Market Support Programs

Public-Private Investment Program: The Legacy Securities Program (US)

Purpose

To create demand and provide liquidity for legacy mortgage securities

Key Terms

-

Announcement DateMarch 23, 2009

-

Operational DateQ4 2009

-

Expiration DateQ4 2013

-

Legal AuthorityEmergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008; Troubled Asset Relief Program; Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act

-

Program MechanicsNine public-private investment funds bought mortgage securities in the open market using a combination of private equity, Treasury equity, and Treasury debt

-

Amount Invested$24.9 billion ($18.6 of which was government funding)

-

Government SponsorsU.S. Treasury; Federal Reserve Board

On March 23, 2009, the U.S. Treasury, in conjunction with the Federal Reserve (Fed) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), announced the Public-Private Investment Program (PPIP). PPIP consisted of two complementary programs designed to foster liquidity in the market for certain mortgage-related assets: The Legacy Loans Program and the Legacy Securities Program. This case study discusses the design and implementation of the Legacy Securities Program. Under this program, the Treasury formed an investment partnership with nine private sector firms it selected at the conclusion of a months-long application process. Using a combination of private equity and debt and equity from the Treasury, nine public-private investment funds (PPIFs) invested $24.9 billion in non-agency residential and commercial mortgage-backed securities (MBS), netting the government a positive return of $3.9 billion on its investment. While the program received mixed reviews from scholars, the private sector, and former government officials, it is seen as having contributed somewhat to the recovery of the secondary mortgage market.

By the fall of 2008, troubled mortgage-related assets had become inextricably linked to the onset of the Global Financial Crisis. Marked down to only a fraction of what they once were worth, these assets weighed heavily on financial institutions in possession of them, consuming their capital, raising concerns as to their solvency, and inhibiting their ability to make new loans.

On March 23, 2009, the U.S. Treasury, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and Federal Reserve announced the Public-Private Investment Program (PPIP), consisting of two complementary programs designed to provide up to $500 billion in liquidity for these assets: The Legacy Loans Program and the Legacy Securities Program. This case study discusses the design and implementation of the Legacy Securities Program.

Under this program, the Treasury created investment partnerships with nine private sector firms it selected at the conclusion of a months-long application process. Using a combination of private equity and debt and equity from the Treasury, the nine public-private investment funds (PPIFs) invested $24.9 billion in non-agency residential and commercial mortgage-backed securities, netting the government a positive return of $3.9 billion on its investment.

The market initially responded positively to the announcement of PPIP; the S&P 500 and Dow Jones Industrial Average both had gains of 7% on that day. However, the market later cooled to the idea of the program after it took months to develop and appeared increasingly unlikely to realize its full potential.

The exact impact of the Legacy Securities Program is difficult to pinpoint given that the program was just one small part of the government’s broader crisis-fighting strategy. Despite the existence of no scholarly literature attempting to isolate the effects of the program, the Treasury has credited the program with helping to achieve its stated goals.

Key Design Decisions

Purpose of MLP

1

In early 2009, huge markdowns on mortgage-related assets continued to afflict the banks in possession of them, consuming their capital and inhibiting their ability to make new loans (PPIP White Paper 2009). That March, in recognition of the risks associated with these assets, the Treasury established the Public-Private Investment Program (PPIP) with two primary goals in mind. The obvious aim was to create new demand for troubled mortgage-related assets, thus enabling financial institutions to sell them. At the same time, the Treasury wanted a considerable portion of new demand to be from private investors. In order to achieve this, it formed investment partnerships with them.

While the government could have purchased these assets on its own, it concluded that incorporating the private sector into its approach had three clear advantages: It would (1) “[leverage] the impact of each taxpayer dollar,” enabling for the purchase of more assets using less TARP funding; (2) reduce government exposure to risk, as the private sector would help to shoulder any losses on the investments; and (3) “provide a mechanism for valuing the assets,” helping the government to avoid paying the wrong price for them, which would have further distorted the dysfunctional market it sought to fix (PPIP Fact Sheet 2009; Elliott 2009; Financial Crisis Manual).

