Reserve Requirements

Thailand: Reserve Requirements, AFC

Purpose

To “help improve money supply in the financial system and solve liquidity problems many financial institutions have been facing” (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997)

Key Terms

-

Range of RR Ratio (RRR) Peak-to-Trough7%–6%

-

RRR Increase PeriodAugust 1995 (commercial banks) April 1996 (finance companies)

-

RRR Decrease PeriodDomestic liabilities: September 8, 1997 Nonresident liabilities: July 1998

-

Legal AuthorityCommercial Banking Act and Finance Company Act

-

Interest/Remuneration on ReservesDeposits with the BOT paid no interest; however, companies could meet most of their RR with interest-bearing assets

-

Notable FeaturesThe BOT repeatedly expanded the list of liquid assets that healthy banks could use to satisfy the domestic RR—to support the provision of liquidity to illiquid or restructured financial institutions, and to fund more than 20 government agencies and state enterprises

-

OutcomesExpected to release THB 51.6 billion (USD 1.52 billion) in liquidity

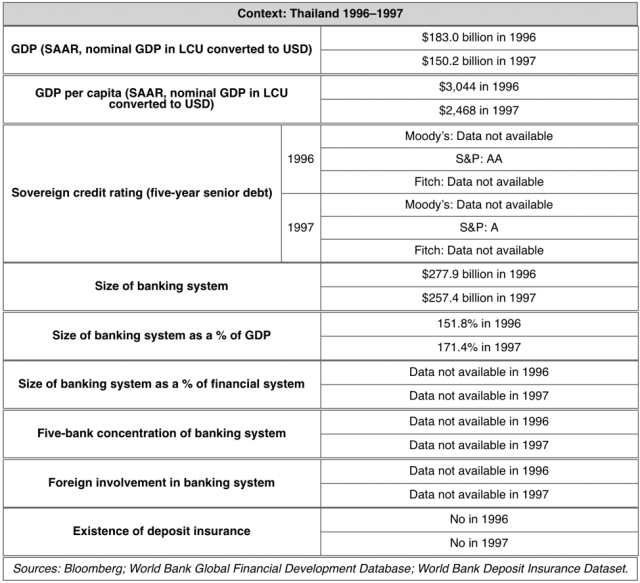

Following years of growth, the Thai economy began showing confidence-busting signs in 1996, including a liquidity crunch. In May 1997, the Bank of Thailand (BOT) announced that it would expand the list of short-term assets that banks and finance companies could use to satisfy the BOT’s liquidity reserve requirement, including obligations of the Financial Institution Development Fund (FIDF), which provided liquidity support to illiquid financial institutions. In the summer of 1997, the BOT suspended the operations of 58 finance companies and floated the Thai baht (THB), unleashing the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC). Tight liquidity conditions continued and, in September 1997, the BOT cut the RR on domestic deposits from 7% to 6%. Thai officials said at the time that the lower RRR would result in an increase of THB 51.6 billion (USD 1.52 billion) in cash held by banks and finance companies. Companies could satisfy this reserve requirement by holding deposits at the BOT or by holding public securities and bonds. The BOT repeatedly expanded the list of eligible reserve assets. In July 1998, the BOT allowed holdings of the debt of banks and finance companies that the government had consolidated to satisify the reserve requirement. The BOT made further changes to the RR in 1998 and 1999, redefining “short-term foreign lending” and lowering the portion of the RR that commercial banks were required to deposit with the BOT. In April 1999, to support Thailand’s economic recovery, the BOT added loans to the Export-Import Bank of Thailand to the list of eligible reserve assets. Contemporaneous observers were skeptical of the BOT’s reserve requirement policy, noting that it was insufficient to reduce liquidity concerns and carried risks.

During the early 1990s, the Thai government liberalized capital inflows and encouraged banks to borrow abroad to finance domestic activities through lending facilities called Bangkok International Banking Facilities (BIBFs) (Haksar and Giorgianni 2000; Santiprabhob 2003). At the time, Thailand maintained a fixed exchange rate between the Thai baht (THB) and the US dollar (USD) (Santiprabhob 2003).

In 1995, the Bank of Thailand (BOT) took several measures to “slow credit growth, restrict short-term capital inflows, and reduce the inflationary impact of these inflows” (Sharma 2013, 79). Among those measures, the BOT required that commercial banks hold liquid reserves—in BOT deposits, government securities, or vault cash—equal to at least 7% of their nonresident baht deposits, with a maturity under one year (Sharma 2013). Since 1974, the Bank of Thailand had held commercial banks to a 7% reserve requirement ratio (RRR) for their domestic deposits (Dasri 1990). But this requirement had not applied to foreign deposits, a discrepancy that had encouraged banks to raise funds from abroad (BOT 1997g). In April 1996, the BOT extended the 7% reserve requirement to nonresident baht deposits of finance companies as well (Sharma 2013).

