Market Support Programs

United Kingdom: Asset Purchase Facility

Purpose

Gilt purchases: to “improve the functioning of the gilt market and help to counteract a tightening of monetary and financial conditions that would put at risk the MPC’s statutory objectives” (BoE MPC 2020b) Corporate bond purchases: “to improve market functioning and to reduce liquidity premia” (BoE MPC 2020b, 10)

Key Terms

-

Launch DatesFirst round: March 19, 2020 Second round: June 17, 2020 Third round: November 4, 2020

-

Operational DateGilts: March 25, 2020 Corporate bonds: April 7, 2020

-

End DateBEAPFFL holdings reached GBP 645 billion of gilts and corporate bonds by July 15, 2020

-

Legal AuthorityBank of England Act; exchange of letters with the chancellor of the Exchequer

-

Source(s) of FundingCreation of central bank reserves

-

AdministratorBank of England, Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited, Her Majesty’s Treasury

-

Eligible Collateral (or Purchased Assets)Gilts and corporate bonds

-

Peak UtilizationGilts: GBP 874.9 billion Corporate bonds: GBP 19.9 billion

The global outbreak of COVID-19 spurred investors to sell the British gilt in a synchronized fashion, which caused dysfunction in primary and secondary gilt markets. Yield spreads spiked, and primary dealers temporarily stepped back from dealing in gilts during a trading session on March 19, 2020. Liquidity premia were also high in non-gilt, fixed-income markets. That same day, the Bank of England (BoE) announced GBP 200 billion (USD 234 billion) of asset purchases through the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) to preserve liquidity in both gilt and corporate bond markets as part of larger efforts to prevent an undesirable tightening of financial and monetary conditions. Through the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited, BoE officials conducted reverse auctions to purchase gilts and investment-grade corporate bonds from primary dealers in these markets. The BoE established the APF in January 2009, as part of emergency actions meant to maintain the functioning of corporate credit markets during the Global Financial Crisis and achieve monetary policy goals; the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) expanded the size of the APF several times over the ensuing decade. The MPC voted to expand the APF twice after March 2020, by GBP 100 billion in June 2020 and GBP 150 billion in November 2020. Early assessments by individual BoE officials suggest that the initial intervention worked, but explanatory research is still in the early phases. During the COVID-19 crisis expansions to the APF, the BoE was criticized for its appearance of monetary financing and substandard communications of the justification and intent of the asset purchases.

In January and February 2020, news about the emergent COVID-19 crisis and significant public-health response gradually led to an abrupt repricing of assets, disruption of market liquidity, and high volatility in United Kingdom (UK) financial markets in March (BoE FPC 2020). By March 6, investors had already flown to safety by shifting their portfolios from risky to relatively safe and liquid assets (BoE FPC 2020; Hauser 2020). Primary and secondary corporate bond markets showed signs of distress (high bid-offer spreads, inability to issue) across term and risk rating (BoE FPC 2020). Corporate bond issuance had generally slowed throughout March, and investment-grade issuance did not pick up until later in the month.

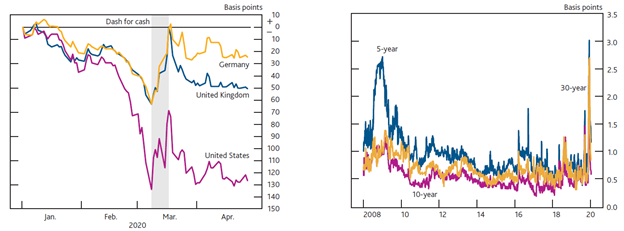

Initially, yields on sovereign debt fell, as demand rose for government bonds issued by advanced economies, and market participants expected cuts in short-term interest rates (BoE FPC 2020). However, the downward trend in yields on government securities reversed in mid-March: demand for government bonds plummeted because financial market participants sold them in a widespread effort to obtain cash and cash-like assets. Such “dash for cash” dynamics are further explained in Appendix A.

Gilts are one of the safest sterling assets, facilitate much of the UK’s economic activity, serve as a benchmark for other borrowing rates, and are important for the transmission of monetary policy (Hauser 2020). The Bank of England (BoE) recognized that the sudden COVID-19 outbreak and its associated turbulence could harm UK businesses and households, so it took action to prevent long-lasting economic damage (BoE MPC 2020e). In two special meetings (March 10 and March 19, 2020), the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted on emergency measures meant to alleviate temporary disruptions to business activity, liquidity in financial markets, and credit provision to the real economy, which are summarized in Appendix A, Figure 8.

On March 19, 2020, the MPC voted to purchase GBP 200 billionFOn March 20, 2020, this sum equated to about $234 billion; the USD-to-GBP exchange rate was about 1.16 (Bloomberg). of gilts and corporate bonds to maintain liquidity in both gilt and corporate bond markets and to prevent a potential tightening of monetary conditions (BoE MPC 2020b). The move accompanied other liquidity measuresFAt the same meeting, the MPC voted to reduce the Bank Rate by 15 basis points (bps) to 0.1% and increase borrowing allowance under the Term Funding Scheme with additional incentives for small and medium-sized enterprises (TFSME), a program that provided lenders with funding (meant for on-lending to SMEs) near the Bank Rate (BoE MPC 2020e). and expansive fiscal policy measures at both the global and local levels (BoE MPC 2020b; Douglas 2020).

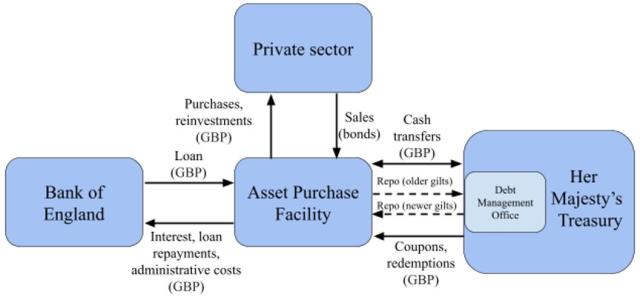

The BoE conducted the asset purchases through a subsidiary—the Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited (BEAPFFL)—and Her Majesty’s Treasury (HMT) indemnified its losses while coordinating risk standards with the BoE (BoE 2021c). The BEAPFFL was funded by loans from the BoE and financed by the creation of central bank reserves (Bailey 2020b; McLaren and Smith 2013). This general arrangement is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Diagram of Cash Flows to and from the Asset Purchase Facility

Source: McLaren and Smith 2013

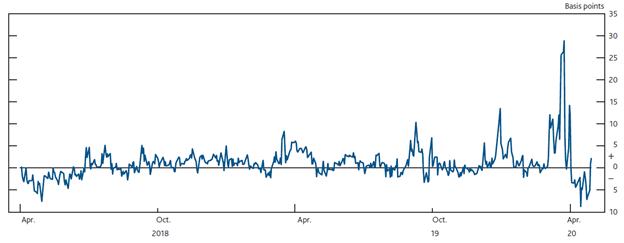

The BEAPFFL transacted in gilts and corporate bonds via reverse auctions; the operational procedures were mostly the same as in past asset purchase programs—all of which were conducted through the BEAPFFL—though the 2020 program exhibited a faster purchase pace than previous rounds of asset purchases (Bailey et al. 2020; BoE 2016b; BoE 2020h). The BEAPFFL purchases conventional gilts and specific corporate bonds issued by companies that conduct significant business activity within the UK economy (BoE 2020h). The BEAPFFL lends a portion of its gilt portfolio to the Debt Management Office (DMO) to prevent gilt market frictions (BoE/DMO 2009). As of February 2, 2022, BEAPFFL holdings were more than GBP 895 billion, with the purchase pace of later rounds slower after gilt market liquidity conditions had stabilized (BoE MPC 2020c; BoE MPC 2022). On February 2, 2022, the BoE MPC voted unanimously to reduce the stock of assets held in the BEAPFFL; the BoE stopped reinvesting maturing proceeds from maturing assets and pledged to completely unwind its corporate bond holdings by the end of 2023 (BoE MPC 2022).

Given the newness of the BoE’s interventions during the COVID-19 crisis, there are not yet any studies that analyze the effects of the BoE’s gilt and corporate bond purchases. BoE officials have said the first asset purchases fixed market dysfunction. Criticisms about the BoE’s asset purchases include concerns about the BoE’s communication regarding the justification and objectives for its asset purchase program, the appearance of monetary financing, and threats to central bank independence.

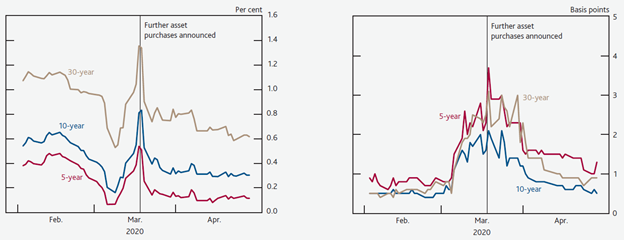

In the first half of 2020, BoE spokespeople usually cited two types of evidence that the APF worked: (1) declining spreads between headline financial rates, and (2) the fact that gilts and corporate bonds continued to trade after market dysfunction. Appraising the expansions in March 2020, the BoE emphasized that the combination of asset purchases and HMT’s programs on workers’ support, business assistance, tax deferrals, and other fiscal relief together improved confidence in sterling markets: the sterling appreciated slightly, gilt yields fell, and the yield curve flattened (BoE MPC 2020b; UK Gov 2020). At the same MPC meeting, the BoE also acknowledged that while the gilt market calmed, repo and money markets remained unstable and London Interbank Offered Rate–overnight index swap (LIBOR-OIS) spreads were still high (BoE MPC 2020b). In a June 2020 interview with Sky News, Governor Andrew Bailey said that the central bank’s recent APF interventions worked because they restored order to markets (Bailey 2020a).