Legal Authority

1

Created by Congress in October 2008 with the enactment of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (EESA), TARP enabled the Treasury “to purchase and insure certain types of troubled assets for the purposes of providing stability to and preventing disruption in the economy and financial system” (Public Law 110—343). The law defined troubled assets as:

(A) residential or commercial mortgages and any securities, obligations, or other instruments that are based on or related to such mortgages, that in each case was originated or issued on or before March 14, 2008, the purchase of which the Secretary determines promotes financial market stability; and (B) any other financial instrument that the Secretary, after consultation with the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, determines the purchase of which is necessary to promote financial market stability, but only upon transmittal of such determination, in writing, to the appropriate committees of Congress (Public Law 110—343).

Legacy loans and securities that were eligible for purchase through PPIP largely conformed to the description in definition (A). However, given the existence of definition (B), the Treasury Secretary also had the authority to decide if other assets needed to be purchased and what characteristics to apply to them.FThe definition of legacy securities under PPIP, for instance, ran afoul of definition (A) in EESA in that legacy securities only had to be “issued before 2009”—not March 14, 2008.

Program Size

1

At the inception of PPIP, the Treasury committed up to $100 billion in TARP funding for its implementation. Utilizing a combination of TARP funding, private equity, and outside financing, the program was supposed to provide for the purchase at least $500 billion in legacy assets. Later on, however, it became apparent that the program would not be able to achieve this scope. By July 2009, the Treasury had reduced its commitment for the Legacy Securities Program to just $30 billion, while the status of the Legacy Loans Program remained “in doubt” (SIGTARP Q3 2009).

Administration

1

The Treasury sponsored the creation of the Legacy Securities Program and initially committed up to $100 billion in TARP funding for the implementation of it (although this amount soon was reduced to $30 billion). The Treasury’s primary responsibilities included: (1) conducting an application process pursuant to which it selected firms to become fund managers, (2) meeting the PPIFs’ funding needs (matching private capital raised by them and setting up credit facilities for those accepting Treasury debt), and (3) maintaining oversight of the PPIFs as they purchased assets with public funding but largely at their own discretion.

Throughout the program, the Treasury interacted with and received help from a number of government agencies and private firms. During the application period, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, a law firm, assisted with drafting application materials and setting evaluation standards; individuals from other government agencies (including the Export-Import Bank and Overseas Private Investment Corporation) served on the Evaluation Committee, helping to choose responsible fund managers; and Ennis Knupp & Associates, a consulting firm, advised the Evaluation Committee as it reviewed applications.

In addition, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PWC) and the Bank of New York Mellon (BNY Mellon) helped the Treasury to set up an extensive regulatory and oversight system. PWC supervised PPIFs with respect to rules concerning fraud and abuse of funds, while BNY Mellon served in the role of “administrative agent, custodian, and valuation agent” for the PPIFs (SIGTARP Q4 2009 report).

Program Duration

1

This timeline allowed for PPIFs to make long-term investments rather than short-term and speculative deals. The Treasury’s stated goal of these investments was to: “generate attractive returns for taxpayers and private investors through long-term opportunistic investments in Eligible Assets . . . by following predominantly a buy and hold strategy” (PPIP quarterly reports).

Private Sector Support

1

Because the private market was hesitant to invest in legacy securities, the government needed to provide an incentive for it to do so as part of the Legacy Securities Program. The program aimed to do this “by providing government equity co-investment and attractive public financing” to these investors (PPIP White Paper 2009).

Public funding for asset purchases included matching Treasury equity as well as debt financing from the Treasury and/or outside financing sources. As described above, half turn financing offered PPIFs access to Treasury debt worth 50% of their aggregate capital—while giving them the opportunity to obtain debt elsewhere—and full turn offered them access to Treasury debt worth 100% of their total capital—while prohibiting them from accepting other funding (Legacy Loans Program Summary of Terms 2009).

Loans from the Treasury were nonrecourse, which served to limit potential losses for private stakeholders to only the equity they contributed. In addition, the loans were extended at interest rates of 1-month Libor + 100 basis points (full turn) or 1-month Libor + 200 basis points (half turn).FFor PPIFs choosing half turn financing, this rate was subject to increases depending on the leverage they assumed from elsewhere (Financial Crisis Manual). Altogether, the terms of the funding were intended to be “attractive” to private investors, and the rates were considered by some to be “well below” what it would have cost to finance the purchase of these assets elsewhere (PPIP Fact Sheet 2009; Dash 2010).