Inside Thailand, large amounts of portfolio growth made the country’s financial sector vulnerable to a sudden decline in investor confidence. In 1996, the midsize Bangkok Bank of Commerce collapsed, followed by a decline in exports, a slowdown in bank profit growth, and a slump in real estate prices. The burst real-estate bubble proved significant because finance companies—Thai nonbank lenders that took deposits—had concentrated exposures to real estate and consumer loans (BOT 2003a; Nabi and Shivakumar 2001).

During the first quarter of 1997, concerns about the capital adequacy and liquidity of Thailand’s finance companies and small banks led to depositor runs. The BOT tasked the Financial Institution Development Fund (FIDF) with providing liquidity support to illiquid financial institutions (Santiprabhob 2003).

The BOT also revised its RR policies to help alleviate the credit crunch. On May 30, 1997, the BOT began allowing banks to use loans to the FIDF to satisfy the domestic RR, which remained at 7%. This change came into effect on June 24, 1997, for both financial institutions and commercial banks. It created an avenue for relatively healthy institutions to meet the RR. It also helped the FIDF fund its growing liquidity support for troubled finance companies, which ultimately cost the government at least THB 244 billion (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997b; Santiprabhob 2003; Sutham 1997).

In June 1997, the BOT suspended the operations of 16 finance companies, because of capital-adequacy concerns. Among these was Finance One, one of Thailand’s largest finance companies (Santiprabhob 2003).

At the same time, between November 1996 and July 1997, currency speculators attacked the baht three times, and the BOT defended it three times, initially ruling out devaluation (Nabi and Shivakumar 2001). The BOT accumulated large forward positions that whittled its international reserves from more than USD 39 billion in November 1996 to just over USD 1 billion in July 1997 (BOT 1998d). Given these circumstances and deteriorating confidence, on July 2, 1997, the BOT abandoned the baht’s fixed exchange rate and floated it. The subsequent depreciation of the baht marked the beginning of the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) (Nabi and Shivakumar 2001). Following this depreciation, Thailand in August 1997 entered into a 34-month Stand-By Arrangement (SBA) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Gov’t of Thailand 1997).

Also in August 1997, the BOT suspended 42 additional finance companies. With these suspensions, the BOT attempted to end deposit runs, bring the FIDF’s liquidity support under control, restore confidence, and eliminate market distortions (Santiprabhob 2003).

In spite of these actions, Thai financial institutions continued to face a liquidity crunch (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997). To ease these conditions, on September 8, 1997, the BOT cut the domestic RR from 7% to 6% (BOT 1997c; BOT 1997d). For financial institutions, this change came into effect on September 12, 1997, and was calculated weekly, as had been the case previously (BOT 1997c). For commercial banks, the change came into effect on September 8, 1997, and was calculated fortnightly, as had been the case prior to the change (BOT 1997d). The breakdown of the required reserves for finance companies and commercial banks also differed (BOT 1997e; BOT 1997f). Thai officials expected the relaxed reserve requirements to increase liquidity by THB 51.6 billion (USD 1.52 billion) (Reuters 1997b; AFP 1997).FPer Bloomberg, on September 8, 1997, USD 1 = THB 33.9. Different news outlets, using different exchange rates for the day, estimated that the change would free between USD 875 million and USD 1.55 billion (AFP 1997; Bardacke 1997). That same month, Thai officials also announced a blanket guarantee of the deposits of banks and finance companies. They said that the FIDF had lent more than THB 800 billion to struggling finance companies (BOT 2003b; BOT 2009; Santiprabhob 2003).

In October 1997, the government formalized the Financial Sector Restructuring Agency (FRA), which reviewed the viability of the 58 suspended finance companies. Ultimately, in December 1997, the FRA decided that only two institutions could resume their operations (Santiprabhob 2003).

Meanwhile, the government began to consolidate failed commercial banks into new public entities. Krung Thai Bank (KTB) and Krung Thai Thanakit Finance Company (KTT) absorbed several formerly private entities and took over their existing liabilities (Santiprabhob 2003).

On July 6, 1998, the BOT announced further changes to the reserve requirements. KTB and KTT debt became eligible for the RRR (BOT 1998b; BOT 1998a; Santiprabhob 2003). For both finance companies and commercial banks, this change came into effect on July 8, 1998 (BOT 1998a; BOT 1998b).

Later in July 1998, the BOT brought the reserve requirements for nonresident deposits and foreign borrowing into line with its domestic reserve requirements on bank deposits, dropping the RRR to 6% (BOT 1999e). Finance companies, starting on July 31, 1998, were required to hold 0.5% of deposits and foreign borrowing with the BOT and 4.5% in eligible securities. Commercial banks and the BIBFs, beginning on August 8, 1998, were required to hold 2% of their deposits and foreign borrowing with the BOT and 2.5% in eligible securities (BOT 1998c).