Later in 2020, BoE officials offered more specific explanations about how and why the program worked. Bailey et al. (2020), issued in August, say that the BEAPFFL’s asset purchases were particularly effective because they happened during a time of market dysfunction; the authors speculate that the purchases restored order to gilt markets through a liquidity channel.FBoE’s Independent Evaluation Office (2021) defines the liquidity channel as: “By committing to buying certain bonds, central banks can reassure other investors that [the investors] can sell these bonds if they need to. Given that holding these bonds is now less risky, their price rises. This channel is most effective when markets are stressed and demand for liquidity is high” (12). Bailey et al. (2020, 21–23) further explains that the front-loaded pace of March purchases may have played an additional role in preventing the tightening of monetary conditions; the authors express confidence that BEAPFFL’s rapid rate of gilt purchases carried “a positive spillover effect on financial stability.” In an October 2020 speech, Dave Ramsden, deputy governor for markets and banking at the BoE, argues that the asset purchase program improved market functioning through three types of metrics: price and volatility, liquidity and depth of market, and gilt financing (repo) rates (Ramsden 2020).

CriticsFBoE’s former deputy governor Paul Tucker called BoE independence into question at a Royal Economic Society event (Giles and Tucker 2020). Tucker asserts that the BEAPFFL purchased more than what was necessary for market liquidity, and that this was not a “classic market maker of last resort operation” (Giles and Tucker 2020, 3:00). The extensive scale of the COVID-19-related asset purchases is the root of Tucker’s criticism. In the past, other former BoE officials have pointed to alternative threats to central bank independence. Allen (2017) suggests that past rounds of quantitative easing, too, compromised BoE’s independence because the BoE’s small capital base limits the central bank’s ability to perform unconventional monetary policy without the explicit financial backing and permission of HMT. have expressed concern about pandemic-driven threats to central bank independenceFFor more information about monetization of fiscal deficits during the COVID-19 crisis, refer to Lawson and Feldberg (2020). (Bosley 2020; HoL EAC 2021). In 2021, the BoE’s asset purchase program became the central subject of a formal inquiry by the House of Lords’ Economic Affairs Committee (HoL EAC 2021). One of the inquiry’s aims was to investigate whether BEAPFFL purchased assets to decrease HMT’s long-term borrowing costs—rather than to meet the BoE’s statutory mandate—in its response to the COVID-19 crisis (HoL EAC 2021). The inquiry was motivated by the concern that the BoE’s ongoing emergency measures threatened its ability to conduct monetary policy separately from the government’s agenda (HoL EAC 2021). To explain external allegations of deficit financing, the inquiry cites the following as evidence: (1) the fact that the BoE and fiscal authorities simultaneously enacted expansive policy measures involving large quantities of government debt; and (2) inconsistent communicationFThe communicative issues were twofold. On separate occasions in May and June 2020, Governor Bailey noted the close relationship between government funding and BoE’s asset purchase program (HoL EAC 2021). Additionally, BoE officials expressed public disagreement with one another over the primary purpose of the asset purchase program—monetary policy objectives or market functioning. from acting BoE officials about the purposes of the asset purchase program (HoL EAC 2021). A central bank’s ability to conduct independent monetary policy is widely considered essential for inflation control, so any lasting damage to the BoE’s independence could translate to the BoE’s inability to influence inflation and maintain financial stability (HoL EAC 2021; Rosengren 2019).

The BoE has publicly rejected claims of monetary financing. In an opinion submitted to the House of Lords’ inquiry, the BoE argues that underlying economic conditions observed in Q1 2020 warranted similarly expansive fiscal and monetary policy; given the state of the UK, the BoE argues, the fiscal authorities and central bank had overlapping goals (HoL EAC 2021). The BoE says that it was justified in BEAPFFL’s purchasing large amounts of government debt from the secondary market while the government issued debt to the primary market (BoE 2021a). The BoE also cites “well-anchored” inflation expectations to argue that it maintains perceptions of independence and credibility in the eyes of investors (BoE 2021a, 6). Though the BoE acknowledges the potential costs (“large public sector balance sheets and mispriced private sector risks”) of the asset purchase program, it also pledges to develop its communication strategies so that the public can better understand the BoE’s decision-making process and goals for the program (BoE 2021a, 7, 15).

The general academic consensus on the UK’s use of asset purchases is positive for both financial and macroeconomic conditions. Researchers estimate that the BoE’s first two asset purchase programs (collectively worth GBP 325 billion, or about 20% of annual GDP at the time) lowered 10-year gilt yields between 50 basis points (bps) and 100 bps (Bailey et al. 2020). Scholars also find that the Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme (CBPS), which refers to BEAPFFL’s purchases of corporate bonds, alleviated monetary conditions via lower corporate credit spreads in 2016. It is difficult to estimate the effects of asset purchase programs on macroeconomic variables due to the time lag of inflation and output; still, scholars hold that the BoE’s past expansion(s) of the APF have most likely increased the UK’s GDP levels and aided the BoE in approaching its statutory objective of a 2% inflation target (Bailey et al. 2020; Smith 2020). For in-depth literature reviews on the financial and macroeconomic effects of the BoE’s asset purchase programs, please refer to the BoE’s Independent Evaluation Office (IEO) (BoE IEO 2021), Bailey et al. (2020), and Borio and Zabai (2018).

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

1

The BoE announced a GBP 200 billion increase to the BEAPFFL’s holdings of gilts and corporate bonds on March 19, 2020, to support the functioning of these and other financial markets early in the COVID-19 crisis (BoE 2020a). Prior to the crisis, the BEAPFFL held GBP 435 billion in gilts and GBP 10 billion in corporate bonds (BoE MPC 2020a).

The BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee, in the minutes of its special meeting on March 19, frames the asset purchases as an emergency measure that also satisfied monetary policy objectives. For gilt purchases, the MPC says the goal was to “improve the functioning of the gilt market and help to counteract a tightening of monetary and financial conditions that would put at risk the MPC’s statutory [inflation] objectives” (BoE MPC 2020b, 9). For corporate bond purchases, it says, “Given recent market developments, such purchases would help to improve market functioning and to reduce liquidity premia” (BoE MPC 2020b, 10). The MPC describes market stability and longer-horizon monetary policy objectives as mutually reinforcing. March minutes state that the MPC was also prepared to further expand the program, if necessary.

The BoE announced similar increases to the BEAPFFL of GBP 100 billion in June 2020 and GBP 150 billion in November 2020. Later rounds were primarily meant to provide monetary stimulus rather than to support securities market liquidity (BoE 2020b; BoE MPC 2020d). The June and November minutes acknowledge that gilt markets had stabilized and cite the MPC’s statutory monetary policy objectives (BoE MPC 2020b; BoE MPC 2020c; BoE MPC 2020d). As the year progressed, the MPC also softened its language about the scope of further action. The June and November minutes note that the MPC was ready to “increase the pace” of government bond purchases if market functioning deteriorated (BoE MPC 2020b, 12; BoE MPC 2020c, 13; BoE MPC 2020d, 12).

This case study focuses on the first round of asset purchases during the COVID-19 crisis due to its focus on promoting liquidity in gilt and corporate bond markets.

Part of a Package

1

The BoE did not include asset purchases in its initial COVID-19 measures decided upon at its first special meeting on March 10, 2020, as shown in Figure 8 in the Appendix (BoE MPC 2020e). The events of the following week led the BoE to vote on asset purchases at the second special meeting on March 19 (BoE 2020a; BoE MPC 2020b).

By early March 2020, public financial institutions and central banks had cut interest rates, launched liquidity facilities, and purchased assets of public and private origin (Douglas 2020). These were efforts to shield economies from financial disruption stemming from the COVID-19 crisis. In the UK, the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee voted to cut the Bank Rate by 50 bps, bringing the headline interest rate to 0.25% on March 11, 2020 (BoE FPC 2020). Meeting minutes note the “role for monetary policy to help UK businesses and households bridge a sharp but temporary reduction in activity” (BoE MPC 2020a, 6). To further preserve small businesses’ access to credit, the MPC decided to offer banks a Term Funding Scheme with additional incentives for small and medium-sized enterprises (TFSME) at, or near, the Bank Rate (BoE MPC 2020a).

Within the UK, fixed-income strategists expected the government to launch ambitious fiscal stimulus measures to counter the effects of COVID-19 on businesses and consumers (Ainger and Ritchie 2020). Her Majesty’s Treasury’s Budget 2020, announced on March 11, described just GBP 30 billion of coronavirus relief, and the government’s five-year macroeconomic forecasts limited the incorporation of additional COVID-19 spending into its projections of fiscal expenditure (HMT 2020).

On March 17, Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced additional emergency support for both new and existing programs, and the additions were not captured by the Budget 2020’s GBP 30 billion figure (Sunak 2020a).