At the same time, the provision of cheap public financing was also supposed to increase investor tolerance for paying higher prices for them (Financial Crisis Manual). In this way, the program would encourage holders of these assets to now choose to sell them (Financial Crisis Manual).

Loss- and Profit-Sharing Arrangements

2

Realized profits and losses were divided among investors in line with their shares in each PPIF (notwithstanding the Treasury’s privilege to an additional portion of profits—should there be any—per the warrants it received) (Financial Crisis Manual).

A key facet of Treasury’s arrangement with fund managers was that they were required to invest at least $20 million of their firm’s funds in their own PPIF. This was done to ensure that they had “skin in the game”—i.e., a vested interest in the performance of their own fund (SIGTARP Q3 2009). As noted above, fund managers—like other investors—were prepared to forfeit this equity should their investment decisions yield results that wiped it out (PPIP White Paper 2009).

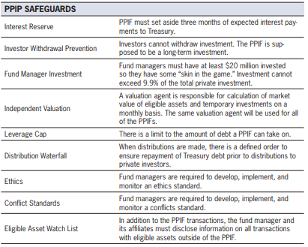

In addition to this requirement, as shown in Figure 4, fund managers were forced to abide by a number rules that were intended to shield the Treasury’s investment, including restrictions on leverage, the use of a third party to value PPIF portfolios, and detailed conflict-of-interest directives (SIGTARP Report, Q3 2009).

Figure 4: Legacy Securities Program Investment Protections

Source: SIGTARP Report, Q3 2009

Finally, as the program was developed throughout 2009, the Treasury responded to a number of concerns about potential misuse of public funding. It instituted rules barring devious behavior such as “asset crossing,” “asset flipping,” and “round tripping”—all of which essentially involved a fund manager conspiring with other firms to earn side profits on transactions—and reducing opportunities for fund managers to favor the interests of their clients and subsidiaries over those of the Treasury’s (SIGTARP Report, Q3 2009). (For more information on concerns raised and rules implemented in response to concerns raised by SIGTARP, see Table 2.25 on pages 91 and 92 of the Special Inspector General for TARP’s 3rd Quarter 2009 Report to Congress.)

Eligible Institutions

2

Direct participation in the program was limited to private sector firms chosen to serve as PPIF fund managers. The Treasury initially anticipated choosing five fund managers, although it ultimately chose nine after receiving 141 applications for the position. Even if a private sector firm were not chosen to be a fund manager, it could participate in the program in the form of a regular investor and purchase an equity stake in individual PPIFs. According to Davis Polk & Wardwell, this option was available even to foreign firms (Financial Crisis Manual).

The Treasury appointed nine fund managers at the conclusion of a months-long application process. It established an Evaluation Committee and charged it with judging applicants according to the evaluation standards listed below:

- “Demonstrated capacity to raise at least $500 million in private sector capital.”

- “Demonstrated experience investing in Eligible Assets, including through performance track records.”

- “A minimum of $10 billion (market value) of Eligible Assets under management.”

- “Demonstrated operational capacity to manage the Funds in a manner consistent with Treasury’s stated Investment ObjectiveFThe Treasury’s stated investment objective was to “generate attractive returns . . . through long-term opportunistic investments in Eligible Assets” (Legacy Securities Summary of Terms). while also protecting taxpayers.”

- “Headquartered in the United States” (Fund Manager Application).

Although the Treasury later clarified that these criteria were intended to be flexible—i.e., that failing to meet one or more would not necessarily rule out an applicant—the government wanted to ensure that fund managers were capable of raising capital from the private sector and making sound investments. Moreover, analysts at the Center for American Progress deemed these criteria to be important because the government needed (1) to be able to trust fund managers with public money, (2) to ensure that PPIF activity acted to support market functioning, and (3) to be able to count on fund managers to work in support of related efforts, such as foreclosure prevention programs (Ettlinger et al. 2009).

EESA gave a particularly broad description of financial institutions, defining them as “any institution, including, but not limited to, any bank, savings association, credit union, security broker or dealer, or insurance company, established and regulated under the laws of the United States or any State, territory, or possession of the United States, the District of Columbia, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, American Samoa, or the United States Virgin Islands, and having significant operations in the United States, but excluding any central bank of, or institution owned by, a foreign government” (Public Law 110—363).

