Resolution and Restructuring in Europe: Pre- and Post-BRRD

Portugal: Banco Espírito Santo Restructuring, 2014

Purpose

“To safeguard the financial soundness of Banco Espírito Santo, S.A. and the interest of its depositors, as well as to maintain the stability of the Portuguese financial system.” (BOP 2014a)

Key Terms

-

Size and Nature of InstitutionSecond-largest private bank in Portugal with assets of EUR 80 billion (approx. 35% of GDP)

-

Source of FailureElevated levels of NPLs; Improper lending to BES’s parent, the ES group

-

Start DateAugust 3, 2014

-

End DateGovernment of Portugal (GOP) held a 25% stake in Novo Banco as of November 2023

-

Approach to Resolution and RestructuringNovo Banco received two capital injections: (1) EUR 4.9 billion in 2014 (EUR 3.9 billion from the state, and EUR 1.0 billion from private banks); (2) EUR 3.4 billion over 2018–2021 under the Contingent Capital Agreement (from the state). BES had earlier raised EUR 1.04 billion from a public offering in June 2014; most assets transferred to a bridge bank, Novo Banco, which was sold to private investors in 2017; the bad bank comprised some NPLs and all equity, subordinated liabilities, and ES-linked liabilities, which was wound down in July 2016

-

OutcomesNovo Banco received EUR 8.3 billion of capital injections over 2014–21, with the Portuguese state providing EUR 7.3 billion; equity, subordinated debt, and other liabilities remained with the bad bank; the Bank of Portugal (BOP) imposed losses on EUR 2.2 billion of senior debt holders in 2015; Lone Star injected EUR 1.0 billion into Novo Banco to purchase 75%; GOP’s 25% stake in Novo Banco had a book value of EUR 1.1 billion as of 2023

-

Notable FeaturesThe government transferred nearly all assets to the bridge bank; One year after the creation of Novo Banco, the BOP transferred EUR 2.2 billion of bonds from Novo Banco; this led to uncertainty for the senior unsecured debt of European banks; in 2017, the Resolution Fund did not receive anything for selling 75% of Novo Banco to Lone Star; the Fund also had to commit to an additional EUR 3.9 billion of capital, adding pressure on the overall banking system

Banco Espírito Santo (BES) was the second-largest private bank in Portugal in 2014, with assets of EUR 80 billion (USD 81 billion). A capital increase of EUR 1.1 billion to the BES was concluded on market terms in June 2014. In July 2014, BES breached minimum capital requirements and reported a EUR 3.6 billion loss owing to improper loans made to the nonfinancial arm of the Espírito Santo (ES) group. The Bank of Portugal (BOP) adopted a resolution measure for BES on August 3, 2014, to safeguard financial stability by protecting all depositors and ensuring continuation of operating activities of the bank. The Portuguese Resolution Fund provided equity capital of EUR 4.9 billion to a bridge bank, Novo Banco, with 100% public ownership and the expectation of sale to private investors in two years. Nearly all assets of the bank, as well as depositors and senior liabilities, were moved to Novo Banco. The legacy bank retained a small portfolio of assets, mostly linked to the ES group, as well as equity, subordinated debt, and ES-linked liabilities. It began its winddown with the setup of Novo Banco and would have its banking license revoked after the sale of the bridge bank. In 2015 and 2016, both Novo Banco and the legacy bad bank continued to report capital losses due to impairment of loans, as the BOP missed its own deadline for the sale of the bridge bank. In 2017, the BOP and the Resolution Fund sold a 75% stake in Novo Banco to Lone Star, a US-based private equity fund, in return for a commitment to inject EUR 1.0 billion of new capital into Novo Banco. The Resolution Fund agreed to provide up to EUR 3.9 billion of additional capital to Novo Banco from the Resolution Fund if the bank’s Tier 1 capital ratio dropped below 12%; as of November 2023, the Resolution Fund had injected EUR 3.4 billion in capital into Novo Banco. The Resolution Fund was backed by public and private loans to be recouped via contributions from the banking sector over a prolonged time span. In February 2023, the European Commission (EC) officially declared the end of the restructuring process of Novo Banco, which meant the end of the EC’s monitoring of the bank. The Government of Portugal and the Resolution Fund provided EUR 7.3 billion of capital injections to Novo Banco between 2014 and 2021 and continues to hold a joint 25% stake in Novo Banco with a book value of EUR 1.1 billion (GOP holds 12% and Resolution Fund holds 13%).

This module is about the resolution and restructuring measures provided to Banco Espírito Santo (BES) starting in 2014. There is another module of this case in the ad hoc capital injection series, which describes the capital injection that the government also initiated in August 2014 (see Gupta, forthcoming).

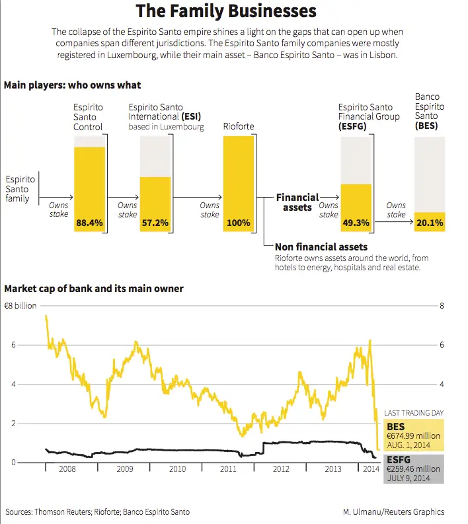

Founded in 1869, Espírito Santo International (ES) was one of Portugal’s largest conglomerates that is privately-owned with various business holdings including real estate, hotels, financials, and hospitals. The ES group owned 49% of a publicly listed financial arm Espírito Santo Financial Group (ESFG), which owned 27% of BES in May 2014 (Kowsmann 2014a). Prior to the restructuring announcement, ESFG’s ownership of the bank had dropped to 20%, while the other 36% of major shareholders were various private banks, investors, and asset management companies (see Figure 1) (Benedetti-Valentini 2014; BES 2014a; EC 2014b). Crédit AgricoleFCrédit Agricole helped the Espírito Santo family regain control of the bank and insurer from the Portuguese Government in 1989 (Benedetti-Valentini 2014; EC 2014b). Crédit Agricole had remained a major shareholder of BES from the early 1990s and reported a EUR 708 million (USD 950 million) loss in the second quarter of 2014 owing to its ownership in the Portuguese bank (Reuters 2014b). In May 2014, Crédit Agricole and ESFG (holding company of the ES family) jointly held 47% in BES through a holding company called Bespar (Reuters 2014a). In May 2014, they gave up their stakes in Bespar and, after BES issued new shares in BES in June 2014, Crédit Agricole and ESFG were left with individual stakes of 15% and 25% in BES respectively (Reuters 2014a)., a large French private bank, was the second largest shareholder in BES (Benedetti-Valentini 2014).

In 2014, BES was the second largest private bank in Portugal, with assets of over EUR 80 billion (USD 97.6 billion)FPer Yahoo Finance, EUR 1 = USD 1.22 on December 31, 2014. and 10,000 employees across 25 countries (EC 2014a).

BES had a market share of 11.5% of total deposits from the residents of Portugal, and 31% of financing of the insurance and financial sector. A disruption in BES’s financing activities would have had a significant systemic effect in Portugal (World Bank 2016).

In May 2014, KPMG’s external audit report noted irregularities in the accounts of ES and stated that the group is in “serious financial condition” (Kowsmann 2014a). Between June and August 2014, BES’s shares had dropped by 89% due to financial concerns (see Figure 6) (BBC 2014b).

On July 30, 2014, BES unexpectedly announced EUR 3.5 billion (USD 4.8 billion) in losses largely due to improper loans made to other affiliates of the ES group, dropping its Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio to 5% and breaching minimum regulatory requirements (BOP 2014d; Minder 2014b). BES had suffered from EUR 1.5 billion in unexpected losses from operations conducted in the first half of 2014 and had not previously reported this to the external auditor (World Bank 2016). Ricardo Espírito Santo Salgado, who ran BES for more than two decades starting from 1991, stepped down in May 2014, was held in custody in July 2014 for money laundering and tax evasion charges, and ordered by a judge to post bail of EUR 3 million (BBC 2014a; Ewing and Bray 2014; Minder 2014a).