Worldwide, financial market participants moved money away from risky assets and government bonds, and shifted to cash,FCzech et al. (2021) describes the “dash for cash” dynamic that led to the sterling market dysfunction. especially US dollars (BoE MPC 2020b). Given the massive public costs of emergency programs in the UK, some investors were reportedly concerned about the source of demand for the soon-to-be-issued gilts that would pay for the stimulus (Aldrick 2020b). Their worries showed in the data, and by mid-March, UK financial markets exhibited heightened volatility: the USD-to-GBP exchange rate hit a 35-year low, risky asset prices fell, investment-grade and high-yield bond spreads soared, and gilt yields rose (Giles, Parker, and Payne 2020). On March 19, the Debt Management Office, which is HMT’s office responsible for issuing the government’s wholesale sterling debt, successfully completed the morning’s auction; thereafter, gilt markets entered a standstill and could not function until the BoE intervened (Aldrick 2020a). Yields on government debt peaked and gilt markets froze, leaving the DMO temporarily unable to sell government debt to gilt-edged market makers (GEMMS) because traders were hesitant to determine the price of government debt (Aldrick 2020b).

On the same day, the MPC convened in a special meetingFThrough the first quarter of 2020, the MPC had met off-cycle only four times in its 23 years of existence: after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001; during the Global Financial Crisis on October, 8 2008; and during the COVID-19 crisis on March 10 and 19, 2020 (Bailey 2020a; BoE MPC 2008). and obtained permission from HMT for the BEAPFFL to purchase GBP 200 billion of gilts and nonfinancial, investment-grade corporate debt from the secondary market to address the worsening financial conditions of gilt and corporate bond markets (BoE 2020a; BoE MPC 2020b). “Had the Bank not stepped in, things would have gotten very difficult,” said Sir Robert Stheeman, chief executive of the DMO (Aldrick 2020a). BEAPFFL began purchasing gilts on March 25 and corporate bonds on April 7, 2020 (BoE 2020e; BoE 2020g).

Legal Authority

1

The APF was the product of coordination between HMT and the BoE during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), although it is unclear which agency first raised the idea.FChancellor Darling has claimed that the APF started as BoE’s idea while Governor King has asserted the opposite (Darling 2021; King 2012). HMT formally requested and authorized the BoE to set up and operate the APF on January 19, 2009 (Darling 2009b; Darling 2011; HMT 2009). With an initial size of GBP 50 billion, the APF’s original objective was “to increase the availability of corporate credit, in order to support the Bank of England’s responsibilities for financial stability and monetary stability in the United Kingdom” (Darling 2009b, 1). Introduced alongside several measures meant to reassure markets and stabilize the economy, the APF aimed to improve corporate credit conditions, especially for larger companies, by “reducing the illiquidity of the underlying instruments” (Darling 2011, 203; HMT 2009). For more information on the APF’s legal origins, please refer to the Appendix B.

The BoE decides the value and composition of asset purchases through the BEAPFFL via majority MPC vote, similarly to how it set the Bank Rate (BoE 2021d; BoE 2021e). Unlike with traditional monetary policy, however, the BoE must obtain HMT’s explicit permission before changing the size of the BEAPFFL’s assets because of the HMT indemnification (BoE IEO 2021; HoL EAC 2021).

The BoE had to seek HMT’s approval three times in March, June, and November 2020 to expand HMT’s indemnity of the BEAPFFL, which allowed the BoE to pursue monetary policy objectives through additional asset purchases (“quantitative easing”) (Bailey 2020b; Bailey 2020c; Bailey 2020d; Sunak 2020b; Sunak 2020c; Sunak 2020d).

Governance

1

The BoE has implemented additional internal governance and risk oversight measures for the APF that it does not have for its traditional, independent monetary policy decisions. Those measures are necessary because of the risk associated with asset purchases through quantity, maturity, and type of asset (BoE IEO 2021).

The BoE’s asset purchase decisions span its policy, operations, and risk functions (BoE IEO 2021). For that reason, in 2018, the BoE established an internal memorandum of understanding to manage terms of engagement and scope of decision-making between BoE’s Court of Directors,FThe BoE Court of Directors is the governing body responsible for setting BoE’s objectives and strategies (BoE 2019b). The Court monitors BoE’s “performance in relation to its objectives, the exercise of [BoE’s] statutory functions and the processes of the policy committees,” and its five executive members are appointed by the Crown (BoE 2019b, 3). Executive, and MPC (BoE 2018; BoE IEO 2021). While the MPC selects the BoE’s tools and purchase amounts, BoE’s Executive determines the operational framework to create and execute the MPC’s decisions; BoE’s Court also delegates to the Executive the responsibility of assessing risks to BoE’s balance sheet (BoE IEO 2021). The BoE’s Independent Evaluation Office argues that this high-level arrangement among the MPC, Executive, and Court allows the BoE to remain flexibleFThe BoE IEO (2021, 27) reports that the BoE saw occasional “grey areas” where existing internal governance guidelines did not distinguish the BoE branch responsible for setting a feature of asset purchases (for example, the maturity buckets of gilts). The IEO also asserts that the BoE navigated these gray areas successfully and that it may be operationally advantageous to not preassign responsibilities for every possible dimension of asset purchases. during times of crisis. The Executive assesses risk by engaging the BoE’s relevant committees:

- The Audit and Risk Committee of the Court “assists the court in meeting its responsibilities for maintaining efficient systems of financial reporting, internal control and risk management”;

- The Executive Risk Committee “oversees the operation of [the BoE’s] Risk Management Framework”;

- The Financial Operations and Risk Committee “provides advice and challenge on all material risk issues relevant to the Bank’s balance sheet”; and

- The Executive Committee “deals with issues of policy, strategy, and management that are not reserved for the Court or the Bank’s three statutory policy committees.” (BoE IEO 2021, 29–30)

General information about the BoE’s risk management practices, which also apply to asset purchases, can be found in the IEO’s 2021 report.

The external arrangement between the BoE and HMT makes this asset purchase program unique because the BoE conducts its asset purchases with a separately indemnified fund (BEAPFFL), unlike many other central banks, which use their own balance sheets to conduct similar purchases; the purpose is to keep the MPC “operationally independent [yet] fully accountable” (BoE IEO 2021, 10). IEO argues that this BoE/HMT arrangement is “well designed and [has] functioned effectively” (BoE IEO 2021, 24). However, IEO also suggests that a large and unexpected reversal of cash flows between HMT and the BoE could carry reputational risk for the BoE.

Administration

1

The APF is jointly administered by HMT and the BoE; this arrangement follows a memorandum of understanding (MoU) mandated by the Financial Services Act 2012 (FSA 2012). In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, the UK Parliament passed the FSA 2012, which reformed the UK’s frameworks for financial regulation and supervision (FSA 2012; Metrick and Rhee 2018). Section 64 of the FSA 2012 requires HMT, the BoE, and the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) to formally coordinate any actions relating to financial stability, and Section 65 requires the institutions to plan their coordination through a publicly available MoU on resolution planning and crisis management (FSA 2012). Under the MoU, the BoE has “primary operational responsibility for financial crisis management” while HMT has “sole responsibility for any decision involving public funds” (HMT 2017, 1). This division of labor is reflected in the APF’s administration.

The BoE conducts asset purchases on behalf of the BEAPFFL, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of the BoE (BoE 2020h; BoE 2021f).

A variety of BoE staff are involved in the implementation of BEAPFFL’s purchases. Under the BoE’s Sterling Monetary Framework, the MPC determinesFTo establish the appropriate size of APF holdings, BoE’s MPC relies on research and analysis from the Monetary Analysis, Markets, and the Research Hub, with further input from Financial Stability Committee and Prudential Regulation Authority (BoE IEO 2021). the total stock of monetary stimulus, while the BoE’s Executive is responsible for deciding how to deliver the stimulus and manage risk (BoE IEO 2021). Four executive directors (EDs: finance, markets, banking, and monetary analysis) serve as the APF directors. The BoE’s Markets Directorate is responsible for setting BEAPFFL’s purchase parameters “to ensure smooth market functioning” (BoE IEO 2021, 11). The bank’s risk management officials further evaluate operational choices, advise the EDs for further financial and nonfinancial risks, and consult with legal experts on relevant issues. Upon implementation, the BoE’s dealers execute the auctions and cooperate with counterparties, and the Markets Directorate’s middle and back offices process the trades. Afterwards, the BoE’s Communications Directorate delivers asset purchase decisions through MPC minutes and the Monetary Policy Report, and the BoE’s agents further communicate BoE’s decisions in their regions.

HMT coordinates APF’s risk and control frameworks with the BoE (BoE 2020h; BoE 2021c). Together, they observe the BEAPFFL’s operations, consider potential risks to public funds, and discuss potential effects on specific sectors and markets (BoE 2021c). HMT fully indemnifies the BEAPFFL’s net financial losses, so the BEAPFFL pays/receives remittances at quarterly intervals (McLaren and Smith 2013). See Key Design Decision No. 10, Source(s) of Funding for more discussion of these cash flows.

Within the HMT, the DMO manages the UK’s sovereign debt issuances while attempting to minimize the government’s long-term financing costs (DMO n.d.). DMO issues gilts to primary dealers called gilt-edged market makers, who trade gilts on secondary markets (DMO 2021). After the BEAPFFL buys gilts on the secondary market, it may lend a proportion of its gilts to DMO through the Debt Management Account for the purpose of the DMO’s short-term repo activities with market participants (BoE 2021c; BoE/DMO 2009). See Key Design Decision No. 13, Loan or Purchase for more information about the BEAPFFL’s gilt repo activities with DMO.

Communication

1

The BoE announced the MPC’s decisions about the APF in market notices and statements of varying specificity (BoE 2020a; BoE 2020d). During the COVID-19 crisis, the BoE announced an increase of GBP 200 billion to the BEAPFFL on March 19, 2020. On April 2, the BoE clarified that at least GBP 10 billion of the new purchases would consist of corporate bonds (BoE 2020a; BoE 2020c). The BoE also released MPC meeting minutes and summaries several days after the meetings took place; these minutes describe the MPC’s justification and economic contexts (BoE MPC 2020b; BoE MPC 2020c; BoE MPC 2020d).