Eligible Collateral or Assets

1

As opposed to other government programs, which sought to promote new issuance of asset-backed securities, the Legacy Securities Program was designed to “restart the [secondary] market for legacy securities” that had already been issued and were held by banks and other financial institutions. According to the Treasury, the prevalence of these assets impeded the financial system’s ability to make new loans and jeopardized the country’s recovery from recession.

As such, the Treasury defined eligible assets so as to target these securities. Eligible assets included non-agency (not issued by a government agency or government-sponsored enterprise) RMBS and CMBS that were (1) “issued prior to 2009,” (2) “originally rated AAA or an equivalent rating by two or more national recognized statistical rating organizations without ratings enhancement,” (3) “secured by the actual mortgage loans, leases or other assets and not [by] other securities,” at least 90% of which were located in the United States, and (4) owned by a U.S. financial institution, as defined by the EESA (Legacy Securities Summary of Terms). Because securities had to be secured by actual loans or leases, AAA-rated CDOs were ineligible for the program.

Relief from Other

1

In announcing such a decision, the Treasury reasoned that it developed the PPIP to leverage private sector resources and expertise for purchasing legacy assets and the TALF with the Fed for funding legacy assets. Therefore, asset managers or private investors participating in PPIP were exempt from executive compensation restrictions if the PPIFs are structured such that the asset managers themselves and their employees are not employees of or controlling investors in the PPIFs, and other investors are purely passive (FAQ April 6, 2009).

Related Programs

1

In February 2009, the Obama Treasury announced its Financial Stability Plan. Even though a wide array of financial stability efforts were already underway, the Obama Treasury saw the need for a second wave of crisis-fighting programs—ones specifically designed to “attack the credit crisis on all fronts” (Financial Stability Plan 2009). The plan involved the participation of several government agencies and—in addition to PPIP—included proposals that ultimately became the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP), Capital Assistance Program (CAP), expansion of TALF, Small Business Administration Section 7(a) Securities Purchase Program, and foreclosure prevention programs including the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP) and Home Affordable Refinance Program (HARP).

The exact impact of the Legacy Securities Program is difficult to pinpoint given that the program was a relatively small part of the government’s broader crisis-fighting strategy; as of this writing, no scholarly attempt has been made to determine the effects of the program.

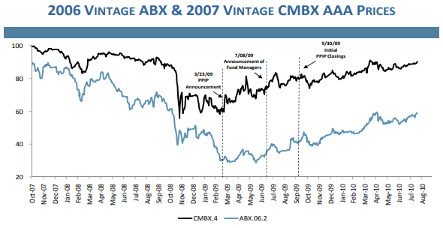

Despite this, the Treasury is convinced that the program contributed positively to the government’s broader efforts and played some role in diminishing the crisis. Figure 5 below shows that certain benchmarks for legacy securities prices indeed rose steadily throughout the implementation of the Legacy Securities Program. Even if its contributions have not yet been quantified, the Treasury credits the program with helping to achieve the goal of “restarting the market for legacy securities, thereby allowing banks to begin reducing their holdings in such assets at more normalized prices” (TARP Two Year Retrospective 2010).

Figure 5: Benchmark Legacy Security Prices During the Global Financial Crisis

Source: TARP Two Year Retrospective 2010

Government officials and critics in the media and academic community disagree on why the Legacy Securities Program ultimately failed to realize its full potential, having utilized only $18.6 billion of the envisioned $75 billion to $100 billion in TARP funding. Former US Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner cites the rapid improvement in financial markets in the time between PPIP’s announcement and its readiness to be implemented (Geithner 2015). By mid-July, for example, when the PPIFs began to raise private capital, several of the largest US banks had already succeeded at raising their own capital, and credit conditions had eased considerably.FFrom March 23, 2009, to July 8, 2009, the 3-month Libor-OIS spread shrank from 99.02 basis points (bps) to just 32.5 bps. Looser credit conditions also were beginning to extend to the broader economy, with banks reporting significantly looser lending standards in the Federal Reserve’s quarterly survey on bank lending.

Others have suggested, however, that programmatic design problems doomed the program from the very beginning. Economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, for example, thought that the design of the program was inherently flawed; while the program offered a clear advantage to private investors, he believed that banks selling these assets would see a minimal increase in the price being offered for them. In his opinion, this misalignment of incentives for buyers and sellers would produce a stalemate between them, rendering the program largely ineffective (Krugman 2009a; Krugman 2009b).