In 1999, as the Thai economy began to stabilize, the BOT adopted further changes to the RR (BOT 2000; World Bank 1999). On April 5, 1999, the BOT lowered the portion of the RRR that it required commercial banks to deposit with the BOT from 2% to 1%. The BOT also introduced procedures to maintain liquidity in commercial banks, such as allowing excess reserves deposited at the BOT to carry over to the next fortnightly period and allowing commercial banks that missed the RRR to make up the shortfall during the next RRR calculation period. These changes were meant to reduce the cost to banks, given that reserves were unremunerated (BOT 2000). These changes came into effect on April 23, 1999 (BOT 1999a).

In November 1998, the BOT announced a list of 21 government agencies and state-owned enterprises whose debt or bonds commercial banks could use to meet the RRR. In April 1999, it added the Export-Import Bank of Thailand to that list (BOT 1999c).

Some scholars have said that the BOT’s RR policy in the years leading up to the AFC was “not very effective” (Sharma 2013, 80). The BOT’s decisions in 1995 and 1996 to increase the RR on nonresident baht deposits to 7%, in line with the longstanding RR on domestic deposits, reduced the profitability of BIBF transactions and removed the incentive for banks and finance companies to borrow overseas. BIBF transactions declined between 1996 and 1997. However, the BOT’s actions did not succeed in stemming short-term capital inflows in those pre-crisis years (Sharma 2013).

Following Thailand’s decision to cut the RRR on domestic deposits from 7% to 6% in September 1997, analysts argued that the decision would free up some liquidity but would likely be insufficient to bring down interbank lending rates (Amorn 1997). On the day the policy was announced, the market showed little reaction, with the baht weaker and the interbank lending rate only slightly changed (Reuters 1997a).

The BOT changed the RR for commercial banks in 1999, requiring them to deposit 1% of their deposits and short-term borrowing with the BOT, as opposed to 2%. The BOT noted that this change was meant to reduce the cost to commercial banks and the BIBFs, given that their deposits were unremunerated, and could use the additional 1% in other eligible reserve assets. The BOT also reported that the change to the cash RR had the effect of reducing the demand for the monetary base by THB 46 billion. The BOT absorbed the extra liquidity, and it said that the monetary base subsequently stabilized (BOT 2000).

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

1

Following years of substantial capital inflows, Thailand began to show confidence-busting signs in 1996, when the midsize Bangkok Bank of Commerce failed (Nabi and Shivakumar 2001). Thai economic conditions continued to deteriorate following this failure, and by the first quarter of 1997, Thai institutions faced both a liquidity shortage and capital-adequacy concerns. The Bank of Thailand (BOT) charged the Financial Institutions Development Fund (FIDF) to provide liquidity support to illiquid institutions (Santiprabhob 2003). To further provide liquidity support, the BOT allowed relatively healthy commercial banks and other finance companies to use their holdings of FIDF debt instruments, or other debt instruments guaranteed by the FIDF, to satisfy a portion of their 7% reserve requirement (RR) (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997b). “Eligible reserve assets also included government liabilities, and bonds or debt issued by certain state-owned enterprises, government agencies, or the Industrial Finance Corporation of Thailand” (Sutham 1997). In the summer of 1997, the BOT suspended the operations of 58 finance companies and floated the baht (Nabi and Shivakumar 2001).

In September, as the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) spread, the BOT cut the RRR on domestic deposits for finance companies and commercial banks to 6% to promote liquidity (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997; BOT 1997c; BOT 1997d). This change, the BOT estimated, would result in an increase of THB 51.6 billion in cash held by banks and finance companies (AFP 1997; Reuters 1997b).

Throughout 1998, economic conditions worsened, and the Thai economy contracted 8% (BOT 1999e). The BOT adopted further changes to the RR to aid banks during this turbulence. In July 1998, the BOT allowed financial and commercial institutions to use their holdings of the debt of KTB and KTT—two state-owned financial institutions resulting from the merger of failed Thai banks and finance companies—to satisfy the RR (BOT 1998a; BOT 1998b). That same month, the BOT brought the RR for nonresident deposits and foreign borrowing into line with its domestic RR on bank deposits, dropping the RR to 6% (BOT 1999e).

Part of a Package

1

After allowing institutions to use FIDF liabilities to meet their RR, in June 1997, the BOT suspended the operations of 16 finance companies (Santiprabhob 2003). A month later, after fighting off several speculative attacks, the BOT floated the baht in July 1997, leading to financial deterioration and forcing Thailand to enter into a 34-month Stand-By Arrangement (SBA) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Gov’t of Thailand 1997; Nabi and Shivakumar 2001). At the same time, the BOT suspended another 42 finance companies, aiming to stop bank runs, control liquidity, restore market confidence, and eliminate market distortions (Santiprabhob 2003).