Despite the BoE’s formal channels and procedures for communicating actions to the public, the House of Lords’ Economic Affairs Committee criticized the BoE for mixed messaging (HoL EAC 2021). On separate occasions in May and June 2020, Governor Bailey noted the close relationship between government funding and the BoE’s asset purchase program. BoE officials later publicly disagreed whether the primary purpose of the program was to support monetary policy objectives or market functioning. Critics from the House of Lords argued that the BoE did not sufficiently explain how the asset purchases served BoE’s mandate, so some of Governor Bailey’s public statements, they contended, may have convinced some observers that the BoE engaged in monetary financing during the crisis.

Disclosure

1

The chancellor of the Exchequer and BoE governor exchange letters about the APF whenever the BoE seeks to increase the size of HMT’s indemnity; these letters reiterate the BoE’s policy goals, relevant economic trends, and HMT’s administrative expectations. The letters that the parties sent during the COVID-19 crisis also explicitly state that the BoE’s secondary-market asset purchases had no direct effect on the DMO’s primary-market gilt issuances (Bailey 2020b; Sunak 2020b).

According to the MoU on resolution planning and financial crisis management, the BoE has several communicative responsibilities with HMT, Parliament, and the public (HMT 2017). The BoE is required to update HMT and the public on the progress of any financial crisis, along with BoE’s actions to mitigate the crisis. The BoE and HMT also must inform the markets of relevant regulatory reporting requirements and the use of BoE’s balance sheet.

The BoE publishes annual APF accounts, which are audited by the National Audit Office (BoE IEO 2021). The accounts contain statements on BEAPFFL’s income, financial position, and cash flows (BoE 2021b). The notes on the financial statements describe the BEAPFFL’s assets according to securities class, fair valuation, credit risk, geographical concentration, sectoral concentration, and maturity, among other analyses. The BoE also posts quarterly APF reports summarizing the gilt and corporate bond purchases during the prior three months (BoE 2021h). The BoE separately publishes APF results and usage data. For gilt transactions, the BoE publishes detailed operations data, including: operation dates, settlement dates, ISIN, bond identifiers, total offers received, total allocation (in both proceeds and nominal terms), allocation of noncompetitive auctions, weighted-average accepted yield, weighted-average accepted price, highest accepted price, allocation at highest price, and lowest accepted price (BoE 2022). For corporate bonds, the BoE publishes only the level of holdings and sectoral allocation.

SPV Involvement

1

The Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited was incorporated as the BoE’s subsidiary on January 30, 2009 (UK Gov 2021). BEAPFFL is fully indemnified by HMT, so HMT absorbs any losses arising out of and receives all gains coming from the BEAPFFL (BoE 2021c). The BoE relies on BEAPFFL to purchase private sector securities not eligible for open market operations (OMOs); as of January 2008, only gilts were eligible for OMOs (BoE 2008; HMT 2009). The securities resulting from BEAPFFL’s asset purchases do not appear on the BoE’s balance sheet (BoE 2021b). The BoE records only its outstanding loans to the BEAPFFL as assets under the Banking Department.

Program Size

1

For the first round of asset purchases during the COVID-19 crisis, the BoE specified an additional GBP 200 billion of assets, establishing an upper limit of GBP 645 billion on BEAPFFL’s collective holdings of gilts and corporate bonds (BoE 2020a). To determine the level of gilts and corporate bond purchases necessary to fulfil its remit, the MPC considered the sizes of both the APF and the Covid Corporate Financing Facility, a market liquidity program in which the BoE purchased commercial paper financed by the creation of central bank reserves (BoE MPC 2020b). After two additional expansions to APF, BEAPFFL held about GBP 874.9 billion in gilts and GBP 19.9 billion in corporate bonds as of February 2, 2022 (BoE 2022).

From March 25 through June 17, 2020, BEAPFFL purchased about GBP 173.6 billion in gilts, at an average pace of about GBP 13.5 billion per week—more than twice the pace of the first asset purchases during the GFC (Bailey et al. 2020; BoE 2021i). The BoE front-loaded the program “as much as was operationally possible” to prevent monetary tightening (BoE MPC 2020b, 9). Bailey et al. (2020) speculates that the BoE’s front-loaded purchase pace may have been more effective than a slower, uniform purchase pace during COVID-19-induced market stress. Given the self-accelerating dynamics of market dysfunction, the argument goes, more firepower was needed at the beginning of the turbulence to prevent a counterfactual downward spiral from developing later. After the initial round of purchases during the COVID-19 crisis, the MPC voted to slow the rate of asset purchases to an average rate of about GBP 4.5 billion per week—one-third the weekly pace of the first round—because liquidity conditions had stabilized by mid-June 2020 (BoE 2021i; BoE MPC 2020c).

Source(s) of Funding

1

As shown in Figure 1, the BoE provides loans to the BEAPFFL so that it may purchase assets, financed by the creation of central bank reserves (Bailey 2020b; McLaren and Smith 2013). Depending on the MPC’s policy stance, the BEAPFFL may repay loan principal or reinvest proceeds from gilt redemptions (McLaren and Smith 2013). Similarly to how it treats gilt proceeds, BEAPFFL may occasionally reinvest the corporate bond cash flows back into eligible corporate bonds (BoE 2021f). If the BoE needs the BEAPFFL to sell these assets, the BoE may charge intermediary accounts, which requires market participants to pay cash to the intermediaries. The BEAPFFL repays loan interest (plus the BoE’s administrative costs) at the Bank Rate with incoming gilt coupon payments (McLaren and Smith 2013).

Since April 1, 2013, HMT has indemnified the BEAPFFL’s losses and transfers cash to/from the BEAPFFL every quarter (BoE 2021c). These transfers represent “actual cash movements,” such as interest payments or administrative costs; no cash is transferred due to “non-monetary gains or losses” such as variations in the market prices of gilts or corporate bonds (BoE 2019a, 1). Between March 1, 2020, and February 28, 2021, cumulative transfers stood at GBP 13.7 billion (BoE 2021c). Nearly all the cumulative transfers have gone from the BEAPFFL to HMT (BoE IEO 2021). The quarterly payment system allows the UK government to manage its cash with increased flexibility, similar to the processes of the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan (BoE 2021c).

When BEAPFFL conducts initial rounds of asset purchases, the direction of net cash transfers likely has been from the BEAPFFL to HMT because coupon payments exceed interest costs in a low-interest-rate environment (McLaren and Smith 2013). However, this will likely reverse over time because the BEAPFFL typically purchases gilts above par (at a price greater than redemption value) (McLaren and Smith 2013). Given that the price of gilts approaches redemption value as the gilt approaches maturity, the redemption value probably will not cover the principal of the loan originally used to purchase the gilt. The BoE acknowledges that the APF involves large and variable cash transfersFThe size, timing, and direction of cash transfers depends on several factors, including the future path of the Bank Rate, the path of gilt sales, and the effect of sales announcements on the “term premia” (difference between the Bank Rate and the gilt yield curve) (McLaren and Smith 2013). The path of the Bank Rate directly affects the BEAPFFL’s interest payments to BoE and influences the gilt yield curve, which affects the market value of the APF’s gilt holdings. The path of gilt sales sets the time that remains in the asset purchase schedule, affecting the gilt sales prices. Similar to the path of the Bank Rate, the announcement of gilt sales influences the gilt yield curve and the consequent market value of the BEAPFFL’s gilt holdings. between the BEAPFFL and HMT and stresses that the BEAPFFL’s net gains or losses should not be used as a stand-alone metric for gauging the success or failure of the APF. Rather, BoE officials have argued that the success of the APF should be determined by its influence on corporate credit conditions, nominal spending, and the medium-term inflation target.

Eligible Institutions

1

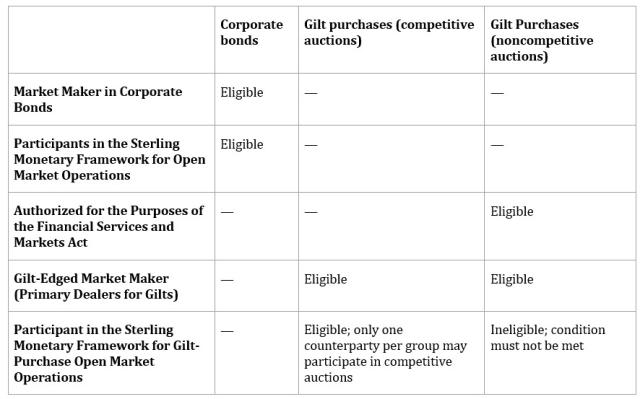

BEAPFFL purchases assets from banks and broker-dealers, who otherwise transact in the assets primarily with nonbank owners (BoE 2021f). Counterparty eligibility for the APF depends on the type of asset, the format of the auction, and the identity of the seller, as described by Figure 2.

