefing on the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Progr…

- FDIC. Transcript: Technical Briefing on the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Progr…

- FDIC. Transcript: Technical Briefing on the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Progr…

- FDIC. Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program. 2013.

- FDIC. Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program Frequently Asked Questions. 2009.

- Federal Register. 12 CFR Part 370 Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program; Final …

- Glader, Paul and Serena Ng. GE to End Government Loan Backing. The Wall Street …

- Gordon, Jeffrey N. and Christopher Muller. Confronting Financial Crisis: Dodd-F…

- Government Accountability Office. Federal Deposit Insurance Act: Regulators’ Us…

- Grande, Giuseppe, Aviram Levy, Fabio Panetta, and Andrea Zaghini. Public Guaran…

- Hoelscher, Seth A. and Duane Scott. Was Bond Insurance a Gift from the FDIC? 20…

- Layne, Rachel and Rebecca Christie. GE Wins FDIC Insurance for Up to $139 Billi…

- Shapiro, Robert J. and Doug Dowson. The Financial Hazards and Risks Entailed in…

- Turner, Adair. Speech: Shadow Banking and Financial Instability. Cass Business …

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. The Next Phase of Government Financial Stabili…

- U.S. Senate Report 111-176. The Restoring American Financial Stability Act of 2…

- Veronesi, Pietro and Luigi Zingales. Paulson’s Gift. Journal of Financial Econo…

Key Program Documents

-

Summary of the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program

FDIC overview of the program, with links to the program’s document archive.

-

Debt Guarantee Program Frequently Asked Questions

FDIC FAQs for the DGP.

-

Technical Briefing Related to the TLGP - Morning of October 14, 2008

FDIC answering technical questions from the banking community about TLGP, primarily the DGP.

-

Technical Briefing Related to the TLGP - Afternoon of October 14, 2008

FDIC answering technical questions from the banking community about TLGP, primarily the DGP

-

Technical Briefing Related to the TLGP - October 16, 2008

FDIC answering technical questions from the banking community about TLGP, primarily the DGP.

-

U.S. Guarantees During the Global Financial Crisis

YPFS case study examining the various guarantees adopted by the U.S. federal government during the global financial crisis of 2007-2009, including the DGP.

-

Guidance for Election Options and Reporting Instructions

notification for eligible institutions of the proper procedure/deadlines for opting in/out of the DGP as well as outlining debt reporting requirements.

-

Election Form Instructions

line-item instructions for filling out the election form.

-

TLGP Election Form

form submitted by all eligible institutions indicating whether the institution would participate in the program and whether it would issue debt under the 125% cap.

-

Guaranteed Debt Reporting Instructions

updated instructions for financial institutions on how to report issuances of guaranteed debt through FDICconnect.

-

Debt Guarantee Program Master Agreement

contract signed by all participating institutions that outlines the obligations of both FDIC and the debt issuer.

-

TLGP Final Rule

final rule for TLGP, including DGP, published in the Federal Register.

-

FINRA Regulatory Notice 08-75

notice on treating FDIC-guaranteed debt as Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE) eligible securities.

-

Exchange between SEC and FDIC regarding SEC Coverage of Guaranteed Debt - Original letter from FDIC to SEC.

request from FDIC for SEC to confirm FDIC’s interpretation of the Securities Act of 1933 to exempt guaranteed debt on the grounds that it is guaranteed by an instrument of the US.

-

Exchange between SEC and FDIC regarding SEC Coverage of Guaranteed Debt - Response from SEC to FDIC

response from SEC to confirm FDIC’s interpretation of the Securities Act of 1933 to exempt guaranteed debt on the grounds that it is guaranteed by an instrument of the US.

-

FIRNA Regulatory Notice 09-38 ¬

guidance on the treatment of guaranteed unsecured debt for regulatory purposes (under SEC’s Net Capital and Reserve Formula rules).

-

OCC Interpretive Letter No. 1108

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency regulatory guidance letter discussing registration of FDIC-guaranteed bonds with OCC.

-

FDIC Announces Plan to Free Up Bank Liquidity (10/14/2008)

official FDIC press release outlining the basics of TLGP, including DGP.

-

FDIC Chair’s Statement Announcing the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program – Joint Press Conference with Treasury and Federal Reserve (10/14/2008)

FDIC chair’s statement announcing the launch of the TLGP, including DGP.

-

FDIC Announces Series of Banker Calls on Its Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (10/16/2008)

FDIC press release announcing conference calls to field technical questions regarding TLGP provisions, including DGP.

-

Agencies Encourage Participation in Treasury's Capital Purchase Program, FDIC's Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (10/20/2008)

joint statement by FDIC, Treasury Department, and Federal Reserve urging institutions to participate in the DGP.

-

FDIC Issues Interim Rule to Implement the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (10/23/2008)

FDIC press release announcing publication of interim rule to implement TLGP (including DGP) with a 15-day comment period.