Thai institutions continued to face deteriorating conditions even after these measures, including a liquidity shortage, which prompted the BOT to cut its RR to 6% in September 1997 (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997). The same day this was announced, the government communicated that the 58 suspended institutions would be required to raise their risk-asset-to-capital ratio to 15% (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997). Officials also announced that exporters could only hold dollar receivables for 120 days before converting them into baht, a decrease from 180 days (Bardacke 1997; Reuters 1997b).

By October 1997, the government formalized the Financial Sector Restructuring Agency (FRA) to examine the viability of the 58 suspended institutions, only two of which would reopen. The government consolidated failed entities into the KTB and the KTT (Santiprabhob 2003). In July 1998, the BOT said that it would accept KTB and KTT debt to fulfill the RR (BOT 1998a; BOT 1998b). Revised capital-adequacy rules accompanied this change (BOT 1998a; BOT 1998b).

Thai officials, in August 1998, announced the creation of the Thai Capital Support Facilities to restore solvency and confidence to the Thai system (Kulam 2020; Santiprabhob 2003).

Legal Authority

1

The BOT Act established the BOT as Thailand’s central bank (BOT Act [1985] 1942). The Commercial Banking Act, passed in 1962, set out the regulations governing commercial banks in Thailand (Commercial Banking Act 1962, preamble). Pursuant to Section 11 of the Commercial Banking Act, the BOT could require that commercial banks held certain liquid assets as it saw fit (Commercial Banking Act 1962, sections 11 ter-11 quinque). During the AFC, changes to the liquidity rules governing commercial banks were made in accordance with this provision. The Commercial Banking Act required the BOT to publish changes to these liquidity rules and required that commercial banks submit information to the BOT (Commercial Banking Act 1962, section 13, 15).

The Financial Company Act, originally passed in 1979, governed finance companies, securities businesses, and mortgage lenders (known as credit fonciers) (Finance Company Act 1979, preamble). Pursuant to section 28 of the Financial Company Act, the BOT could require finance companies to maintain certain liquid assets and could set the ratio for such assets (Finance Company Act 1979). Changes to the liquidity rules governing finance companies were thus made according to this provision. The Financial Company Act also required that finance companies submit information to the BOT and extended many of the provisions governing financial institutions to mortgage lenders, including those governing liquidity requirements (Finance Company Act 1979, sections 23, 56).

Administration

1

Pursuant to Thai law, the BOT could require commercial banks and credit institutions to maintain specific liquid assets at a given ratio (Commercial Banking Act 1962, section 11; Finance Company Act 1979, section 28). Commercial banks were required to submit information weekly to the BOT, including information related to banks’ assets (BOT Act [1985] 1942, section 33). Commercial banks also reported information to the BOT on a monthly basis (Commercial Banking Act 1962, section 15). Finance companies were also required to submit information to the BOT (Finance Company Act 1979, section 23).

From the sources consulted, it is unclear which specific BOT body decided upon the RR.

Governance

1

It is unclear how the BOT set its RR or how the BOT oversaw such changes. However, it is likely that a team in the BOT’s monetary stability group set the RRR, under the supervision of a governor and deputy-governor (BOT 2000, 123). When the BOT changed its liquidity rules, it needed to do so per the BOT’s rules, and then it was required to receive the minister of finance’s approval (Commercial Banking Act 1962, section 11 quinque). For instance, both the minister of finance and the governor of the BOT announced the RR changes in September 1997 (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997; AFP 1997).

The BOT would publish these changes in the Government Gazette (Commercial Banking Act 1962, section 11 quinque). Normally, if the BOT increased its RR, the requirement would come into effect 15 days after its publication in the Government Gazette; however, with the minister of finance’s approval, the rule could come into effect at the end of a given day, circumventing this 15-day grace period (Commercial Banking Act 1962, section 11 quinque, sex).

Thailand’s minister of finance exercised general supervisory powers over the BOT (BOT Act [1985] 1942, section 14). A court of directors, which included the governor of the BOT, the deputy-governor of the BOT, and at least five other members, governed the BOT (BOT Act [1985] 1942, section 15). The governor and the deputy-governor managed the day-to-day affairs of the BOT (BOT Act [1985] 1942, section 16). If the governor disagreed with the court of director’s majority decision, the minister of finance would decide the matter in question (BOT Act [1985] 1942, section 17).

Communication

1

The BOT announced changes to its RR through circulars, which were published. Thailand’s finance minister, Thanong Bidaya, and the BOT governor, Chaiyawat Wibulswasdi, announced the RR changes adopted on September 8, 1997. Thanong said that, by cutting the RR from 7% to 6%, liquidity conditions would likely loosen, helping institutions that faced liquidity shortages (AFP 1997; AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997).