Figure 2: Eligibility Criteria for APF Purchase Schemes

Auction or Standing Facility

1

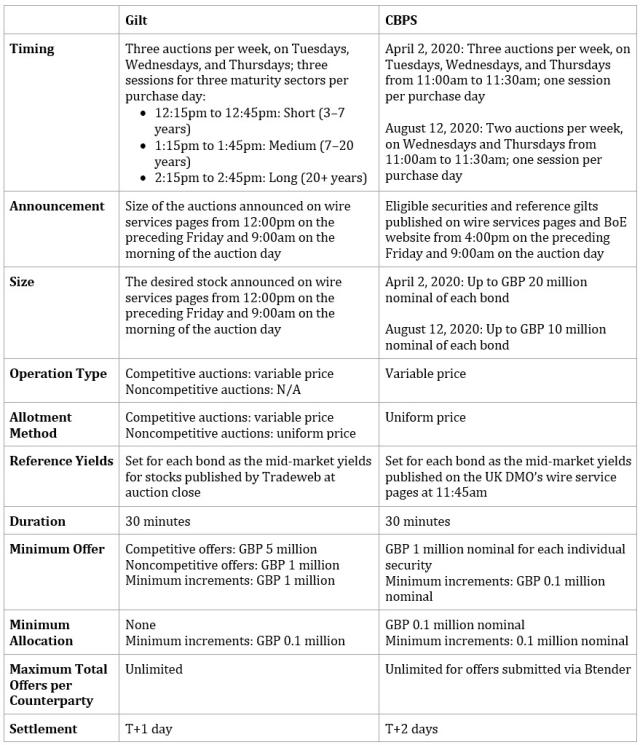

Gilt purchases. To purchase gilts, BEAPFFL conducts reverse auctions with discriminatory (i.e., variable) pricing (BoE 2020h). Each successful counterparty receives their offered sales price, in central bank reserves, in exchange for the security (BoE 2021f). To appraise offers in a competitive auction, BEAPFFL refers to the market yield of each gilt at the end of the auction, arranges the offers in descending yield order, accepts those that it deems attractive, and repeats this process until it has bought the desired amount of gilts (BoE 2020h; BoE 2021f). For noncompetitive auctions, BEAPFFL allocates the stock of securities at a weighted-average price, which comes from the relevant segment of the competitive auction (BoE 2020h). There are no restrictions on the number of offers and no limits on the proportion(s) of auctions to be allocated to particular gilts or counterparties (BoE 2021f). BEAPFFL may also reinvest the gilt cash flows into other gilts.

Corporate bond purchases. When BEAPFFL purchases corporate bonds with the APF, this is known as the Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme (BoE 2016a). To conduct the CBPS, BEAPFFL uses reverse auctions (BoE 2021f). BEAPFFL first collects offers and ranks them by attractiveness. In contrast to its gilt purchases, BEAPFFL uses a uniform pricing system to price corporate bonds because their markets are less liquid and more diverse than gilt markets. BEAPFFL pays a single clearing price—equal to the highest accepted price—for all successful offers of a given bond. Though BEAPFFL uses reverse auctions for the CBPS, it has the discretionary authority to purchase through other methods, such as bilateral purchases, on secondary markets (BoE 2020a). The MPC also reviews the possibility of purchasing corporate bonds on the primary market.

Loan Amounts (or Purchase Price)

2

BEAPFFL purchases. BEAPFFL purchases gilts and corporate bonds from the secondary market, though the BoE keeps open the possibility of BEAPFFL’s purchasing corporate debt through primary markets (BoE 2020a). A full list of operational purchase parameters can be seen in Figure 3. The BoE conducts all its APF operations through Btender, the BoE’s electronic trading system (BoE 2020h, 3). More information about APF settlement procedures and contingencies can be found in the APF Operating Procedures (BoE 2020h).

Figure 3: Operational Purchase Parameters for APF Schemes

BEAPFFL Loans. After the BEAPFFL buys gilts on the secondary market, it may lend a proportion of its gilts to DMO through the Debt Management Account for DMO’s short-term repo activities (BoE 2021c; BoE/DMO 2009). In exchange for BEAPFFL’s gilts, the DMO posts government securities of equal value as collateral, so there is no net change in the value of the BEAPFFL’s gilt portfolio (BoE/DMO 2009). The purpose of on-lending is to resolve market frictions stemming from the BEAPFFL’s asset purchases. The BEAPFFL allows the DMO to use at least 10% of each of the BEAPFFL’s gilts; the percentage is higher for gilts for which BEAPFFL owns most of that gilt’s free float, the amount of publicly tradable gilts. On April 22, 2020, the BoE doubled the gilt lending limits to minimize frictions between the BEAPFFL and DMO (BoE 2020d). That decision gave the DMO access to more than GBP 30 billion of the BEAPFFL’s gilt holdings. By doubling the limits, the BEAPFFL attempted to support DMO repo facilities, which use gilts as collateral, from BEAPFFL’s extensive gilt purchases.

To purchase gilts, BEAPFFL conducts reverse auctions with discriminatory pricing (BoE 2020h). To purchase corporate bonds, the BoE uses reverse auctions with uniform pricing (BoE 2021f). See Key Design Decision No. 12, Auction or Standing Facility for more information about the role of pricing in the BoE’s reverse auctions.

Eligible Collateral or Assets

1

Gilt purchases. BEAPFFL purchases conventional gilts with remaining maturities of at least three years (BoE 2020h). BEAPFFL does not purchase index-linked gilts, rump stocks, or stocks with an outstanding issue size below GBP 4 billion. BEAPFFL also avoids purchasing gilts for which BEAPFFL possesses at least 70% of the free float. BEAPFFL waits at least one week after the DMO issues debt before purchasing it to avoid the impression of monetary financing (Aldrick 2020b; BoE 2020h). BEAPFFL also avoids transacting in DMO’s reissuances one week before and one week after the reopening; the purposes are to maintain central bank independence and to prevent GEMMS from simultaneously buying gilts from DMO and selling them to BEAPFFL.

Since 2016, the BEAPFFL’s asset purchases have mostly maintained the same operating procedures (BoE 2016b; BoE 2020h). However, for the expanded APF in response to the COVID-19 crisis, the MPC changed the definition of residual maturities from seven to 15 years to seven to 20 years (medium) and from 15+ years to 20+ years (long) to “free up additional headroom to purchase gilts” equally across the maturity sectors (BoE MPC 2020b, 9). In this context, “headroom” refers to “the amount of gilts that [the BoE] can purchase without exceeding self-imposed limits” (HoL EAC 2021, 28). To summarize: the BoE intends for the BEAPFFL to purchase gilts equally across three residual maturity buckets: three to seven years (short), seven to 20 years (medium), and 20+ years (long) (BoE MPC 2020b).

Corporate bond purchases. BEAPFFL may purchase corporate bonds with the following features:

- Conventional senior unsecured or secured, unsubordinated debt;

- Bonds rated investment grade by at least one major rating agency and subject to the BoE’s assessment process;

- Cleared and settled through Euroclear and/or Clearstream;

- Minimum amount in issue of GBP 100 million;

- Minimum residual maturity of 12 months; no perpetual debt;

- At least one month since the security was issued; and

- Admitted to trading on the official listing of a European Union stock exchange, or, at the BoE’s discretion, listed on a multilateral trading facility operated by a stock exchange regulated in the European Economic Area. (BoE 2020c)

Complex, nonstandard, convertible, and exchangeable bonds are not eligible (BoE 2020h). BEAPFFL normally accepts bonds with “Spens clauses,” meaning that early redemption pays outstanding principal and forgone interest or principal payments discounted according to the redemption yield of a similar gilt. BEAPFFL does not normally purchase corporate bonds with callable features—except for standard par call options within three months of maturity (BoE 2020f; BoE 2020h). If a finance subsidiary wishes to participate in the program, the BoE normally requires the parent company to guarantee its securities (BoE 2020h). The BoE publishes a full list of eligible securities on its website (BoE 2021g).

The BoE attempts to avoid overinfluencing one sector or company by spreading corporate bond purchases across eligible issuers and sectors (BoE 2020h). The BoE tries to restrict CBPS assets to investment-grade bonds issued by companies that make “material contributions,” through employment or revenue generation, to the British economy (BoE 2020h, 6). The list of eligible issuers does not include firms that the BoE regulates—such as banks or insurance companies.

On June 4, 2020, the BoE expanded the list of eligible corporate debt to include bonds with three months to maturity par call features (BoE 2020f). Though the MPC does not explain the adjustment in its June 17 meeting minutes, it may have been to reduce debt loads (BoE MPC 2020c). An Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development report notes that callable bonds allow the issuer to redeem the bond before maturity, so issuers are incentivized to refinance during lower-interest-rate environments to reduce debt cost (Isaksson, Çelik, and Demirtaş 2019). At the same meeting, the MPC voted to increase its target stock of gilt purchases but not corporate bondsFThough the MPC did not have explicit language about the omission of corporate debt from its second round of COVID-19 asset purchases, the June 17 minutes offer details on high corporate credit demand, stabilization of credit conditions for firms, the UK government’s other corporate financing facilities, and already-indebted firms’ desires to seek other methods for raising capital (BoE MPC 2020c). At the same meeting, the MPC decided to slow the weekly volume of asset purchases because liquidity conditions improved and offered to raise the volume of weekly purchases if conditions worsened again. (BoE MPC 2020c).

On November 5, 2021, the BoE pledged to “green” the CBPS, reflecting the central bank’s secondary commitment to an economy-wide transition to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 (BoE 2021k). The BoE aimed to reduce the CBPS’s carbon footprint by:

- Setting portfolio targets on net emissions and weighted average carbon intensity;

- Limiting eligible issuers to companies who comply with UK climate governance measures and excluding debt issuances related to coal mining activities;

- Tilting purchases toward strong climate performers and away from weak performers, using scorecards that incorporate emissions data, reductions efforts, climate disclosure, and third-party verification of firms’ emissions targets; and

- Escalating eligibility requirements as data and metrics improve and divesting when company performance fails to meet the BoE’s climate standards.