In September 2013, the BOP initiated a ring-fencing policy for BES with respect to other companies in the ES group, after its ETRICC (Horizontal Review of Credit Portfolio Impairment) process, involving an audit of nonfinancial companies. This BOP policy was reinforced as ES group companies started to default. As of December 2013, external auditors KPMG and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) had confirmed the setup of a provision of EUR 700 million of capital to ESFG (Costa 2014b). On June 16, 2014, BES raised EUR 1.05 billion via a public markets offering from the issuance of 1.6 billion new common shares (BES 2015d).

On August 3, 2014, the BOP announced that it was applying a resolution measure to BES and transferring its good assets, customers, and operations to Novo Banco (a bridge bank), while protecting depositors and senior, unsubordinated bondholders. The Resolution Fund also announced its purchase of EUR 4.9 billion in common shares in Novo Banco, representing a 100% ownership stake in the bank (see Figure 2) (BOP 2014d). The BOP also transferred EUR 3.5 billion of Government Guaranteed Bank Bonds (GGBB), which the BES had issued under the Portuguese Guarantee Scheme to Novo Banco to strengthen the liability side of its balance sheet (EC 2017b). The bad assets and liabilities associated with the ES group were to remain in the residual entity, which was the bad bank under liquidation, with all losses to be borne by the equity and subordinated debt holders of BES (see Figure 1) (BOP 2014a). The Resolution Fund was to receive a EUR 3.9 billion loan from the Portuguese state and would also be funded by EUR 1.07 billion of contributions from banks in Portugal (EUR 700 million from eight participating banks and EUR 365 million of past contributions) (Machado 2019). At the time, the authorities stated that they expected the proceeds from the sale of Novo Banco would be used to compensate the Resolution Fund (Kowsmann 2014b).

Figure 1: Major Equity Holders of BES as of July 30, 2014

Sources: BES 2014a; Benedetti-Valentini 2014; EC 2014b.

Sources: BES 2014a; Benedetti-Valentini 2014; EC 2014b.

The next day, August 4, 2014, the European Commission (EC) approved the capital injection and creation of the bridge bank. The EC declared that the BOP’s actions were in line with State Aid rules, justified by the need to restore financial stability and avoid adverse systemic risks (EC 2014a). The BOP communicated the costs of a disorderly resolution of BES to the EC in the range of EUR 16–28 billion in losses, and up to EUR 18 billion from the Deposit Insurance Fund to cover insured deposits (Albuquerque and Branco 2016; EC 2017b).

In December 2014, Apollo Global, Banco BPI, and Banco Santander, were reported by the Wall Street Journal as interested parties to purchase Novo Banco with deposits of EUR 25 billion and a loan portfolio of EUR 32 billion (see Figure 2) (Kowsmann and Patrick 2014). In early September 2015, Novo Banco reported losses of EUR 252 million for the first half of the year due to costs associated with writing off loans received from BES. The BOP missed its own deadline to sell the Novo Banco, with the New York Times reporting that the potentially interested bidders included Anbang Insurance Group, Apollo Global, and Fosun International (Minder 2015). On September 15, 2015, the board of directors of the BOP suspended the sale process of Novo Banco due to the unsatisfactory three binding offers received, and other significant uncertainties including potential capital increases from the European Central Banks’s (ECB) prospective stress tests of the bank (BOP 2015a).

The ECB Banking Supervision stress test highlighted a capital shortage of EUR 1.4 billion at Novo Banco in the adverse scenario (BOP 2015b). Novo Banco passed the stress test in the baseline scenario with a CET1 ratio of 8.24% but fell short in the adverse scenario with a CET1 ratio of 2.43% versus the 5.5% passing threshold (BOP 2015b). Novo Banco committed to focusing on core business activities and reducing exposure to unprofitable business areas. In December 2015, the EC approved the extension of the Portuguese state guarantee to the bonds of Novo Banco at a value of EUR 3.5 billion, which were originally placed at BES in 2011 and 2012 (BOP 2015c). Novo Banco continued to report losses due to provisioning related to loan impairments, and disclosed losses of EUR 1.0billion in 2015, EUR 837 million in 2016, and EUR 290 million for the first half of 2017 (EC 2017b).

The bad bank BES reported a full year loss of EUR 9.2billion for 2014, loss of EUR 2.6 billion for 2015, and reported assets at less 3% of liabilities as of December 31, 2015. The BOP retransferred five issues of senior unsubordinated debt worth EUR 2.2 billion from Novo Banco to BES which was accounted for in the reported financials for 2015 (BES 2015c). The retransfer effectively imposed a total loss on the holders of these bonds, and later in 2016 led to legal action against the BOP by 14 institutional asset managers, including BlackRock and PIMCO (Hale and Arnold 2016).

At the time of the retransfer, Novo Banco had EUR 5.4 billion of senior unsecured debt among its liabilities (Reis and Almeida 2015). This move led to uncertainty and volatility in the broader markets for senior unsecured debt issued by European banks, as investors became concerned that this debt was also bail-in-able under the post-crisis regulatory regime (see Figure 8) (Hale 2016). As per the EU regulatory framework, senior debt is bail-in-able, which created the legal basis for the retransfer of the select senior bonds. In July 2016, the ECB revoked the ability of BES to function as a banking entity, leading to effective insolvency and liquidation of the legacy bad bank (BES 2016a).

In October 2017, the Resolution Fund sold 75% of Novo Banco’s equity to Lone Star, an American private equity fund, through Nani Holdings (Novo Banco 2015). The Resolution Fund did not receive anything for the EUR 4.9 billion in capital it had invested so far; however, it retained a 25% stake in Novo Banco to allow for potential inflows from its sale in the future. Lone Star agreed to invest EUR 1 billion of new capital into Novo Banco (Wise 2017).

However, Portuguese authorities also signed a Contingent Capital Agreement (CCA) with Lone Star, under which the state could compensate Lone Star up to EUR 3.9 billion to cover any losses related to a portfolio of legacy nonperforming loans (NPLs), in the event its Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio fell below 12%. The total amount authorized under the CCA corresponded to 75–95% of the gross book value of assets covered by the agreements (EC 2017b).

António Costa, Portugal’s prime minister, stated that choosing to nationalize Novo Banco would have cost the taxpayer an additional EUR 4.0 billion–4.7 billion upfront, and exposed the state to “limitless” liabilities down the road if the bank’s losses turned out to be even worse than expected. In contrast, the CCA exposed the state to costs on a contingent basis, which it booked over time, and capped its exposure at EUR 3.9 billion. Lone Star was restricted from paying dividends for a period of five years, to ensure that the income from asset sales would build Novo Banco’s capital (Wise 2017).

The Portuguese state also committed to providing a capital backstop, approved by the EC in 2017, in addition to the contingent capital agreement. The EC’s 2017 decision noted that the trigger for the state to provide aid under the capital backstop would be if the total capital of Novo Banco “falls below the SREP total capital requirement;” SREP is the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process, in which European supervisors evaluate banks’ capital and risks and assign an individual capital requirement for each bank every year. Specifically, the EC would deem it appropriate for the state to provide aid under the capital backstop “to the extent necessary to ensure the solvency of Novo Banco in the Commission’s adverse scenario.” (EC 2017b, 25).

At the end of 2021, Novo Banco’s minority shareholders comprised 24.61% held by the Resolution Fund, 1.56% held by the Directorate General for the Treasury and Finance, and 73.83% held by Lone Star (Nani Holdings). As per the deal with Lone Star, any conversion of rights instruments by the Portuguese state would only lead to a dilution in the shareholding of the Resolution Fund, and not affect Lone Star’s 75% holding. As a result, by the end of 2022, the Resolution Fund’s holding in Novo Banco reduced to 19.31%, the Treasury’s holding increased to 5.69%, and Lone Star’s holding was back to 75%. The latest annual report noted that the Portuguese state could have an effective stake of 22.1% in Novo Banco, at the expense of further dilution for the Resolution Fund. The share increase for the Treasury can be attributed to the completion of rights conversions for net negative results and tax credits accumulated by Novo Banco between 2015 and 2020 (Novo Banco 2023b).