The BOT also used its annual reports to communicate the purpose of its RR changes. In 1997, the BOT noted that it had raised the RR against foreign short-term borrowing before the crisis to eliminate the incentive for commercial banks to borrow from abroad in “massive amounts” (BOT 1997g, 37). In 1999, the BOT explained the reasoning behind later RR alterations, which were then meant to reduce the cost on banks and to comply with international standards (BOT 2000).

Assets Qualifying as Reserves

1

Before the Asian Financial Crisis, the domestic RR for both commercial banks and finance companies was 7% (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997b). However, eligible reservable assets differed for the two types of companies.

- Commercial banks were required to deposit 2% of this 7% with the BOT. Banks also had to hold 2.5% of the 7% in unencumbered government assets (BOT 1997b).FUnencumbered government assets included treasury bills, government bonds, debt instruments guaranteed by the Ministry of Finance, debt instruments issued by the FIDF, debt instruments or debentures guaranteed (as to principal and interest) by the FIDF, and/or debentures or bonds issued by certain state-owned enterprises, government agencies, or the Industrial Finance Corporation of Thailand (BOT 1997e; Sutham 1997).

- Finance companies were required to hold 0.5% of the 7% as a cash deposit with the BOT (BOT 1997a). They were required to maintain 5.5% of the RRR in unencumbered government assets (BOT 1997a).

Finance companies and commercial banks, once these requirements were met, could deposit the rest with the BOT or hold additional eligible deposits, securities, or bonds (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997b).

In May 1997, the BOT expanded the list of unencumbered assets that banks and financial companies could use to fulfill the domestic RRR, allowing institutions to use loans to the FIDF to satisfy the RR (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997b). The FIDF, which provided liquidity and capital support to illiquid or undercapitalized financial institutions, ultimately lost at least THB 244 billion, following the failure of 56 financial companies (Santiprabhob 2003).

On September 8, 1997, the BOT cut the RRR on domestic liabilities for both commercial banks and finance companies to 6% (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997; BOT 1997c; BOT 1997d). After the change:

- The BOT continued to require that commercial banks deposit 2% of this 6% with the BOT and to hold an additional 2.5% in unencumbered government securities and bonds (BOT 1997f).

- The BOT required finance companies to hold 0.5% of the 6% RRR with the BOT and 4.5% in unencumbered government assets (BOT 1997e).

As had been the case earlier, once the reserve requirement was satisfied, institutions could deposit the remaining reserves with the BOT or hold eligible deposits or assets (BOT 1997e; BOT 1997f).

At that time, the BOT left the RRR for nonresident deposits and foreign borrowing at 7%. In July 1998, the BOT brought the RRR for nonresident deposits and foreign borrowing into line with its domestic RR on bank deposits, dropping the RR to 6% (BOT 1999e).

Also in July 1998, the BOT expanded the list of assets that could fulfill the 6% RRR to include KTB and KTT debt, which was backed by the government (BOT 1998a; BOT 1998b).

In April 1999, while the domestic RRR remained at 6%, the BOT announced that commercial banks would only need to deposit 1% of the 6% with the BOT (BOT 1999a). Pursuant to Thai law, if banks did not meet their reserve requirement, the BOT could take action to ensure that the bank complied with the RR (Commercial Banking Act 1962, section 22). This included fining banks (Commercial Banking Act 1962, section 44). Commercial banks were still required to hold 2.5% of the 6% in unencumbered government assets (BOT 1999a).

Furthermore, that same month, the BOT released a revised list of institutions whose debt and bonds could satisfy the reserve requirement for commercial banks. This included 21 additional state enterprises, whose debt and bonds would be important to Thailand’s economy recovery, such as the export sector (BOT 1999c).

Reservable Liabilities

1

The BOT required banks and finance companies to hold reserves against specified liabilities. For commercial banks, the BOT used deposits and foreign short-term borrowing maturing within one year to calculate individual RRs; for finance companies, the BOT used deposits, foreign short-term borrowing, and all borrowing from the public (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997b; BOT 1999a; BOT 1999b).

Computation

1

Cash deposits at the BOT and unencumbered eligible liquid reserve assets were averaged over the end-of-day values of each day. Commercial banks had to meet the RRR over a two-week maintenance period (BOT 1997b; BOT 1997f). Finance companies had to meet the RRR over a weekly maintenance period (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997e).

The cash deposits with the BOT, along with the total of unencumbered eligible assets, were averaged daily at the end of each day (BOT 1997e; BOT 1997f).

The maintenance period for finance companies and commercial banks differed. Finance companies met the RRR over a weekly maintenance period (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997e). Commercial banks met the RRR over a fortnightly maintenance period (BOT 1997b; BOT 1997f).