Despite the Legacy Securities Program’s having been implemented on a smaller scale, Fannie Chen of Columbia Law School believes that the program is a positive example of the potential for public-private partnerships; a survey of program participants conducted by Chen revealed that Treasury was perceived to have managed the partnerships with transparency and effectiveness (Chen 2013).

- Chen, Fannie. 2013. “Structuring Public-Private Partnerships: Implications from…

- Dash, Eric. 2010. “A Big Surprise: Troubled Assets Garner Rewards.” New York Ti…

- Davis Polk & Wardwell. 2009. A Guide to the Laws, Regulations and Contracts of …

- Davis Polk & Wardwell. 2009. “The Public-Private Investment Program.” March 25,…

- Elliott, Douglas J. 2013. “The Public-Private Investment Program: An Assessment…

- Ettlinger, M., A. Jakabovics, and D. Min. 2009. “Recommendations for the Public…

- Enrich, David. 2009. “Wary Banks Hobble Toxic-Asset Plan.” Wall Street Journal,…

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2009. “Fact Sheet: Public-Private Investment P…

- FDIC. 2009. “FDIC Statement on the Status of the Legacy Loans Program.”

- Geithner, Timothy. 2009. “My Plan for Bad Bank Assets.” Wall Street Journal, Ma…

- Geithner, Timothy F. 2014. Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises. New Yo…

- Laise, Eleanor. 2010. “TCW Pulling Out of PPIP.” Wall Street Journal, January 6…

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2009. “Legacy Loans Program Summary of Terms.”

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2009 “Legacy Securities Public-Private Investm…

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2009. “Legacy Securities Public-Private Invest…

- Poirier, John. 2009. “FDIC Tests Toxic Assets Sale Program.” Reuters, July 31, …

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2012. “Public-Private Investment Program: Prog…

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2009. “Public-Private Investment Program: Whit…

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2013. “Legacy Securities Public-Private Invest…

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2009a. “Treasury Department Releases Details o…

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. 2009b. “Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner Ou…

- U.S. Department of the Treasury Office of Financial Stability, 2010. “Troubled …

Key Program Documents

-

Fact Sheet: Public-Private Investment Program

Fact sheet providing detailed information on the framework for PPIP released as part of the Treasury Department’s introduction of the program

-

Legacy Loans Program Summary of Terms

Outline of FDIC-dictated terms of the Legacy Loans Program

-

Legacy Securities Public-Private Investment Program Additional Frequently Asked Questions

Treasury document providing frequently asked questions and corresponding responses concerning key features of the Legacy Securities PPIP

-

Public-Private Investment Program Legacy Loans Program Frequently Asked Questions

Treasury document providing frequently asked questions and corresponding responses concerning key features of the Legacy Loans PPIP

-

Application for Private Asset Managers

Application for prequalification as a private asset manager for a Public-Private Investment Fund under the Legacy Securities Program

-

Guidelines for the Legacy Securities Public-Private Investment Program

Supporting document outlining program goals, application criteria, and terms and conditions tied to Treasury financing

-

Letter of Intent and Terms Sheet

Agreement outlining the specific terms and conditions of the limited partnership between the Treasury and private sector fund managers

-

Summary of Conflict of Interest Rules and Ethical Guidelines

Treasury document summarizing the conflict of interest rules and guidelines developed to ensure private sector firms aligned themselves with the public interest

-

FDIC Statement on the Status of the Legacy Loans Program (06/03/2009)

FDIC formal announcement that a planned pilot sale of loans would be postponed

-

Public-Private Investment Program Press Releases

Treasury’s comprehensive list of press releases pertaining to the announcement, design, status, and implementation of the program

-

Secretary Timothy F. Geithner’s Written Testimony Before the Congressional Oversight Panel (12/16/2010)

Secretary Geithner’s overview of the financial rescue efforts undertaken by the Treasury up to that time, including PPIP

-

Treasury Department Announces Initial Closings of Legacy Securities Public-Private Investment Funds (09/30/2009)

Treasury press release announcing the first two firms to have completed initial raises in capital

-

Treasury Department Announces Initial Quarterly Report for the Legacy Securities Public-Private Investment Program (1/29/2010)

Treasury press release linking to first quarterly report on the funds’ progress

-

Treasury Department Releases Details on Public Private Partnership Investment Program (03/23/2009)