In February 2023, Portugal’s Finance Ministry announced that the European Commission had declared the end of the restructuring process and the end of its ongoing monitoring of the implementation of the resolution of Novo Banco. The GOP called the EC announcement “the end of a very important stage for the stabilization of the national financial system.” (GOP 2023). The BOP stated in a separate statement that the restructuring of Novo Banco in 2014 and the contingent capital agreement in 2017 were essential for the survival of the bank. The BOP argued that the completion of the restructuring process was “a further indicator that Novo Banco will not need to request any further payments from the Resolution Fund under the [CCA].”(BOP 2023, 1). The Finance Ministry and BOP also both noted that the end of EC involvement meant that the Portuguese state was no longer committed to provide the public capital backstop in an extreme scenario (BOP 2023). The Portuguese state and the Resolution Fund continue to hold a joint 25% stake in Novo Banco, including 12% held by the Treasury and 13% held by the Resolution Fund, as per an investor presentation from November 2023 (Novo Banco 2023c).

As of November 2023, Novo Banco had received EUR 3.4 billion under the CCA, and had an additional EUR 485 million available to fund losses if its CET1 ratio drops below 12%. The CCA is in place until December 2025, and can be extended under specific conditions by an additional one year. Novo Banco remains subject to a dividend ban and has a servicing agreement with the Resolution Fund until the maturity of the CCA. Novo Banco reported that its net nonperforming asset (NPA) ratio had fallen from 12.2% in 2017 to 0.7% in the third quarter of 2023. Novo Banco’s CET1 ratio was 16.5%, strongly above the 12% CCA trigger (Novo Banco 2023c). Novo Banco’s CEO Mark Bourke declared that the bank would be operationally ready for an initial public offering (IPO) in the first half of 2024 (Reuters 2023). In December 2023, the DBRS rating agency upgraded the long-term debt of Novo Banco by two notches due to notable improvements in earnings and capital (Novo Banco 2023a).

Figure 2: Timeline of the Resolution of BES

Source: Author’s analysis.

Source: Author’s analysis.

Observers praised the government’s speedy decision in 2014 to create the Novo Banco bridge bank, with nearly all of BES’s legacy assets, while leaving most non-deposit liabilities in a bad bank, the legacy BES entity, for liquidation and imposing total losses on equity, subordinated debt, and ES-linked liabilities. Virtually all of the assets remained in the bridge bank to manage.

The BOP’s decision to impose losses on a selected group of institutional investors with senior creditor claims in December 2015 was subject to substantial criticism and legal challenge. Moreover, the initial valuations of the bridge bank’s assets proved over-optimistic. It took three years to sell the bank, a year longer than planned, and the amount of the state loans ultimately grew to nearly twice the original estimate. The EC’s 2014 decision approved EUR 4.9 billion in State Aid and stated that “no additional capital injection can be provided to the Bridge Bank in the future.” (EC 2014b, 11) Three years later, the EC approved up to EUR 3.9 billion in additional aid (EC 2017b).

The IMF noted in 2015 that the financing arrangement between the Portuguese government and the Resolution Fund potentially added a considerable burden on a concentrated and unprofitable banking system. The IMF suggested a revised repayment schedule for the government’s loan, with a longer-term horizon to allow the banking system to absorb the costs of the resolution (IMF 2015).

In 2015, Fitch Ratings stated that if the sale price for Novo Banco was lower than the size of the loan to the Resolution Fund, the losses would have to be borne by the Portuguese banking system. Fitch noted further that Caixa Geral de Depósitos and Banco Comercial Português were the largest contributors to the Resolution Fund, but the potential costs to each Portuguese bank would depend on each bank’s capital and profitability levels (Fitch Ratings 2015).

In 2016, Fitch Ratings stated that the BOP’s 2015 decision highlighted the risk of retransfer of bonds in bridge banks until the resolution is concluded. It was stated that the lengthy time frames for resolutions required the EU to reassess its strategy to deal with failing banks. Fitch noted that the BOP had been unsuccessful in selling Novo Banco to private buyers, and viewed the retransfer of bonds as a “restricted default” by Novo Banco (Fitch Ratings 2016).

Albuquerque and Branco, two attorneys in private practice, concluded in the International Banking Law and Regulation Journal, prior to the announcement of the sale of Novo Banco to Lone Star, that the resolution procedures applied to BES were successful in saving all the depositors of BES, limiting damages from BES’s failure, and ensuring stability in the Portuguese financial system. The authors noted that the legal transfer of the bank’s assets was able to ensure a quick transition and allowed to continue essential services of the bank. The authors also mentioned that the structure and the size of the bridge bank may have been too complicated for a speedy resolution, as the assets and liabilities were difficult to evaluate, and the capital concerns of the institution increased over the two years of attempted sale of Novo Banco (see Figure 7 in the Appendix). The authors declared that the BOP was forced to “rearrange the perimeter” or make retransfers of assets across the good and bad banks, which is an important resolution tool, but opens the room for arbitrary treatment of bondholders. Overall, the authors noted that depositors suffered no losses, and the viable parts of BES were saved when transferred to Novo Banco (Albuquerque and Branco 2016).

The Financial Times stated that the BOP’s decision to impose losses on senior bondholders in December 2015 was conducted in an “extremely convoluted manner” and led to legal cases from BlackRock and PIMCO alleging unequal treatment of senior creditors and discrimination against international investors. The same report concluded that the Novo Banco case would provide an important precedent for cases that in “public interest” overwhelm contractual claims provided by legal processes (Hale 2018a).

In 2018, the British Supreme Court dismissed Goldman Sachs’s claims for compensation over a loan to BES (Reuters 2018). The Supreme Court ruled that Novo Banco was not bound by English jurisdiction, and that any challenges to the restructuring measures by Portuguese authorities in 2014 should be dealt with by Portuguese courts. The British High Court had ruled in favor of Goldman Sachs in 2015, but that decision had been overturned by the Court of Appeal. The Supreme Court upheld the findings of the Court of Appeal (McNeill 2018).

The World Bank published a case study on the BES resolution in 2016, prior to the announcement of the sale of Novo Banco to Lone Star, authored by a legal expert in the BOP’s resolution unit. The case study noted that the transfer of senior liabilities was “expressly provided for in the legal framework and in the original resolution decision of August 3, 2014.” (World Bank 2016, 56)

The World Bank report also noted that when using the bridge bank tool in resolutions, it is essential to have a follow-up implementation plan. There must be coordination between the resolution authority and the management of the bridge bank, to ensure that the bridge bank has access to liquidity, payments, and clearing systems. The BRRD emphasizes the mutual recognition of crisis management measures and limits the ability of creditors to prevent or challenge the transfer of assets as per the local laws of EU member states. The UK Court of Appeal ruled that the UK was obliged to recognize the transfer of assets from BES to Novo Banco, and a debt claim by investors could only be pursued after a decision by the courts in Portugal (World Bank 2016).

The World Bank also highlighted the importance of ex ante and ex post valuations by an independent adviser to accurately determine the extent of burden sharing by equity and bondholders and ascertain appropriate transfer pricing. The BOP had to retransfer non-subordinated bonds back from Novo Banco to BES to adjust for the initial overvaluation of assets. This case also highlighted the challenges in the sale process of a bridge bank out of resolution since the Resolution Fund continued to maintain a minority stake in Novo Banco beyond the initial two-year sale deadline (World Bank 2016).

In 2017, the EC’s credit file review highlighted that not only did the past lending practices of BES lead to the bank’s decline, but also that Novo Banco had done little to remedy the faulty lending practices. The EC noted deficiencies such as lack of cash flow analyses, insufficient protection in loan agreements, inconsistent collateral valuations, documentation inaccuracies, and inadequate credit risk assessment (EC 2017b).

The chief legal counsel of the BOP, Pedro Machado, stated in 2019 that the BOP’s resolution in 2014 was broadly in line with the BRRD, with access only to the sale of business and the bridge bank tools. It was further noted that BES’s resolution presented cross-border challenges which served as impediments in quickly creating a resolution action plan. The author concluded that cooperation between the resolution authorities, both inside and outside the EU, would be helpful to implementing a successful resolution action plan. It was also highlighted that resolution plans are inherently subject to legal risk, due to the high number of stakeholders involved and that some are adversely affected in an attempt to maintain overall stability. The resolution authority would gain from enhanced discretion in the legal framework while implementing plans to minimize damages from bank failures (Machado 2019).