-

FDIC Chair’s Statement on the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program Interim Rule (10/23/2008)

FDIC Chair’s statement announcing the TLGP interim rule, including DGP.

-

FDIC Extends Opt-Out Deadline for Participation in the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (11/03/2008)

– FDIC press release announcing an extension of the opt-out deadline for TLGP (and DGP) from November 12 to December 5.

-

FDIC Board of Directors Approves TLGP Final Rule (11/21/2008)

FDIC press release announcing the approval of the TLGP (and DGP) final rule, detailing the major changes from the interim rule.

-

FDIC Extends the Debt Guarantee Component of Its Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (03/17/2009)

FDIC press release announcing the extension of the DGP to October 31, 2009.

-

FDIC Board Approves Phase Out of Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program Debt Guarantee Program to End October 31st (09/09/2009)

FDIC press release confirming end of DGP and announcing plans for creating a six-month Emergency Guarantee Facility.

-

GE Capital Announces Participation in FDIC’s Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program (11/12/08)

GE Capital letter to investors announcing their participation in the Debt Guarantee Program.

-

Banks Drop FDIC Crutch (Fortune, 05/12/09)

article discussing banks’ decisions to wean themselves off issuing FDIC-backed debt.

-

Banks Profit from US Guarantee (Wall Street Journal, 07/28/09)

article estimating the cost savings to banks, noting the success of the program in limiting borrowing costs and highlighting the impact of savings to banks.

-

Banks Face Loss of Debt Guarantee (Wall Street Journal, 09/10/09)

article discussing the DGP’s phase-out and legacy.

-

The Financial Crisis and Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program: Their Impact on Fixed-Income Markets (Ambrose et al, 2013)

examination of the impact of the DGP on guaranteed bond prices, overall borrowing costs, market liquidity, and bank solvency.

-

Paulson’s Gift (Veronesi and Zingales 2010)

examination of the net welfare impact of the Columbus Day interventions on the nine banks that received capital infusions from Treasury.

-

Benefits of Government Bank Debt Guarantees: Evidence from the Debt Guarantee Program (Black et al, 2015)

examination of the effect of the DGP on bond liquidity, borrowing costs, default risk, and equity value during the financial crisis.

-

Was Bond Insurance a Gift from the FDIC? (Hoelscher et al, 2013)

study of the effect of the DGP’s term structure on strong and weak banks to determine the relative subsidies that different classes of firms received during the crisis.

-

Public Guarantees on Bank Bonds: Effects and Distortions (OECD, 2011)

comparison of international bond guarantee programs and evaluation of the potential for such programs to introduce distortions in the financial sector.

-

Guarantees and Contingent Payments in TARP and Related Programs (Congressional Oversight Panel, 2009)

Congressional Oversight Panel evaluation of the creation, structure, cost/benefit, market impact, and broader effect of federal guarantees, including the DGP.

-

The Other Part of the Bailout: Pricing and Evaluating the US and UK Loan Guarantees (Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2008)

CEPR discussion of the differences between the U.S. and UK programs and the effect of those design differences on the financial system.

|

Debt Guarantee Program of the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program: United States Context |

|

|

GDP (SAAR, Nominal GDP in LCU converted to USD) |

$14,681.5 billion in 2007 $14,559.5 billion in 2008

Source: Bloomberg |

|

GDP per capita (SAAR, Nominal GDP in LCU converted to USD) |

$47,976 in 2007 $48,383 in 2008

Source: Bloomberg |

|

Sovereign credit rating (5-year senior debt)

|

As of Q4, 2007:

Fitch: AAA Moody’s: Aaa S&P: AAA

As of Q4, 2008:

Fitch: AAA Moody’s: Aaa S&P: AAA

Source: Bloomberg |

|

Size of banking system

|

$9,231.7 billion in total assets in 2007 $9,938.3 billion in total assets in 2008

Source: Bloomberg |

|

Size of banking system as a percentage of GDP

|

62.9% in 2007 68.3% in 2008

Source: Bloomberg |

|

Size of banking system as a percentage of financial system

|

Banking system assets equal to 29.0% of financial system in 2007 Banking system assets equal to 30.5% of financial system in 2008

Source: World Bank Global Financial Development Database |

|

5-bank concentration of banking system

|

43.9% of total banking assets in 2007 44.9% of total banking assets in 2008

Source: World Bank Global Financial Development Database |

|

Foreign involvement in banking system |

22% of total banking assets in 2007 18% of total banking assets in 2008

Source: World Bank Global Financial Development Database |

|

Government ownership of banking system

|

0% of banks owned by the state in 2008

Source: World Bank, Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey |

|

Existence of deposit insurance |

100% insurance on deposits up to $100,000 for 2007 100% insurance on deposits up to $250,000 for 2008

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Bank Debt Guarantee Programs

Countries and Regions:

- United States

Crises:

- Global Financial Crisis