Haircuts

1

There were no haircuts applicable to the APF.

Interest Rate

1

There were no interest rates applicable to the APF.

Fees

1

There were no fees applicable to the APF.

Term

1

There was no term applicable to the APF.

Other Conditions

1

There were no other restrictions applicable to the APF.

Regulatory Relief

1

There are no relevant regulatory changes directly applicable to the APF. In October 2017, the BoE’s PRA excluded central bank reserves from its calculation of banks’ leverage ratio, following a recommendation by the BoE’s Financial Policy Committee (BoE PRA 2017, 5). From their calculation of capital requirements, firms subject to the UK leverage ratio excluded deposit-matched central bank claims denominated in the same currency and the same or longer maturity (BoE PRA 2017, 5). The measure is meant to prevent the leverage ratio from interfering with any monetary policy action leading to an increase in central bank reserves (BoE PRA 2017).

International Cooperation

1

There was no international coordination applicable to the APF.

Duration

1

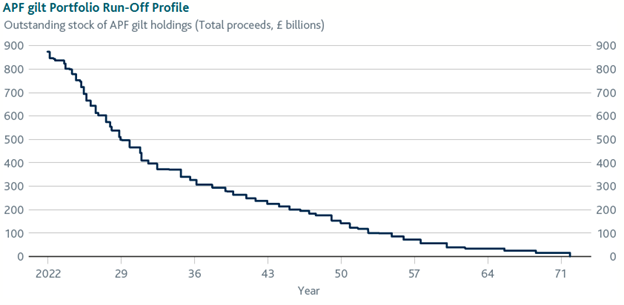

On February 2, 2022, the MPC voted unanimously to reduce its stock of gilt and corporate bond purchases by refraining from reinvesting maturing assets, and it pledged to fully unwind the CBPS via asset sales through the end of 2023 (BoE MPC 2022). At the same meeting, the MPC requested BoE staff to design a corporate bond sales program within three months and prior to the start of sales. Governor Bailey suggested that the BoE would only consider active sales of gilts once the Bank Rate has risen to at least 1% and that the BoE would keep open the possibility of future asset purchases if warranted by economic conditions (Bailey 2022). Through asset maturation alone, the BoE expects the APF’s gilt portfolio to decrease by GBP 70 billion in 2022 and 2023, an additional GBP 130 billion in 2024 and 2025, and the remainder by the end of 2071, as shown in Figure 4 (BoE MPC 2022).

Figure 4: Maturity Profile of the Stock of Gilts Held in the APF (in GBP billions)

At its February 2022 meeting, the MPC emphasized high 12-month inflation readings, low unemployment, and slow output growth (BoE MPC 2022). Prior to 2022, BoE officials suggested that any reduction in the APF would likely occur after the Bank Rate had been raised and market functioning had normalized (BoE MPC 2021). MPC minutes suggest that gilt and corporate bond markets had largely stabilized by mid-June 2020. On February 2, 2022, the MPC voted to raise the Bank Rate by 25 bps (BoE 2021i; BoE MPC 2020c; BoE MPC 2022). No matter the timing of unwinding, the MPC had vowed to stop reinvestment as its first step, providing a predictable and gradual path to the BoE’s balance sheet reduction (BoE MPC 2021).

At the onset of the asset purchases in March 2020, the MPC’s meeting minutes omitted language about potential dates for ending purchases or downsizing the BEAPFFL’s holdings, though the BoE pledged in June to coordinate any reduction in the APF with the DMO (Bailey 2020c; BoE MPC 2020b). When the MPC voted to increase the stock of purchases in June 2020, committee members expected to finish the purchases around the turn of the year (BoE MPC 2020c). After the MPC voted for a third increase to the APF in November 2020, they expected purchases to be completed around the end of 2021 (BoE MPC 2020d).

Key Program Documents

-

Bank of England (BoE). November 5, 2020. “What Is Quantitative Easing?”

Web page from the BoE that describes the form and function of quantitative easing in layman’s terms.

-

(BoE 2016b) Bank of England (BoE). October 3, 2016. “The Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility: APF Operating Procedures; Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme; Gilt Purchases.”

Earlier version of the APF operating procedures. This manual covers the program’s counterparties, Btender operations, descriptions of the Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme and gilt purchases, settlement procedures, and other purchase contingencies.

-

(BoE 2019a) Bank of England (BoE). July 2019. “Cash Transfers Between BEAPFF and HMT.”

Brief document describing the cash flows between BEAPFF, HMT, and the BoE. Variations in cash flows to/from the BEAPFF depend on a several macroeconomic variables and rates.

-

(BoE 2019b) Bank of England (BoE). December 9, 2019. “Governance of the Bank Including Matters Reserved to the Court.”

Document describing the BoE’s Court of Directors, including their responsibilities and formation.

-

(BoE 2020d) Bank of England (BoE). April 22, 2020. “Statement on Increase to APF Gilt Lending Limits.”

Document explaining the increase in the BoE’s lending limits to HMT’s Debt Management Office, an attempt to quell any frictions in primary gilt issuances and its associated markets.

-

(BoE 2020h) Bank of England (BoE). August 12, 2020. “The Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility: APF Operating Procedures; Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme; Gilt Purchases.”

Later version of the APF operating procedures. This manual covers the program’s counterparties, Btender operations, descriptions of the Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme and gilt purchases, settlement procedures, and other purchase contingencies.

-

(BoE 2021a) Bank of England (BoE). March 10, 2021. “Bank of England - Written Evidence (QEI0015) Quantitative Easing Inquiry.” House of Lords: Economic Affairs Committee.

Written description, in the BoE’s own words, of how and why it launched the APF in response to COVID-19. The BoE justifies its actions through assessments of gilt and corporate bond markets.

-

(BoE 2021d) Bank of England (BoE). June 24, 2021. “Monetary Policy.”

Web page describing how the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee makes monetary policy decisions.

-

(BoE 2021e) Bank of England (BoE). July 6, 2021. “Bank of England Market Operations Guide: Our Objectives.”

Explains how the BoE meets its institutional objectives through both traditional and unconventional monetary policy tools.

-

(BoE 2021f) Bank of England (BoE). July 6, 2021. “Bank of England Market Operations Guide: Our Tools.”

Description of the BoE’s tools and for what purposes the BoE would elect to use each.

-

(BoE 2021g) Bank of England (BoE). July 13, 2021. “Bank of England Market Operations Guide: Information for Participants.”

Web page containing links to the relevant information about the BoE’s various programs. The page is meant for prospective and current market participants.

-

(BoE 2021k) Bank of England (BoE). November 5, 2021. “Greening Our Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme (CBPS).”

Describes the BoE’s efforts to “green” its CBPS. The document covers objectives, tools, and strategies.

-

(BoE 2008) Bank of England (BoE). January 2008. “The Framework for the Bank of England’s Operations in the Sterling Money Markets.”

Legal framework of the BoE’s Sterling Money Markets Operations, which includes open market operations and its eligible instruments. The BoE had to purchase private sector securities through a subsidiary (APF) because the central bank was not otherwise able to purchase the securities under open market operations.

-

(BoE 2018) Bank of England (BoE). June 2018. “The MPC and the Bank’s Sterling Monetary Framework.”

This paper sets out a framework for engagement between the bank’s Executive and the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) about the bank’s Sterling Monetary Framework (SMF), in particular with regard to those operations that affect monetary conditions.

-

(BoE PRA 2017) Bank of England, Prudential Regulation Authority (BoE PRA). October 18, 2017. “Policy Statement, UK Leverage Ratio: Treatment of Claims on Central Banks.” PS21/17.

Describes the BoE PRA’s efforts to insulate followers of the PRA’s leverage ratios from the BoE’s asset purchases.

-

(DMO 2021) Her Majesty’s Treasury: Debt Management Office (DMO). March 8, 2021. “GEMM Guidebook: A Guide to the Roles of the DMO and Primary Dealers (GEMMs) in the UK Government Bond Market.”

Describes the role of the DMO and primary dealers in British government bond markets, including prerequisites to serve as a gilt-edged market maker (GEMM).

-

(FSA 2012) Financial Services Act 2012 (FSA). 2012.

Describes the actions that must be taken by the BoE, HMT, and other regulators during a financial crisis.

-

(HMT 2017) Her Majesty’s Treasury (HMT). October 2017. “Memorandum of Understanding on Resolution Planning and Financial Crisis Management.”

Describes the roles and responsibilities of HMT, the BoE, and other British financial regulators after the Global Financial Crisis.

-

(HMT/BoE/FSA 2006) Her Majesty’s Treasury, Bank of England, and Financial Services Authority (HMT/BoE/FSA). March 22, 2006. “Memorandum of Understanding between HM Treasury, the Bank of England and the Financial Services Authority.”

Describes the financial crisis responsibilities of the BoE, HMT, and other British regulators prior to the Global Financial Crisis.

-

(UK Gov 2021) United Kingdom Government (UK Gov). 2021. “Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited Filing History.”

Web page covering the APF’s filing history, which reveals who formed and owned the BoE subsidiary.

-

(Bailey 2022) Bailey, Andrew. February 3, 2022. “Letter from Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey to the Chancellor Rishi Sunak.”

Letter from Governor Bailey describing the BoE’s intent to cease reinvesting proceeds from assets through the APF. This document spells out the end of the APF, offers a maturity schedule, and describes how the BoE decided to bring the emergency actions to a close.