In the learnings from the BES resolution, Machado noted that in certain cases the objectives of preserving financial stability and protecting taxpayer funds are in conflict. Restrictions on banks in resolution, such as sale deadlines and limits to disrupt competition, can adversely affect the ability of the bank to return to viability and thereby effectively increase the costs of resolution (Machado 2019).

Deloitte, and other special auditors of Novo Banco had highlighted the difficulties in recovering assets from troubled loans in reports since 2020. Novo Banco’s Monitoring Committee had also previously hired international detectives to improve loan recoveries from defaulting customers, but without much success (Ribeiro 2022).

In 2021, Fitch Ratings stressed that clarity on further capital injections for Novo Banco would help clear uncertainty and help the entire Portuguese banking sector. Fitch noted the questions by opposition parties in the Portuguese Parliament on the cost of public support to Novo Banco and the need for additional inquiry by the Parliament and Court of Audit. The prime minister and finance minister emphasized the intentions of the Government to meet the obligations of the CCA (Fitch Ratings 2021).

In 2022, a member of the European Parliament, João Pimenta Lopes, noted that after Novo Banco’s sale to Lone Star, the bank disposed legacy assets inherited from BES at a steep discount and needed to access the CCA (Lopes 2022). In a written response, the EC’s vice president Margrethe Vestager clarified that capital requirements for Novo Banco were determined by the authorities based on National Portuguese Law, and that the EC was monitoring compliance on commitments by the Portuguese government (Vestager 2022).

In the same year, the Portuguese Communist Party presented the case that eight years since the application of resolution to BES, and five years after the sale to Novo Banco, the costs to the country have been EUR 9 billion. The report by the Court of Auditors on Novo Banco from 2021 is cited to reflect the lack of effective control measures in the disposal of assets in the capital mechanism (PCP 2022).

Portugal’s State and Resolution Fund continues to hold a joint 25% stake in Novo Banco with a book value of EUR 1.1 billion (12% held by the GOP and 13% stake held by the Resolution Fund) (Novo Banco 2023c). Novo Banco is expected to complete an IPO in 2024, which could allow the Portuguese state an additional opportunity to monetize its holdings (Reuters 2023).

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

1

The board of directors of the BOP declared at an extraordinary meeting on August 3, 2014, that urgent steps were being taken to “safeguard the financial soundness” of BES, to protect the bank’s depositors, and to maintain the financial stability of the Portuguese financial system. The BOP was presented the resolution “for safeguarding the interests of taxpayers” and in “clear and urgent public interest,” thereby ensuring that public recapitalization could be avoided and that it creates a path for the sale of the new bank to private investors (BOP 2014a, 5). BOP estimated that a disorderly resolution of BES could generate EUR 19.0–28.0 billion in losses, including a EUR 9.0–18.0 billion payout by the Deposit Guarantee Fund to reimburse covered deposits. In approving the government support to the bank, the EC also noted that immediate resolution or bankruptcy of BES, rather than an orderly winddown, would lead to a “fire sale of assets” (EC 2014b).

BES suffered from deposit flight of EUR 1 billion to 1.9 billion in July 2014 (EC 2014b). On July 31, 2014, BES notified the Portuguese Securities Market Commission (Comissão do Mercado de Valores Mobiliários, or CMVM) of losses of EUR 3.6 billion for the parent ES group for the first half of 2014. BOP noted that the losses at BES were EUR 1.5 billion larger than the bank’s disclosure on July 10, 2014. BES had a market share of 20% in Portugal, comprising 11.5% of the total deposits in the system. BES funded 31% of the financing and insurance activities in Portugal (BOP 2014a). BES had total assets of EUR 76 billion and deposits of EUR 37 billion at the end of June 2014 (EC 2014b).

BOP declared that the losses at BES were “exceptional in nature” and were incurred by increasing exposure to other entities of the ES group, despite the BOP’s guidance (BOP 2014a, 2). The consolidated CET1 and total capital ratios for BES at 5.1% and 6.5% were lower than BOP’s minimum regulatory requirements of 7.0% and 8.0%. On July 31, 2014, BES notified BOP that it would be unable to implement a recapitalization plan in the stipulated time period. BES was in a “severe liquidity shortfall”, and lacked eligible collateral to access funds through monetary policy operations (BOP 2014a, 3).

On August 1, 2014, BES’s use of Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) from the ECB reached EUR 3.5 billion, as the bank had exhausted its own capital buffer (BOP 2014a; IMF 2015). That day, the Governing Council of the ECB suspended the bank’s monetary policy counterparty status and asked the bank to repay EUR 10 billion in credit by the close of August 4, 2014. The ECB’s decision to suspend the counterparty status of BES forced the bank to seek emergency liquidity assistance from the BOP (BOP 2014a). The Portuguese regulators assessed various options to resolve the problems at BES over the weekend of August 2–3, 2014 (EC 2014b).

The BOP submitted an operational and financial resolution plan for BES to the EC on August 3, 2014, which involved the creation of a bridge bank. Most assets, all depositors, and senior liabilities were transferred to the bridge bank, while the remaining assets—mostly loans to ES affiliated companies—and subordinated liabilities remained in the legacy institution to be resolved (EC 2014b). The bridge bank or Novo Banco would allow the customers and depositors of BES to continue operations without any disruptions (BOP 2014d).

The Resolution Fund would inject EUR 4.9 billion of new equity capital to fund Novo Banco. The BOP’s plan stated that, since state resources would only be used to finance the Resolution Fund rather than for direct capitalization, the resolution would protect the taxpayer from losses (BOP 2014a). The BOP noted that the Resolution Fund was supported by the Portuguese financial sector (BOP 2014d). Novo Banco was created as a temporary credit institution as per an order by the Ministry of Finance, following a proposal by the BOP (EC 2014b). In December 2014, the BOP acting as the resolution authority for Novo Banco, extended the maturity and government guarantee by one year of EUR 3.5 billion of GGBB transferred from BES to Novo Banco (EC 2015).FBES had issued GGBB under the Portuguese Guarantee Scheme between 2011 and 2012 with a maturity of three years (EC 2015). Portuguese authorities were only allowed to use the GGBB to benefit a solvent institution, and Novo Banco had revealed a capital shortfall in the adverse scenario in November 2014 (EC 2015). As per legal requirements, the granting of such an extraordinary guarantee by the Portuguese state would require a revision of the interest rate on the bonds (EC 2015). The coupon rate for these bonds was revised from a spread of +12% above the Euribor 3-month rate, to +1.5% in 2014 and +0.9% in 2015 (EC 2015). The BOP stated that maintaining a state guarantee on the GGBB was essential to ensure adequate collateral for liquidity at BES (EC 2015). The EC noted the prolongation of the GGBB was as per Article 32(4)(d)(ii) of Directive 2014/59/EU (EC 2015). This article notes that extension of a state guarantee on newly issued liabilities does not qualify the receiving institution to be deemed failing or likely to fail (EC 2015).

The BOP appointed PriceWaterhouseCoopers Sociedade de Revisores de Contas, Lda (PwCSROC) to provide an independent valuation on BES within 120 days of the resolution announcement (BOP 2014a). Prior to the BOP’s resolution plan, BES had hired Deutsche Bank as a financial advisor to formulate a potential private sale. Due to BES’s inability to present a credible private solution, BOP chose resolution as the only reasonable option to implement an immediate action plan, limit the exposures to the ES group, and clean up the balance sheet of BES. The BOP also found that outright sale of the BES business was not feasible over the weekend since any investor would require time for adequate assessment (Machado 2019).