Eligible Institutions

1

Commercial banks, including the BIBF, and other financial institutions operating in Thailand were required to hold liquid assets and comply with the RR. Commercial banks were subject to one set of liquidity rules, while finance companies and mortgage lenders were subject to another set of liquidity rules (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997b; Commercial Banking Act 1962, section 11; Finance Company Act 1979, section 28).

In 1996, leading into the AFC, the Thai system had 91 finance companies and 15 banks. By August 1997, the BOT had suspended the operations of 58 finance companies (Santiprabhob 2003).

Timing

1

On May 30, 1997, the BOT added the FIDF as an issuer whose debt could satisfy reserve requirements (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997b). That same week, outstanding debt from finance companies to the FIDF totaled at least THB 175.5 billion.FThis figure is complicated by the fact that borrowings by commercial banks are not disaggregated into FIDF and BOT borrowings, only BOT borrowings. Consequently, the figure may be THB 48.4 billion higher. The amount of FIDF bonds held by finance companies and commercial banks, the primary holders of debt, totaled THB 33 billion (BOT 2003b; BOT 2009). The BOT could advance the FIDF reserves, and it exacted mandatory member fees from Thai banks. However, the BOT appears not to have advanced the FIDF reserves, and mandatory fees were capped at just 0.1% of bank deposits (World Bank 1997).

The BOT lowered the RR on finance companies and commercial banks on September 7, 1997, when it announced new regulations governing 58 suspended institutions (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997). Months earlier, in July and August, Thailand had been forced to float the baht and sign an SBA with the IMF, as its economic situation worsened (Gov’t of Thailand 1997; Nabi and Shivakumar 2001). Nevertheless, Thai institutions continued to face a liquidity crunch into September (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997). These conditions also prompted Thai officials to enact other policies, such as a blanket deposit guarantee.

In July 1998, the BOT announced that KTB and KTT debt could be used to satisfy the RR. This decision corresponded to a program of consolidation of failed entities, which ultimately received government backing (BOT 1998a; BOT 1998b; Santiprabhob 2003).

Changes in Reserve Requirements

1

In September 1997, the BOT cut its domestic RRR for finance companies and commercial banks from 7% to 6% (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997; BOT 1997c; BOT 1997d). Thai officials expected the change to release THB 51.6 billion in liquidity (AFP 1997; Reuters 1997b). In July 1998, the BOT brought the RRR for nonresident deposits and foreign borrowing into line with its domestic RRR on bank deposits, dropping the RRR to 6% (BOT 1999e).

Deposit/Savings/Term Rates

For commercial banks, the RRR was 7%, and later 6%, on all deposits and on foreign short-term borrowing due within 365 days of the borrowing date and those repayable or recallable with 365 days. For finance companies and mortgage lenders, the RRR was 7%, later 6%, on deposits, foreign short-term borrowing due within 365, and all borrowing from the public (BOT 1997a, 4; BOT 1997b, 4; BOT 1999a; BOT 1999b).FThis definition was later changed to account for leap years, replacing “365 days” with “1 year,” so as to include “366 days” (BOT 1999d).

In July 1998, the BOT cut the RRR for nonresident baht deposits and foreign borrowing to 6%, bringing it in line with the domestic RRR (BOT 1999e).

Local/Foreign Currency Rates

The BOT exempted short-term borrowing from foreign countries made in foreign currency from the RRR (BOT 1997a; BOT 1997b).

Marginal Requirement

The sources consulted suggest that the BOT did not have such a requirement.

Changes in Interest/Remuneration

1

Reserves deposited with the BOT were not remunerated (BOT 2000). However, as noted in Key Design Decision No. 7, Assets Qualifying as Reserves, the BOT allowed companies to hold most of their required reserves in interest-bearing assets. In April 1999, the BOT adjusted the portion of reserves that it required commercial banks to hold on deposit with the BOT from 2% to 1% (BOT 1999a).

Other Restrictions

1

Sources consulted do not indicate that additional conditions accompanied changes to Thailand’s RR.

Impact on Monetary Policy Transmission

1

The BOT expected that changes to its RR would increase money supply and help Thai institutions facing a credit crunch (AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997). From the sources consulted, it seems that the BOT took no action to sterilize this increase.

Duration

1

The BOT’s announcements of RR adjustments did not include end dates. The RRR remained at 6% until 2016 (Tuncharoen 2015).

Key Program Documents

-

(Gov’t of Thailand 1997) Government of Thailand (Gov’t of Thailand). 1997. “Thailand Letter of Intent, August 14, 1997.”

Letter of intent for Thailand’s 34-month SBA with the IMF.

-

(BOT 2009) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 2009. “Assets and Liabilities of Finance Companies.” Dataset.

Data showing FIDF support to finance companies and purchases of FIDF bonds by finance companies.