-

(Bailey 2020b) Bailey, Andrew. March 19, 2020. “Letter from Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey to Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak.”

Letter from Governor Bailey in which he requests an expansion of HMT’s indemnification by GBP 200 billion so that BoE can conduct asset purchases to stem the financial turbulence associated with the COVID-19 crisis.

-

(Bailey 2020c) Bailey, Andrew. June 18, 2020. “Letter from Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey to Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak.”

Governor Bailey requests an additional GBP 100 billion of HMT’s indemnification, bringing the total to GBP 745 billion. The letter describes existing authorizations; the use of APF for monetary policy; and governance, transparency, and accountability measures.

-

(Bailey 2020d) Bailey, Andrew. November 5, 2020. “Letter from Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey to Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak.”

Letter requesting an additional GBP 150 billion in HMT’s indemnity, bringing the total size of the APF to GBP 895 billion. The letter outlines existing authorizations; the use of the APF for monetary policy; and governance, transparency, and accountability measures.

-

(BoE 2016a) Bank of England (BoE). September 12, 2016. “Asset Purchase Facility Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme: Eligibility and Sectors.” Market notice.

Market notice describing the eligible issuers and sectoral distribution of the Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme.

-

(BoE 2020a) Bank of England (BoE). March 19, 2020. “Asset Purchase Facility (APF): Asset Purchases and TFSME – Market Notice 19 March 2020.”

Describes the actions taken by the Monetary Policy Committee after a special meeting on 19 March. The BoE first announces the COVID-19-era asset purchases through this market notice.

-

(BoE 2020b) Bank of England (BoE). June 18, 2020. “Asset Purchase Facility (APF): Gilt Purchases – Market Notice 18 June 2020.”

Describes the second increase of the APF in response to COVID-19, bringing BoE’s aggregate purchases to GBP 745 billion in 2020.

-

(BoE 2020c) Bank of England (BoE). April 2, 2020. “Asset Purchase Facility (APF): Additional Corporate Bond Purchases – Market Notice 2 April 2020.”

Market notice describing the purpose of the additional rounds of asset purchases taken in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

-

(BoE 2020e) Bank of England (BoE). May 1, 2020. “Asset Purchase Facility (APF): Additional Corporate Bond Purchases – Market Notice 1 May 2020.”

Describes the operation of the BoE’s Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme. The market notice describes eligibility and purchase parameters.

-

(BoE 2020f) Bank of England (BoE). June 5, 2020. “Asset Purchase Facility (APF): Pricing of CBPS Eligible Securities – Market Notice 5 June 2020.”

Clarifies the pricing of CBPS eligible securities.

-

(BoE 2021i) Bank of England (BoE). August 18, 2021. “Data: Weekly Purchases of Gilts in the Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility Operations (in Sterling Millions).” Dataset.

Describes the BoE’s weekly purchases of gilts through the APF.

-

Bank of England (BoE). August 25, 2021. “Data: Quantity of Assets Purchased by the Creation of Central Bank Reserves on a Settled Basis (in Sterling Millions).” Dataset.

Describes the assets purchased by the BoE through the APF, financed by the creation of central bank reserves.

-

(BoE 2022) Bank of England (BoE). August 24, 2022. “Bank of England Market Operations Guide: Results and Usage Data.” Dataset.

Web page describing the usage for all the BoE’s programs.

-

(BoE/DMO 2009) Bank of England and Her Majesty’s Treasury: Debt Management Office (BoE/DMO). August 6, 2009. “Joint Bank-DMO Statement on Gilt Lending.”

States the financial relationship between the BoE’s subsidiary (BEAPFFL) and HMT’s Debt Management Office (DMO). The purpose of on-lending to the DMO is to prevent gilt market frictions stemming from BoE’s asset purchases.

-

(BoE MPC 2008) Bank of England, Monetary Policy Committee (BoE MPC). October 22, 2008. “Minutes of the Special Monetary Policy Committee Meeting Held on 8 October 2008.”

Describes the BoE’s off-cycle emergency meeting on October 8, 2008, in response to the Global Financial Crisis.

-

(BoE MPC 2020a) Bank of England, Monetary Policy Committee (BoE MPC). March 13, 2020. “Minutes of the Special Monetary Policy Committee Meeting Ending on 10 March 2020.”

Describes the BoE’s preliminary assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on the British economy. The MPC had not yet decided to purchase assets to respond to COVID-19.

-

(BoE MPC 2020b) Bank of England, Monetary Policy Committee (BoE MPC). March 26, 2020. “Minutes of the Special Monetary Policy Committee Meeting on 19 March 2020 and the Monetary Policy Committee Meeting Ending on 25 March 2020.”

Describes the macroeconomic conditions that warranted the expansion of BoE’s APF. The meeting minutes describe the central bank’s information set and unanimous vote in favor of quantitative easing.

-

(BoE MPC 2020c) Bank of England, Monetary Policy Committee (BoE MPC). June 18, 2020. “Monetary Policy Summary and Minutes of the Monetary Policy Committee Meeting Ending on 17 June 2020.”

Describes the BoE’s decision to increase the APF by GBP 100 million.

-

(BoE MPC 2020d) Bank of England, Monetary Policy Committee (BoE MPC). November 5, 2020. “Monetary Policy Summary and Minutes of the Monetary Policy Committee Meeting Ending on 4 November 2020.”

Describes BoE MPC’s vote to increase government bond purchases by GBP 150 billion, bringing to the total size of the APF’s gilt holdings to GBP 875 billion.

-

(BoE MPC 2022) Bank of England, Monetary Policy Committee (BoE MPC). February 3, 2022. “Monetary Policy Summary and Minutes of the Monetary Policy Committee Meeting Ending on 2 February 2022.”

Describes the BoE’s decision to stop reinvesting proceeds from the APF into more securities. These minutes amount to the beginning of the end of the APF.

-

(Darling 2009a) Darling, Alistair. January 19, 2009. Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling’s Address to the House of Commons. House of Commons Hansard Archives.

Exhibits Alistair Darling’s announcement of the Asset Purchase Facility, for the first time in early 2009.

-

(Darling 2009b) Darling, Alistair. January 29, 2009. “Letter from Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling to Bank of England Governor Mervyn King (29 January 2009).”

Describes HMT’s initial offer to indemnify the BoE’s emergency asset purchases in 2009 through the issuance of T-bills.

-

(Darling 2009c) Darling, Alistair. March 3, 2009. “Letter from Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling to Bank of England Governor Mervyn King.”

Describes the permission granted by Darling to King to enable the BoE to use the APF for monetary policy purposes, in addition to emergency market purposes.

-

(Darling 2021) Darling, Alistair. March 2, 2021. Transcript of Uncorrected Oral Evidence: Quantitative Easing. House of Lords: Select Committee on Economic Affairs. Evidence Session No. 8, questions 68-85.

Describes Alistair Darling’s view on the origin and purpose of the BoE’s APF.

-

(DMO n.d.) Her Majesty’s Treasury: Debt Management Office (DMO). n.d. “UK Debt Management Office (DMO): About DMO.” Accessed July 15, 2021.

Describes the history and general operations of the UK’s DMO.

-

(HMT 2009) Her Majesty’s Treasury (HMT). January 19, 2009. “Statement on Financial Intervention to Support Lending in the Economy.”

Captures the first public mention of the APF and the BoE’s imminent asset purchases in January 2009.

-

(HMT 2020) Her Majesty’s Treasury (HMT). March 11, 2020. “Budget 2020: Delivering on Our Promises to the British People.”

Describes HMT’s budgetary vision for the year 2020. This budget includes limited estimates of pandemic-induced spending.

-

(King 2009) King, Mervyn. February 17, 2009. “Letter from Bank of England Governor Mervyn King to Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling.”

Outlines Governor King’s request to incorporate the APF into the BoE’s monetary policy tool kit.

-

(King 2012) King, Mervyn. June 26, 2012. Oral Evidence Taken Before the Treasury Committee: Bank of England May 2012 Inflation Report. HC 407 House of Commons.

Captures Governor King’s account of how and why the APF formed in the first place.

-

(Sunak 2020a) Sunak, Rishi. March 17, 2020. “Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak on COVID-19 Response.” Speech.

Describes the measures taken by HMT and the BoE to stem the economic damage of the COVID-19 crisis.

-

(Sunak 2020b) Sunak, Rishi. Letter to Andrew Bailey. March 19, 2020. “Extension of Asset Purchase Facility.” Letter to Andrew Bailey.

Describes HMT’s willingness to increase its indemnity of the APF during the COVID-19 crisis.

-

(Sunak 2020c) Sunak, Rishi. Letter to Andrew Bailey. June 18, 2020. “Extension of Asset Purchase Facility.” Letter to Andrew Bailey.

Describes HMT’s willingness to increase its indemnity of the APF during the COVID-19 crisis.

-

(Sunak 2020d) Sunak, Rishi. Letter to Andrew Bailey. November 5, 2020. “Extension of Asset Purchase Facility.”

Describes HMT’s willingness to increase its indemnity of the APF during the COVID-19 crisis.

-

(Tucker 2009) Tucker, Paul. May 27, 2009. “The Repertoire of Official Sector Interventions in the Financial System – Last Resort Lending, Market-Making, and Capital.” Remarks presented at the Bank of Japan 2009 International Conference, “Financial System and Monetary Policy: Implementation,” Tokyo, May 27.

Describes the role of the BoE as market maker of last resort, including for gilt and corporate bond markets.

-

(UK Gov 2020) United Kingdom Government (UK Gov). March 20, 2020. “Chancellor Announces Workers’ Support Package.”