The independent valuation by PwCSROC led to significant adjustments in the net book value of assets on the balance sheet of BES at the time of resolution (World Bank 2016). The report by PwCSROC indicated that the value of BES’s consolidated assets were EUR 4.9 billion, including deferred tax and other tax contingencies of EUR 1.2 billion (BOP 2014e). In line with the no creditor worse off (NCWO) principle, the BOP appointed Deloitte Consultores, S.A. (Deloitte) to estimate the recovery for all creditors in the scenario that BES had been liquidated prior to the application of the resolution actions. Deloitte concluded that in the liquidation scenario, equity and subordinated debt holders would have zero recovery, and unsubordinated, unpreferred claims would have a recovery rate of approximately 32%. Any creditor who received a lower recovery rate in resolution, compared to the liquidation scenario, would receive compensation from the Resolution Fund (World Bank 2016).

The assets, liabilities, and off-balance sheet items were transferred at book value from BES to Novo Banco, which were to be confirmed by an audit. Based on this valuation, the capital shortfall of Novo Banco was estimated at EUR 4.9 billion in 2014 (BOP 2014a). The legal advice to the BOP for the scope of the sale of Novo Banco was provided by Vieira de Almeida & Associados and Allen & Overy (BOP 2016).

In 2021, the GOP appointed Deloitte & Associados, SROC to conduct an independent audit of Novo Banco, following up on the previous audit in August 2020. The BOP committed to sharing the special audit report with the ECB, as the supervisor of Novo Banco under the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), and Portuguese regulators including Securities Market Commission and the Insurance and Pension Funds Supervisory Authority (BOP 2021).

Part of a Package

1

Novo Banco received several capital injections from the Resolution Fund between 2014 and 2021 to help stabilize the bridge bank, as the BOP conducted a private auction of the bank and its assets (Gupta, forthcoming). In August 2014, the Resolution Fund provided EUR 4.9 billion to Novo Banco in exchange for common shares of the bank (EC 2014b). The Resolution Fund garnered the capital from a loan of EUR 3.9 billion from the Portuguese state, a loan of EUR 700 million from eight Portuguese banks, and EUR 365 million of prior contributions from the banking system between 2013 and 2014 (Machado 2019). The private banking system effectively contributed slightly over EUR 1.0 billion of the total EUR 4.9 billion capital injection into Novo Banco.

In 2017, Novo Banco and the Resolution Fund committed to a Contingent Capital Agreement (CCA), which required the Resolution Fund to provide up to EUR 3.9 billion of additional capital injections (Resolution Fund 2014). Between 2018 and 2021, the Resolution Fund provided a total of EUR 3.4 billion in capital injections to Novo Banco (see Figure 3).

Legal Authority

1

The BOP took the resolution measures under Article 146(1) of the Legal Framework of Credit Institutions and Financial Companies (Regime Geral das Instituições de Crédito e Sociedades Financeiras, or RGICSF) and provisions of Article 103 (1) (a) of the Administrative Procedures Code (Código do Procedimento Administrativo) (BOP 1992; BOP 2014a).

In August 2014, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) was active but had not been adopted into national legislation in Portugal. Portugal enacted its own resolution regime, the RGICSF, in 2012. Through this national resolution regime, the BOP was able to utilize the sale of business tool and the bridge institution tool. The RGICSF did not provide for a bail-in tool but was largely very similar to the BRRD. The selection of assets and liabilities to be transferred to Novo Banco utilized the guiding principle of ascribing first losses to the equity holders of an institution in resolution, followed by the creditors in equitable conditions. The burden sharing was guided by not only the national resolution law, but also the State Aid rules enforced in the EU since 2013 which requires equity and bond holders to bear losses before State Aid is provided (World Bank 2016).

Novo Banco was set up for an intermediate time period as per Article 145-G (3), (5) , and received the operating unit of BES under Article 145-H (1) of the existing resolution framework (RGICSF), approved by Decree-Law No 298/92. Following are the other provisions of the RGICSF that were used in the resolution disclosure (BOP 2014a):

- Article 145-B states that shareholders would bear the first losses at an institution

- Article 145-D (2) to appoint the board of directors and board of auditors of Novo Banco

- Article 145-H (5) allows the BOP to retransfer any assets, liabilities, and off-balance sheet items between BES and Novo Banco at any time

- Article 145-I states that proceeds from the sale of the new bank will be returned to the original credit institution

- Article 145-G states that Novo Banco is set up for an indeterminate time

- Article 153-B states that the Resolution Fund will be the sole equity owner of Novo Banco

- Article 141(1), (2) allows the BOP to impose corrective actions on BES, including prohibiting the bank from taking deposits and making any investments other than those necessary for preservation of the value of assets (BOP 2014b)

The BOP was also acting under Article 17-A of the BOP’s Organic Law with respect to the transfer of assets, liabilities, and off-balance sheet items from BES to Novo Banco. Novo Banco was to also comply with management criteria to maximize the value of the bank and maintain low levels of risk, as per Article 15 of the BOP Notice No 13/2012 (BOP 2014a).

The BOP transferred EUR 3.5 billion of State Guaranteed Bonds of BES to Novo Banco in line with the 2013 Banking Communication, which are State Aid rules set by the EC for banks after the financial crisis (EC 2014b).

In December 2015, the BOP decided to retransfer liabilities with a nominal value of EUR 2 billion related to non-subordinated bonds of BES to the bad bank. The BOP’s ability to conduct this retransfer was deemed necessary to ensure that losses at BES were absorbed by shareholders and subordinated debt holders, rather than the Resolution Fund (World Bank 2016). The Novo Banco case was referred to a precedent where the public interest clause was used to override contractual claims or legal proceedings (Hale 2018a).

An interesting difference between the BRRD and the Portuguese resolution regime is that the latter allows the creditors of an institution in resolution to be converted into shareholders of the bridge institution. This financing structure allows the Resolution Fund to provide less equity capital upfront to the bridge institution (World Bank 2016).

Portugal’s Central Department of Investigation and Penal Action (DCIAP) indicted 25 individuals in July 2020, including the former president of the ES group under allegations of fraud, money laundering, and corruption. In May 2023, the Criminal Court in Lisbon began to hear the BES case, which had garnered 242 inquiries and over 300 complaints from within Portugal and from abroad. The instructional debate in court included key witnesses in former Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho, former BOP governor Carlos Costa, and José Maria Riccardi, president of ES investments (Fernandes 2023a).

Administration

1

The board of directors of the BOP formulated a resolution action plan for BES at an extraordinary general meeting on August 3, 2014 (BOP 2014a). The proposal by the BOP was adopted by a Ministry of Finance decree which created Novo Banco, with the Resolution Fund as the sole equity owner (EC 2014b). The BOP provided technical and administrative services to the Resolution Fund, with the Fund’s general secretary forming a part of the BOP’s staff (Resolution Fund n.d.). The BOP was officially responsible for the new management of Novo Banco, while the shares of the bridge bank were held by the Resolution Fund.

The BOP was to appoint the board of Novo Banco, after a proposal from the management committee of the Resolution Fund. The board of directors and auditors were to remain in office for two years, and renewable by one year. The board of directors was to have a maximum of 15 members, with the chair and vice-chair appointed by the BOP, after proposals from the Resolution Fund. The board of directors of Novo Banco was required to meet at least once every month, and the board of auditors were to meet once every two months. Novo Banco was to be managed in a “commercially neutral manner,” or limit aggressive competitive strategies versus other European credit institutions, thereby providing new loans and deposits only at the banking system’s average rates. BOP was to decide on winding up Novo Banco, after the sale of the bank and returning proceeds to the Resolution Fund (BOP 2014a).

The BOP initially appointed the administration of the legacy bad bank for a period of one year in August 2014, which was extended by another year in August 2015. The BOP had also imposed a series on corrective measure on the legacy bad bank for the preservation of assets and improvement of compliance with prudential rules. The legacy bad bank was allowed to temporarily maintain its banking license, although at a deeply restricted level (BES 2016b). Luís Máximo dos Santos, the current vice governor of the BOP, was appointed as the president of the board of directors of BES between 2014 and 2016, and later served as the head of the Resolution Fund from 2017 to now (Neutel 2023).

In August 2014, the Bank of Portugal appointed a new board of directors and statutory supervisory body for Novo Banco, after a proposal from the management committee of the Resolution Fund (as per Article 145-G of the RGICSF) (Novo Banco 2015).