-

(BOT Act [1985] 1942) Government of Thailand (BOT Act). [1985] 1942. Bank of Thailand Act. B.E. 2485.

BOT Act with amendments later than 1985 but before 2008.

-

(Commercial Banking Act 1962) Commercial Banking Act (Commercial Banking Act). 1962. Commercial Banking Act. B.E. 2505.

Law governing commercial banking in Thailand.

-

(Finance Company Act 1979) Government of Thailand (Finance Company Act). 1979. The Undertaking of Finance Business, Securities, and Credit Foncier Business Act. B.E. 2522.

Law governing finance companies and credit fonciers in Thailand.

-

(AFP 1997) AFP. 1997. “Thai Authorities Impose New Forex Controls, Bid to Boost Liquidity.” Agence France-Presse, September 8, 1997.

News article reporting estimates of liquidity released by changes to reserve requirements.

-

(Amorn 1997) Amorn, Vithoon. 1997. “FOCUS-Scepticism Greets Thai Liquidity Measures.” Reuters News, September 8, 1997.

News article highlighting the skeptical market response to Thailand’s market liquidity programs.

-

(AP-Dow Jones News Service 1997) AP-Dow Jones News Service. 1997. “Reserve Requirements Eased for Thai Commercial Banks.” The Wall Street Journal, September 9, 1997, sec. Front Section.

News article discussing the BOT’s motivation in lowering reserve requirements on domestic deposits from 7% to 6%.

-

(Bardacke 1997) Bardacke, Ted. 1997. “Bangkok Tries to Increase Liquidity.” Financial Times, September 9, 1997.

Article discussing Thailand’s lowering of reserve requirements from 7% to 6% of foreign borrowings.

-

(Reuters 1997a) Reuters. 1997a. “Thai Baht Weaker Late, Interbank Rate Eases.” Reuters News, September 8, 1997.

Article explaining the market effects of Thailand’s liquidity policies.

-

(Reuters 1997b) Reuters. 1997b. “Thai Central Bank Says New Moves to Steady Baht.” Reuters News, September 8, 1997.

News article discussing Thailand’s lowering of reserve requirements with estimates on liquidity released by these changes.

-

(BOT 1997a) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1997a. “Maintaining liquid assets of finance companies (5/30/1997).” Announcement 1627.

Circular announcing that the BOT would allow finance companies to satisfy their reserve requirements with FIDF liabilities.

-

(BOT 1997b) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1997b. “Prescribing commercial banks to maintain liquid assets (5/30/1997).” Announcement 1628.

Circular announcing that commercial banks could use FIDF liabilities to fulfill their reserve requirements.

-

(BOT 1997c) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1997c. “Bank of Thailand Announcement Regarding the Maintenance of Liquid Assets of Finance Companies (9/8/1997).” BOT Ngor. (Wor) 2841/2540.

Announcement that the BOT would cut the reserve requirement for financial companies to 6%.

-

(BOT 1997d) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1997d. “Bank of Thailand Notification Re: Requirement for Commercial Banks to Maintain Liquid Assets (9/8/1997).” BoT.N.P(Wor) 2840/2540. Circular.

Announcement that the reserve requirement for commercial banks was being lowered to 6%.

-

(BOT 1997e) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1997e. “Maintaining liquid assets of finance companies (9/8/1997).” Announcement.

Announcement that the BOT was cutting its reserve requirement for finance companies.

-

(BOT 1997f) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1997f. “Prescribing Commercial Banks to Maintain Liquid Assets (9/8/1997).” Announcement.

Announcement that the BOT was cutting the reserve requirement for commercial banks.

-

(BOT 1998a) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1998a. “Maintenance of Liquid Assets of Finance Companies (No. 2).” Announcement.

Announcement that the BOT would accept certain debt liabilities for finance companies’ reserve requirement.

-

(BOT 1998b) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1998b. “Prescribing Commercial Banks to Maintain Liquid Assets (No. 2).” Announcement.

BOT announcement that commercial banks could use certain liabilities to fulfill their reserve requirement.

-

(BOT 1998c) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1998c. “Prescribing Commercial Banks to Maintain Liquid Assets.” Announcement.

Circular that the BOT changed how it would define “short-term foreign borrowing” with relation to commercial banks.

-

(BOT 1999a) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1999a. “Re: The Notification of the Bank of Thailand Re: Prescription on Maintenance of Liquid Assets by Commercial Banks.” BOT.X(C).

Notification that the BOT would lower the portion of the RR that it would require commercial banks to deposit with the BOT.

-

(BOT 1999b) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1999b. “Re: The Notification of the Bank of Thailand Re: Prescription on Maintenance of Liquid Assets by Finance Companies.” BOT.X(C) 1231/2542.

Notification that the BOT would change how it approached short-term foreign borrowing of finance companies.