Describes measures taken by the British government to support British workers.

-

(Ainger and Ritchie 2020) Ainger, John, and Greg Ritchie. March 10, 2020. “Britain Seen Announcing Biggest Bond Deluge in Nearly a Decade.” Bloomberg Markets.

Article describing the UK’s bond issuance, which was set to surge to the highest level in nine years—an excess supply of gilts that eventually led to the malfunctioning of the gilt market. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government was expected to unveil a significant increase in budget spending.

-

(Aldrick 2020a) Aldrick, Philip. April 30, 2020. “Bank of England Rode to Government’s Rescue as Gilt Markets Froze.” The Times.

Article describing the Debt Management Office’s struggles to offload gilts on the morning of March 19, 2020.

-

(Aldrick 2020b) Aldrick, Philip. April 30, 2020. “The Day the Financial World Stood Still.” The Times.

Article describing the gilt market malfunctioning in March 2020 due to the gilt-edged market makers not knowing who would purchase government debt in unexpectedly large quantities.

-

(Bailey 2020a) Bailey, Andrew. June 22, 2020. “Coronavirus: Bank of England Rescued Government, Reveals Governor.” Interview by reporter Ed Conway, Sky News.

Interview between Governor Bailey and a reporter from Sky News. Bailey explains the BoE’s emergency actions taken in response to the COVID-19 crisis, and he rejects any claim that the BoE’s asset purchases were motivated by sudden, high fiscal deficits.

-

(Bosley 2020) Bosley, Catherine. June 30, 2020. “Government Debts May Hold Monetary Policy Hostage, BIS Warns.” Bloomberg L.P.

Relays one Bank for International Settlements researcher’s concerns about the price of costly government spending and potential knock-on effects on central bank decision-making.

-

(Darling 2011) Darling, Alistair. 2011. Back from the Brink: 1000 Days at Number 11. London: Atlantic Books.

Covers Alistair Darling’s emergency decisions as the chancellor of the Exchequer. This is a memoir about his private perspective and experience at the helm of the UK economy during the Global Financial Crisis.

-

(Douglas 2020) Douglas, Jason. March 19, 2020. “Bank of England Cuts Rates Further, Restarts Bond Purchases.” Wall Street Journal.

Describes how the BoE cut its benchmark interest rate to a record low and said it would buy $232 billion of UK government bonds, in the latest push by a major central bank to combat the economic damage from the coronavirus.

-

(Giles and Tucker 2020) Giles, Chris, and Paul Tucker. June 25, 2020. “Monetary Policy Tools in the COVID-19 Crisis.” Webinar by the Royal Economic Society.

Interview between Chris Giles and Paul Tucker in which Tucker asserts that the BoE’s asset purchases in 2020 exceeded any classic “lender of last resort” operation.

-

(Giles, Parker, and Payne 2020) Giles, Chris, George Parker, and Sebastian Payne. March 19, 2020. “Sunak to Launch Massive Rescue Package for Stricken UK Companies.” Financial Times.

Describes how the BoE cuts rates to 0.1% and launches GBP 200 billion bond-buying program.

-

(Allen 2017) Allen, William A. July 31, 2017. “Quantitative Easing the Independence of the Bank of England.” National Institute Economic Review, 241, no. 1: R65-R69.

This paper from a former BoE official argues that the BoE’s asset purchases amounted to the monetization of fiscal deficits. The author argues that the BoE endured governance issues and operational limitations stemming from its entanglement with Her Majesty’s Treasury.

-

(Bailey et al. 2020) Bailey, Andrew, Jonathan Bridges, Josh Jones, and Aakash Mankodi. August 27, 2020. “The Central Bank Balance Sheet as a Policy Tool: Past, Present and Future.” Presentation at the “Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium” conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Paper describing the design of the BoE’s asset purchases. The authors specifically cover the purchase pace, arguing that the front-loaded purchases may have prevented a counterfactual downward spiral in market illiquidity.

-

(Borio and Zabai 2018) Borio, Claudio and Zabai, Anna. May 25, 2018. “Chapter 20: Unconventional Monetary Policies: a Re-appraisal.” From Research Handbook on Central Banking, edited by Peter Cont-Brown and Rosa Maria Lastra. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Describes large-scale asset purchase programs throughout modern history.

-

(Czech et al. 2021) Czech, Robert, Bernat Gual-Ricart, Joshua Lillis, Jack Worlidge. June 25, 2021. “The Role of Non-bank Financial Intermediaries in the ‘Dash for Cash’ In Sterling Markets.” Bank of England Financial Stability Paper, no. 47.

Covers the causes and consequences of the “dash for cash” in the United Kingdom.

-

(Fisher 2010) Fisher, Paul. February 18, 2010. “The Corporate Sector and the Bank of England’s Asset Purchases.” Speech for the Association of Corporate Treasurers Winter Paper 2010 in London, England. Bank for International Settlements.

Address by Paul Fisher on the origin, purpose, and effects of the BoE’s APF.

-

(Hauser 2020) Hauser, Andrew. June 5, 2020. “Seven Moments in Spring: Covid-19, Financial Markets and the Bank of England’s Balance Sheet Operations.” Bank of England. Speech given to Bloomberg in London, England.

Speech describing the effects of the BoE’s market intervention on gilt and corporate bond activity.

-

(Isaksson, Çelik, and Demirtaş 2019) Isaksson, Mats, Serdar Çelik, and Gül Demirtaş. February 25, 2019. “Corporate Bond Markets in a Time of Unconventional Monetary Policy.” OECD Capital Market Series.

Describes the behavior of corporate bond markets in low-interest-rate environments.

-

(Lawson and Feldberg 2020) Lawson, Aidan, and Greg Feldberg. 2020. “Monetization of Fiscal Deficits and COVID-19: A Primer.” Journal of Financial Crises 2, no. 4: 1–35.

Describes the monetization of fiscal deficits during the COVID-19 crisis.

-

(McLaren and Smith 2013) McLaren, Nick, and Tom Smith. March 14, 2013. “The Profile of Cash Transfers Between the Asset Purchase Facility and Her Majesty’s Treasury.” Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 53, no. 1: 29–37.

Describes the profile of cash transfers between the BoE, its subsidiary (BEAPFFL), and HMT, in relation to the BoE’s large-scale asset purchases. The paper describes the operations and origins of BoE’s asset purchases and identifies sources of fluctuation in the asset purchases.

-

(Metrick and Rhee 2018) Metrick, Andrew, and June Rhee. September 14, 2018. “Regulatory Reform.” Annual Review of Financial Economics 2018, no. 10: 153–72.

Describes the steps taken by British authorities to correct the financial regulatory landscape after the Global Financial Crisis.

-

(Ramsden 2020) Ramsden, Dave. October 21, 2020. “The Monetary Policy Toolbox in the UK.” Speech given to Society of Professional Economists. Bank of England.

Describes the “positive spillover effects” of the BoE’s COVID-19-era asset purchases.

-

(Rosengren 2019) Rosengren, Eric. July 19, 2019. “Central Bank Independence: What It Is, What It Isn’t – and the Importance of Accountability.” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Describes the inflationary threats of central bank dependence.

-

(Salib and Skinner 2020) Salib, Michael, and Christina Parajon Skinner. April 2020. “Executive Override of Central Banks: A Comparison of the Legal Frameworks in the United States and the United Kingdom.” Georgetown Law Journal 108, no. 4: 76.

Describes the legal frameworks that allow federal governments to override central banks and steer their decisions.

-

(Smith 2020) Smith, Ariel. 2020. “The United Kingdom’s Asset Purchase Program (U.K. GFC).” Journal of Financial Crises 2, no. 3: 437–58.

Describes the BoE’s original initiation of the APF, known as the “Asset Purchase Program,” in response to the Global Financial Crisis.

-

(BoE 2020g) Bank of England (BoE). June 18, 2020. “Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited Annual Report and Accounts: 1 March 2019–29 February 2020.”

Describes the APF’s activities from 2019 to 2020. The report includes various financial statements and explains the APF’s activities, governance arrangements, and disclosure requirements. The notes to the financial statement describe the APF balance sheet according to maturity, sectoral distribution, credit risk, and other analytical lenses.

-

(BoE 2021b) Bank of England (BoE). May 26, 2021. “Bank of England Annual Report and Accounts 1 March 2020–28 February 2021.”

Describes the BoE’s annual activities from 2020 to 2021, and the report includes its various financial statements.

-

(BoE 2021c) Bank of England (BoE). June 17, 2021. “Bank of England Asset Purchase Facility Fund Limited Annual Report and Accounts: 1 March 2020–28 February 2021.”

Describes the APF’s activities from 2020 to 2021. The report includes various financial statements and explains the APF’s activities, governance arrangements, and disclosure requirements. The notes to the financial statement describe the APF balance sheet according to maturity, sectoral distribution, credit risk, and other analytical lenses.

-

(BoE 2021h) Bank of England (BoE). July 26, 2021. “Asset Purchase Facility Quarterly Report–2021 Q2.”

Contains headline figures for the APF’s activity in Q2 2021.

-

(BoE FPC 2020) Bank of England, Financial Policy Committee (BoE FPC). May 6, 2020. “Interim Financial Stability Report.”

Describes the financial stability conditions across the United Kingdom during the outbreak of COVID-19.

-

(BoE IEO 2021) Bank of England, Independent Evaluation Office (BoE IEO). January 13, 2021. “IEO Evaluation of the Bank of England’s Approach to Quantitative Easing.”