Governance

1

The Resolution Fund was initially created in 2012 to assist the BOP, as the national regulation authority in the execution of resolution procedures. After the EU introduced the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) in August 2016, the Resolution Fund became responsible for providing funding for financial measures outside the scope of the SRM. The Resolution Board is expected to submit its annual accounts to Portugal’s Ministry of Finance by March 31 every year (Resolution Fund n.d.). As of December 2017, the Resolution Fund had negative equity capital of EUR 5.1 billion (Machado 2019).

Novo Banco was supervised by the BOP and had to comply with legal and regulatory laws as per the BOP-approved bylaws of Novo Banco (BOP 2014d). The SSM of the ECB would be the lead supervisor of Novo Banco once implemented (EC 2015). The EC initially declared that the assets of Novo Banco should be sold within 24 months of the resolution decision, with the unsold assets to be wound down (EC 2014b). The EC later stated that the BOP committed to initiating the sale of Novo Banco by January 15, 2016, without an explicit date to complete the sale (EC 2015). The Single Resolution Board (SRB) was to be the centralized decision-making body for resolution in Europe from January 1, 2016 (Hale 2018a). Hence, there was a period in late 2015 where European resolution powers were effectively with the BOP (Hale 2018a).

The resolution of BES by Portuguese authorities took place before the BRRD came into force, and hence the sale process of the Novo Banco was to be governed by Portuguese resolution laws (EC 2017a).

All the commitments related to Novo Banco were applicable mutatis mutandis to the bad bank (EC 2014b). The banking license of the bad bank would be revoked after the sale of Novo Banco. The bad bank was expected to reduce its balance sheet exposure by 20 to 30%, could not generate new business, would enter liquidating proceeds after its license was revoked, and would ensure maximizing recoveries. The Commercial Court of Lisbon’s liquidation committee was to ensure the proper liquidation of the bad bank (EC 2014b).

The Portuguese regulators had to ensure to the EC that the resolution plan was (1) well targeted, (2) necessary and limited to minimum cost, and (3) designed to limit negative knock-on effects to the real economy. Portuguese regulators had to file regular reports with the EC as per section 6.5 of the 2013 Banking Communication (EC 2014b).

An independent monitoring trustee was appointed to Novo Banco by the Resolution Fund, after a proposal from the BOP and approval by the EC. The monitoring trustee was to track compliance with all of the commitments made by Novo Banco, the legacy bad bank, and BOP to the EC. The EC could ask Novo Banco or the legacy bad bank for explanations and clarifications as the resolution proceeded. The monitoring trustee would be remunerated by the legacy bad bank. The Portuguese regulators were to submit two proposals for trustees to the EC within four weeks of the start of the resolution plan. As per section 6.5 of the 2013 Banking Communication, the Portuguese government had to file regular reports to the EC, including consulting the EC for the appointment of the monitoring trustee by the Resolution Fund (EC 2014b).

In 2017, as per the CCA, Novo Banco had to alter its articles of association to include a monitoring committee of three individuals, two members appointed by the Resolution Fund and one independent member. The monitoring committee was to attend Novo Banco’s board meetings without voting rights (EC 2017b). In 2023, the EC declared an end to the restructuring of Novo Banco after receiving a report of the monitoring trustee, an independent agent to assess the execution of the resolution plan. The monitoring trustee’s final report was prepared after audited accounts for Novo Banco for the full year 2022 (GOP 2023). One member of the monitoring committee had to be a registered chartered accountant (Novo Banco 2023b).

Communication

1

The BOP communicated the resolution for BES through press releases, annual report disclosures, governor speeches, financial stability reports, and EC State Aid disclosures. In September 2014, Portugal’s prime minister Pedro Passos Coelho emphasized that the sale of Novo Banco needed to be quick to keep risk mitigated, while ensuring the best possible terms of sale (Reuters 2014c). The future of the bad bank of BES was uncertain, including the ES group’s other businesses from the tourism, agriculture, and healthcare sectors. There were other concerns in the press that the Portuguese authorities had approved a capital raise of EUR 1 billion at BES in the month prior to the resolution plan, which coincided with the market capitalization dropping by 89% (BBC 2014b). Crédit Agricole’s CEO Jean-Paul Chifflet stated in August 2014 that the French bank felt that it was “misled by the family” that ran BES (BBC 2014c). He further describes the loans from BES to the ES group as “outside the . . . bank’s corporate governance” (Reuters 2014b). Portugal’s prime minister Antonio Costa stated that if Novo Banco was nationalized, the state would have to inject EUR 4–4.7 billion of additional capital and be exposed to unlimited liabilities (Wise 2017).

The CMVM chief Carlos Tavares told a parliamentary committee in 2014, that it had examined ES group companies several times over the past six years after finding abuses of confidence and insider information. KPMG has previously found that ESI (another parent company of BES based in Netherlands) had under-reported its liabilities and overvalued its assets, and described nearly EUR 6.4 billion of debt held on ESI’s books as an “atomic bomb” (Goncalves, Noonan, and Khalip 2014a, 7). The problems at ESI were disclosed in May 2014, when Salgado as CEO of ESI stated that the problems were due to “serious negligence,” rather than “willful misconduct” (Goncalves, Noonan, and Khalip 2014a, 8). It was also reported that Salgado approached the government of Portugal for a EUR 2.5 billion loan in June 2014, and had his request denied for the use of public funds.

In a speech, BOP governor Costa confirmed that the capital injection and resolution was to address the financial imbalance at BES. The dual goal of the resolution was stated by the governor as guaranteeing deposit protection and ensuring financial stability. Governor Costa emphasized that the Resolution Fund’s financial resources did not come from state resources but was funded from levies on the banking system and represented an integral part of the European financial stability model (Costa 2014a).

In November 2014, Governor Costa in a parliament inquiry speech stated that the “plan A” for BES involved immediate capitalization of the bank, with preferable recourse to private investors. Governor Costa discussed that BOP had various contingency or “plan B” scenarios in case the private solution was not implemented in time. The ECB governing council delayed the suspension of BES as a Eurosystem counterparty for 3 days on August 1, 2014, so that the BOP could submit a resolution plan over the weekend (Costa 2014b).

Additionally, the governor stated in the same speech that ESFG (the financial arm of the ES group) had been “subject to unparalleled balance sheet scrutiny” because of Portugal’s participation in the Economic and Financial Assistance Program since 2011 (Costa 2014b, 5).FIn May 2011, Portugal received a three-year loan of EUR 78 billion from a group of donors, including the EU. During the program, Portugal received (1) EUR 24.3 billion from the European Financial Stabilization Mechanism, (2) EUR 26.0 billion from the European Financial Stabilization Facility, and (3) EUR 26.5 billion from the IMF. The economic adjustment package required Portugal to implement structural reforms to boost growth and to reduce national deficits to 3% of GDP by 2013. The assistance program ended in June 2014. Portugal is subject to surveillance by the EC and ECB until 2026 or until at least 75% of the loans have been paid back (EC 2011). In July 2014, BES raised EUR 1.05 billion via a public markets offering from the issuance of 1.6 billion new common shares (BES 2015d). Governor Costa added that the BOP’s decisions with regards to the EFSG were to ensure public confidence, protect depositors, and maintain financial system stability (Costa 2014b).

BES disclosed its balance sheet as of August 2014 after one year on August 7, 2015, to account for the transfer values as established by BES’s board of directors and valuation reports by the external auditors. BES waited to provide the full year financials for 2014 to account for the changes in legal framework, and clarifications on the resolution provided by the BOP (BES 2015a; BES 2015b).

In December 2015, the BOP converted EUR 2.2 billion of senior liabilities of Novo Banco into liabilities of the bad bank, effectively writing them down. This action created uproar among senior bond investors and commentators, and later led to a lawsuit by 14 asset managers (Hale and Arnold 2016). Commentators in the Financial Times referred to the Novo Banco Case as a “debacle” and “saga,” while quoting BlackRock, which deemed the retransfer of senior bonds by the BOP as “unlawful” (Hale 2018a, 2; Hale 2018b, 1). This move also led to uncertainty in the senior unsecured debt markets, as investors became concerned that this debt was also bail-in-able (see Figure 8 in the Appendix) (Hale 2016, 6).

In the same month, the BOP clarified that the prospective buyers of Novo Banco were not receiving any tax bonus or special exception, contrary to media reports in Portugal. The BOP discussed that the treatment of deferred tax credits by the Portuguese tax system needed to align with the European system, and a final decision would be taken by the Portuguese government (BOP 2015d).

