Market Support Programs

Thailand: Bond Stabilization Fund

Purpose

To backstop companies that could not “fully rollover maturing corporate bonds” (BOT, MOF, and SEC 2020)

Key Terms

-

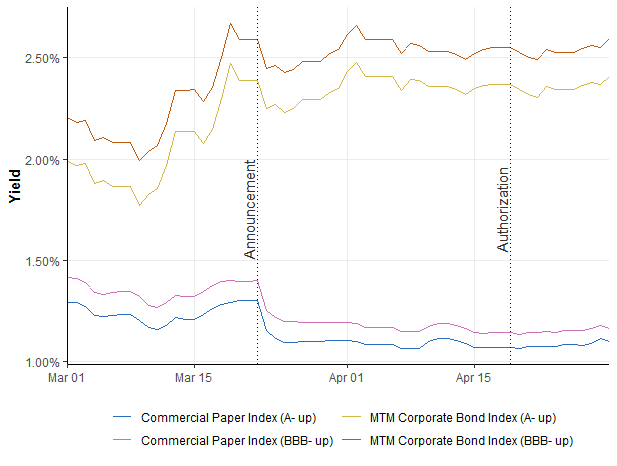

Launch DatesAnnounced: March 22, 2020 Authorized: April 19, 2020

-

Operational DateSPV established: April 19, 2020 First accepted applications: April 29, 2020

-

End DateLast application to be accepted by December 31, 2022

-

Legal AuthorityEmergency Decree B.E. 2563

-

Source(s) of FundingOriginally public-sector enterprises, insurance providers, and the Thai Bankers Association; ultimately BOT

-

AdministratorKrung Thai Asset Management

-

Overall SizeTHB 400 billion

-

Eligible Collateral (or Purchased Assets)Newly issued commercial paper

-

Peak UtilizationNot used

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

Part of a Package

Governance

Administration

Communication

Disclosure

SPV Involvement

Program Size

Source(s) of Funding

Eligible Institutions

Auction or Standing Facility

Loan or Purchase

Eligible Collateral or Assets

Loan Amounts (or Purchase Price)

Haircuts

Interest Rate

Fees

Term

Other Conditions

Regulatory Relief

International Cooperation

Duration

Key Program Documents

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Market Support Programs

Countries and Regions:

- Thailand

Crises:

- COVID-19