-

(BOT 1999c) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1999c. “Re: List of Additional Institutions Whose Debentures or Bonds Are Permitted to Be Maintained by Commercial Banks as Liquid Assets.” ThorPorThor.Ngor. (Wor) 1345/2542. Circular.

Announcement that commercial banks could use debt and bonds from additional institutions to satisfy BOT reserve requirement.

-

(BOT 1999d) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1999d. “Changing the Definition of Short Term Foreign Borrowings Subject to Liquidity Reserve Requirement.” 3862/2542.

Circular that changed how the BOT defined “short-term foreign borrowing” to include leap years.

-

(BOT 1997g) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1997g. “Supervision Report 1996/7.”

Report discussing the BOT’s actions in 1996 and 1997 with respect to its reserve requirements.

-

(BOT 1998d) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1998d. “International Reserves.” EC_XT_030. Bangkok: Bank of Thailand.

Data showing the diminution of BOT reserves during its currency crisis.

-

(BOT 1999e) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 1999e. “Annual Economic Report 1998.” Bank of Thailand.

Annual report describing the terms of government capital offered through credit support facilities and the legislation relevant to participation in those facilities.

-

(BOT 2000) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 2000. “Annual Economic Report 1999.” Bank of Thailand.

Annual report containing information on the BOT’s acceptance of hybrid securities as part of matchable capital under the credit support facilities.

-

(BOT 2003a) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 2003a. “Loan of Finance and Finance & Securities Companies Classified by Purpose (Outstanding).” XLS_MB_030. Bangkok: Bank of Thailand.

Data showing the composition of finance company portfolios before and during the crisis.

-

(BOT 2003b) Bank of Thailand (BOT). 2003b. “Operation of Commercial Banks.” XLS_MB_006. Bangkok: Bank of Thailand.

Data showing the sources and uses of commercial banks funds during the crisis.

-

(Haksar and Giorgianni 2000) Haksar, Vikram, and Lorenzo Giorgianni. 2000. “Financial Sector Restructuring.” In Thailand: Selected Issues, 27–44. IMF Staff Country Report No. 00/21, February 2000. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Staff report describing Thailand’s economic crisis and measures taken by the government.

-

(Santiprabhob 2003) Santiprabhob, Veerathai. 2003. Lessons Learned from Thailand’s Experience with Financial-Sector Restructuring. Bangkok, Thailand: Thailand Development Research Institute.

Study commissioned by one of Thailand’s think tanks analyzing the government’s response to the crisis.

-

(World Bank 1997) World Bank. 1997. “Proposed Loan in the Amount of US$350 Million to the Kingdom of Thailand for Finance Companies Restructuring.” Report and recommendation P-7211-TH. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Proposal describing funding, pricing, exit strategy, and size of FIDF crisis support.

-

(World Bank 1999) World Bank. 1999. “World Bank Report No. P 7271-TH.” Report and recommendation P-7271-TH. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Report discussing the Thai financial crisis and a potential loan to Thailand.

-

(Dasri 1990) Dasri, Tumnong. 1990. The Reserve Requirement as a Monetary Instrument in the SEACEN Countries. Kuala Lumpur: South East Asian Central Banks Research and Training Centre.

Book discussing the use of the RR in SEACEN countries.

-

(Kulam 2020) Kulam, Adam. 2020. “Thailand Capital Support Facilities 1998.” Journal of Financial Crises 3, no. 3: 664–704.

Case study examining Thailand’s capital injection program during the AFC.

-

(Nabi and Shivakumar 2001) Nabi, Ijaz, and Jayasankar Shivakumar. 2001. “Back from the Brink: Thailand’s Response to the 1997 Economic Crisis.” Directions in Development. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

World Bank study describing the causes and response of Thailand to the currency, financial, and economic crises.

-

(Sharma 2013) Sharma, Shalendra D. 2013. “Thailand: Crisis, Reform and Recovery.” In The Asian Financial Crisis: Crisis, Reform and Recovery. Manchester University Press.

Book chapter discussing Thailand’s response to the AFC.

-

(Sutham 1997) Sutham, Apisith John. 1997. “The Asian Financial Crisis and the Deregulation and Liberalization of Thailand’s Financial Services Sector: Barbarians at the Gate.” Fordham International Law Journal 21, no. 5: 53.

Article examining some of Thailand’s policy responses to the AFC.

-

(Tuncharoen 2015) Tuncharoen, Teerawat. 2015. “Re: The Requirements for Commercial Banks on the Maintenance of Reserve Balances at the Bank of Thailand (Reserve Requirement)” No.: SorKorNgor. 56/2558, September: 6.

Unofficial translation of the BOT announcement of reserve balance requirements for commercial banks.

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Reserve Requirements

Countries and Regions:

- Thailand

Crises:

- Asian Financial Crisis 1997