In July 2020, the BOP provided a clarification on the “capital backstop” safeguard with the ECB in 2017, stating that the BOP had not agreed to providing any capital injection to Novo Banco beyond the terms of the CCA. The capital backstop was a commitment by the Portuguese state to the EC to ensure viability of the bank in an adverse scenario and did not fall within the scope of powers of the BOP or Resolution Fund. The EC’s backing provides the “ultimate backstop” as the lender of last resort to the Portuguese state (BOP 2020).

Portugal’s Legislative Assembly had also filed an audit request to the Court of Auditors in October 2020 regarding the past retransfer of senior bonds. In 2022, the BOP responded to the Court of Auditors’ report, by stating that safeguarding public interest went beyond minimizing contributions to the Resolution Fund. The BOP further stated that the resolution measures protected Portugal's Treasury from liquidation scenarios for BES in 2014 , which would have had a significantly larger adverse impact on public accounts (BOP 2022).

The BBC reported in August 2014 that the BOP was splitting BES into a “good bank with healthy assets” and a “bad bank with riskier ones”, while quoting the BOP governor Costa on how the “plan carries no risk to public finances or taxpayers.” (BBC 2014b, 2). Other commentators have noted that the asset separation at BES was publicized through a good/bad bank lens to signal that Novo Banco was protected from the legacy exposures to the ES group, and to maintain the fundamental value of the asset book (Albuquerque and Branco 2016). The EC appropriately titled Novo Banco as a “bridge bank” with EUR 64 billion of assets, and the remaining BES entity as the “bad bank” with net assets of under EUR 1 billion (EC 2014b). The bad bank title may be inappropriate since several of the troubled assets remained with Novo Banco, as the bridge bank continued to report cumulative losses of over EUR 2 billion due to provisioning related to impaired loans (EC 2017b).

Source and Size of Funding

1

The Resolution Fund provided EUR 4.9 billion to Novo Banco in exchange for common shares of the bank. The Resolution Fund was to receive a EUR 4.5 billion loan from the Portuguese state (EC 2014b). As per the Resolution Fund’s disclosures, the Portuguese Treasury ultimately provided EUR 3.9 billion (IMF 2015; Resolution Fund 2014). A group of Portuguese credit institutions—Caixa Geral de Depósitos, Banco Comercial Português, Banco BPI, Banco Santander Totta, Caixa Económica Montepio Geral, Banco Popular, Banco BIC Português, and Caixa Central de Crédito Agrícola Mútuo—provided EUR 700 million to the Resolution Fund (Resolution Fund 2014).

The Resolution Fund had EUR 365 million of its own funds and a EUR 635 million syndicated loan from the banking sector. A part of the capitalization of the Resolution Fund was funded through the Bank Solvency Support Facility and was structured as a 24-month loan from the Portuguese state to the Resolution Fund, with increasing interest rates to incentivize the sale of the bridge bank. In the case that sale proceeds from Novo Banco are insufficient to reimburse the loan to the GOP, the Portuguese banking system would face either nonpayment of the EUR 635 million subordinated loan, or additional exceptional contributions to the Resolution Fund (IMF 2015).

When the government sold Novo Banco in 2017, it agreed to provide up to EUR 3.9 billion of additional capital injections through the Resolution Fund (EC 2017b). The Portuguese government extended the maturities on its loans to the Resolution Fund to 2046. Fitch Ratings noted that the additional capital requirements of the CCA meant that contributions from the Portuguese banking sector to the Resolution Fund would be spread out over several years. The Resolution Fund’s annual capital contributions were capped at EUR 850 million, and any additional requirements of funds could be accessed through a new loan or guarantee from the Portuguese government (Fitch Ratings 2017).

As per Figure 3, between 2018 and 2021, the Resolution Fund provided a total of EUR 3.4 billion in several additional capital injections in Novo Banco to cover capital shortfalls (Gupta, forthcoming).

On June 16, 2014, BES raised EUR 1.05 billion via a public markets offering from the issuance of 1.6 billion new common shares (BES 2015d).

Figure 3: Contingency Capital Agreement Drawdowns on the Resolution Fund for Novo Banco

Sources: Arnold 2018; EC 2017b; Fitch Ratings 2021; Goncalves 2021a; Goncalves 2021b; Novo Banco 2023c; Wise 2019.

Sources: Arnold 2018; EC 2017b; Fitch Ratings 2021; Goncalves 2021a; Goncalves 2021b; Novo Banco 2023c; Wise 2019.

Approach to Resolution and Restructuring

1

The BOP adopted the approach of separating assets and creating a bridge bank, Novo Banco, to resolve BES in August 2014. Select assets and liabilities of BES were transferred to Novo Banco, with the remaining parts of BES comprising the impaired assets labeled as the bad bank. Novo Banco received equity capital of EUR 4.9 billion from the Resolution Fund, with the fund receiving a EUR 4.5 billion loan from the Portuguese state. Novo Banco was to have a CET1 ratio in the range of 8–12% after its capital injection by the Resolution Fund, with the capital amounts determined by the BOP (EC 2014b).

The goal of the resolution plan was to restore the viability of Novo Banco in a going concern and restructure its operations while minimizing overall losses or costs to the taxpayer. The bridge bank had to be sold by December 31, 2016, as per the original resolution plan. The overall goal of the strategy was to ensure maximum value of assets of Novo Banco, while minimizing the cost for taxpayer (EC 2014b).

The resolution plan by the BOP ensured that all general activities of BES continued without disruption (BOP 2014d). The resolution plan involved the transfer of assets, liabilities, off-balance sheet items, and assets under management from BES to Novo Banco. The sound or good assets of BES, including all deposits and senior debt, were transferred to Novo Banco to stabilize the operations of the bank for customers. The share capital from BES’s foreign subsidiaries and credit claims of the ES group were not transferred to Novo Banco, and remained in the bad bank to be wound down (EC 2014b). All off-balance sheet items, other than those related to BES Angola, ES Bank Miami, and Aman Bank in Libya, were transferred from BES to Novo Banco as per the resolution plan. Subordinated debt liabilities of EUR 0.9 billion and claims associated with the ES group were not transferred along with all other liabilities to Novo Banco (BOP 2014a). The goal of the resolution measure was to remove any uncertainties about the composition of Novo Banco’s balance sheet, to ensure a sale to private investors within 24 months (EC 2014b). See Figure 4 for an illustration of the BOP’s resolution procedures. Following are the steps in the resolution process based on the BOP’s valuations at the time (BOP 2014a):

- BES had assets of EUR 64 billion, which were written down by EUR 4.4 billion

- Assets worth EUR 59 billion are transferred to the bridge bank, Novo Banco

- BES had subordinated liabilities of EUR 0.9 billion, which were subject to burden sharing due to the provision of state funds, and were not transferred to Novo Banco

- The Resolution Fund provided EUR 4.9 billion of equity capital to Novo Banco

- BES’s bad bank was left with net assets of just EUR 1 billion to be liquidated, comprising EUR 4.4 billion of assets and EUR 902 million of subordinated liabilities (EC 2014b)

Figure 4: Balance Sheets of BES and Novo Banco According to Initial Valuations

Notes: BES’s annual report for 2014 presented updated adjustments to the transfer values for both Novo Banco and the bad bank, which are summarized in Figure 5. Novo Banco received EUR 57.6 billion of assets and had a negative equity position of EUR 0.9 billion before receiving the EUR 4.9 billion capital injection from the Resolution Fund. The legacy bad bank received only EUR 0.2 billion of assets after adjustments and had a negative equity position of EUR 2.4 billion after the resolution measures in 2014.

Notes: BES’s annual report for 2014 presented updated adjustments to the transfer values for both Novo Banco and the bad bank, which are summarized in Figure 5. Novo Banco received EUR 57.6 billion of assets and had a negative equity position of EUR 0.9 billion before receiving the EUR 4.9 billion capital injection from the Resolution Fund. The legacy bad bank received only EUR 0.2 billion of assets after adjustments and had a negative equity position of EUR 2.4 billion after the resolution measures in 2014.