Treasury press release detailing the design of the Public Private Investment Program

-

Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner Outlines Comprehensive Financial Stability Plan (02/10/2009)

Treasury press release announcing the new administration’s Financial Stability Plan

-

A Big Surprise: Troubled Assets Garner Rewards (New York Times – 08/26/2010)

Article discussing the profitability of PPIFs up to that date

-

Treasury Picks Nine Managers for P.P.I.P (New York Times – 07/08/2009)

Article discussing the announcement of funds managers and programmatic changes moving forward

-

U.S. Expands Plan to Buy Banks’ Troubled Assets (New York Times – 03/23/2009)

Article pertaining to the announcement of details for PPIP

-

Wary Banks Hobble Toxic Assets Plan (Wall Street Journal – 06/29/2009)

Article discussing difficulties with implementation of the program before the Treasury eventually moved on with only the Legacy Securities Program

-

A Binomial Model of Geithner’s Toxic Asset Plan (Wilson 2010)

Paper solving for the clearing price of toxic assets under PPIP according to various financing terms

-

Slicing the Toxic Pizza – An Analysis of FDIC’s Legacy Loan Program for Receivership Assets (Wilson 2010)

Paper discussing the structure of the Legacy Loans Program and maximizing the value of toxic asset portfolios put up for auction

-

Structuring Public-Private Partnerships: Implications from the Public-Private Investment Program for Legacy Securities (Chen 2013)

Paper drawing upon interviews with private sector PPIP participants to better understand successes and failures of PPIP and how to apply them to future public-private partnerships

-

Subsidizing Price Discovery (Camargo et. al 2012)

Paper illuminating the inefficiencies plaguing the market for mortgage-related assets and how PPIP targeted them, concluding with how to determine the “optimal leverage ratio”

-

Public-Private Investment Program Quarterly Reports

Treasury’s 16 quarterly reports documenting details on the funds, their investments, and returns (last report issued September 2013)

-

Selecting Fund Managers for the Legacy Securities Public-Private Investment Program (Office of the Special Inspector General for the Troubled Asset Relief Program 10/07/2010)

Inspector General’s report on the application and selection process used by Treasury for fund managers

-

Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP): Implementation and Status (Congressional Research Service 2011)

Paper providing overview of TARP programs and evaluation of them up to 2011

-

Troubled Asset Relief Program: Status of Programs and Implementation of GAO Recommendations (United States Government Accountability Office 2011)

GAO evaluation of and recommendations for TARP programs issued prior to January 2011

-

Troubled Asset Relief Program: Two Year Retrospective (United States Department of the Treasury Office of Financial Stability 2010)

Office of Financial Stability overview of the recovery programs employed as part of TARP and evaluation of those programs

|

GDP per capita (SAAR, Nominal GDP in LCU converted to USD) |

$47,976 in 2007 $48,383 in 2008 Source: Bloomberg |

|

Sovereign credit rating (5-year senior debt)

|

As of Q4, 2007: Fitch: AAA Moody’s: Aaa S&P: AAA

As of Q4, 2008: Fitch: AAA Moody’s: Aaa S&P: AAA Source: Bloomberg |

|

Size of banking system

|

$9,231.7 billion in total assets in 2007 $9,938.3 billion in total assets in 2008 Source: Bloomberg |

|

Size of banking system as a percentage of GDP

|

62.9% in 2007 68.3% in 2008 Source: Bloomberg |

|

Size of banking system as a percentage of financial system

|

Banking system assets equal to 29.0% of financial system in 2007 Banking system assets equal to 30.5% of financial system in 2008 Source: World Bank Global Financial Development Database |

|

5-bank concentration of banking system

|

43.9% of total banking assets in 2007 44.9% of total banking assets in 2008 Source: World Bank Global Financial Development Database |

|

Foreign involvement in banking system |

22% of total banking assets in 2007 18% of total banking assets in 2008 Source: World Bank Global Financial Development Database |

|

Government ownership of banking system

|

0% of banks owned by the state in 2008 Source: World Bank, Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey |

|

Existence of deposit insurance |

100% insurance on deposits up to $100,000 for 2007 100% insurance on deposits up to $250,000 for 2008 Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Market Support Programs

Countries and Regions:

- United States

Crises:

- Global Financial Crisis