Sources: BES 2015d; BOP 2014a.

Figure 5: Balance Sheets of BES (Legacy Bad Bank) and Novo Banco, after an Independent Valuation (EUR billions)

Source: BES 2015d.

Source: BES 2015d.

Treatment of Creditors and Equity Holders

1

All the equity holders, subordinated debt holders, and ES-linked liabilities of BES were to remain in the bad bank, which was to be wound down (EC 2014a). The liabilities that were excluded from transfer to Novo Banco, and remained in the bad bank, included all obligations and debt issued by ES group companies, and liabilities to shareholders with more than 2% shareholding in BES (BOP 2014a). This action was in line with burden sharing rules of the EC as per the 2013 Banking Communication (IP/13/672 and MEMO/13/886). The following is stated in Point 44 of the 2013 Banking Communication:

In cases where the bank no longer meets the minimum regulatory capital requirements, subordinated debt must be converted or written down, in principle before State aid is granted. State aid must not be granted before equity, hybrid capital and subordinated debt have fully contributed to offset any losses. (EC 2014b, 10)

The Portuguese Resolution Law extends burden-sharing requirements to non-contractual claims by related parties (such as deposits of shareholders with more than 2% holding) (EC 2014b). All depositor rights were to remain unchanged, and all deposits were transferred in full to Novo Banco (BOP 2014d). Similarly, all contractual credit obligations remained unchanged, and were transferred to Novo Banco (BOP 2014d).

The IMF noted that of the total losses shared, EUR 3.7 billion was borne by the equity holders and EUR 927 million by the subordinated debt holders of BES (IMF 2015). The EC noted that BES shareholders and subordinated debt holders contributed EUR 7 billion to the cost of the resolution as of 2017 (EC 2017a).

Novo Banco attempted to raise Tier-2 capital in 2018 for the first time since the resolution at a minimum yield of 8.5%, which was 200 to 300 basis points higher than that for peers at the time. This attempted capital raise by Novo Banco also comprised a controversial clause, which allowed the bank to change the underlying governing law for the bonds without prior approval from the issuer (Smith 2018).

Treatment of Clients

1

The resolution measure proposed for BES wanted to ensure the continuation of all operational activities of the bank to its clients (depositors, retail customers, and institutional investors) (EC 2014b). The board of the BOP also met to deliberate over the commercial treatment of retail clients of the bank, as per article 103 (1)(a), and implemented their decisions following article 27 (3) and 27 (4) of the Administrative Procedures Code. The retail customers holding unsubordinated debt of BES were to be repaid in full at maturity by Novo Banco. The retail customers that held unsubordinated bonds in special purpose entities or preference shares of BES were to not be purchased by Novo Banco. The board of Novo Banco was to reach a decision on the compensation provided to retail customers that were subscribed to bonds issued by the ES group (BOP 2014c).

Treatment of Assets

1

As seen in Figure 4, the resolution plan for BES included the creation of a bridge bank and the winding down of the legacy bad bank. Novo Banco, or the bridge bank, was to be sold to private investors within 24 months of its creation. The assets were expected to be wound down if not sold within the specified time frame (EC 2014b).

All assets of BES were transferred to Novo Banco, except the shares representing the share capital of BES’s foreign subsidiaries (Angola, Libya, United States), and credit claims on ES group international. The assets of BES were written down by EUR 4.4 billion to EUR 59 billion prior to transfer to Novo Banco (see Figure 4). Novo Banco was expected to be sold to private investors, through a competitive bidding process (BOP 2014a; EC 2014b).

Treatment of Board and Management

1

In July 2014, Ricardo Salgado, the head of BES for 23 years, was held in custody hearings in relation to several alleged crimes, including tax evasion and money laundering (BBC 2014a). BOP governor Carlos da Silva Costa stated in a speech on August 3, 2014, that the BOP was conducting a forensic audit to determine if any illicit acts were committed by the management and board of BES (Costa 2014a).

The results declared by BES in late July 2014 were found to reflect seriously poor management practices, including non-compliance with a BOP directive to not increase further exposure to the ES group (EC 2014b). The BOP also alleged potential illegal activities of EUR 1.5 billion, as identified by the external auditor of BES in July 2014 (EC 2014b). Novo Banco was governed by a board of directors and a board of auditors as appointed by the BOP (BOP 2014a).

In July 2015, Ricardo Salgado was placed under house arrest on suspicion of forgery, breach of trust, tax evasion, and money laundering (Agence France Presse 2015). Salgado has been the subject of administrative sanctions through cases launched by the BOP and CMVM, amidst several criminal proceedings (ECO News 2018). In 2023, Portugal’s Competition Court consolidated all of the fines imposed on Salgado to EUR 8 million, and the Supreme Court lowered the his prison sentence from eight to six years (Fernandes 2023b; Graeme 2023).

Cross-Border Cooperation

1

BES had a network of international branches across Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, Ireland, Macao, Poland, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. All of the bank subsidiaries owned by ESFG were located outside the EU in Dubai, Panama, and Switzerland (EC 2014b).

BES had a 55% stake in Angola’s second largest bank, BES Angola (BESA), and an additional EUR 3 billion loan to the Angolan entity (Coppola 2014). In 2014, BES was able to attribute losses of EUR 198 million to its subsidiary in Angola due to loan deterioration and application of certain provisions of the Angolan Industrial Tax Code. The National Bank of Angola had requested BES Angola to provide a capital injection to the subsidiary, with a total exposure of EUR 3.9 billion to the region (EC 2014b). After the BOP’s resolution plan was announced, the Angolan central bank (BNA) placed BESA into administration and revoked the sovereign guarantee to the bank. This led to an immediate loss of EUR 3 billion for the legacy bad bank, since BESA’s equity was wiped out and the inter-bank loan impaired. The Angolan central bank injected EUR 5 billion into BESA and appointed advisers to restructure the bank’s domestic loan book (Coppola 2014).

In December 2015, the BOP transferred EUR 2 billion of senior bonds from Novo Banco to the bad bank to be liquidated. Novo Banco had outstanding senior unsecured debt of EUR 5.4 billion at the time, which created uncertainty among investors about the different treatment of creditors in the same hierarchy of claims. Some analysts claim that the senior bonds that were transferred were governed by Portuguese law, and hence the decision could not be challenged in international courts (Reis and Almeida 2015). Fourteen asset managers sued to recoup their bond investments in Novo Banco citing discrimination and pointing out that Portuguese retail investors that held similar bonds did not bear losses (Hale and Arnold 2016). This move by the BOP was also seen by journalists as a break in the pari passu clause, which created a difference in treatment between bonds governed by Portuguese law and those by foreign law (The FT View 2016).

Other Conditions

1

The Portuguese regulators made a series of commitments to the EC with regards to the commercial operations, risk management, and duration of the resolution.

The resolved entities were banned from making any acquisitions during the course of its recovery, banned from coupon or dividend payments, and were to refrain from advertising any state financial support. Novo Banco was to also discontinue using the “BES” brand within two months of the resolution plan. BES’s bad bank was left with net assets of EUR 1 billion and had to commit to a balance sheet reduction plan. Novo Banco was also restricted from providing additional capital to its foreign subsidiaries from an amount larger than 5% of the Risk Weighted Assets (RWA) of the subsidiary or EUR 45–60 million. Novo Banco could not be sold to any previous shareholder of BES (greater than 2% holding). Novo Banco had to commit to the formation of a risk management department, which was responsible for monitoring credit risks, identifying early signals for loan impairment, and assessing overall exposures to an individual entity (EC 2014b).

Novo Banco was restricted to investing in investment grade or euro area sovereign securities. Novo Banco was not allowed to lend any loan amounts higher than the average ticket size loan from the past two years (EC 2014b).

Novo Banco was to have a strict executive remuneration policy, including incentives for the executives to sell the assets as soon as possible. The total compensation of any employee (wage, pension, bonus) could not exceed 15 times the average salary of employees at Novo Banco in the first year, and not exceed 10 times in the second year (EC 2014b).

Duration

1

Novo Banco was to be sold within 24 months since the announcement of the resolution plan, after which the banking license would be revoked and all unsold assets were to be wound down (EC 2014b).

In December 2014, Novo Banco sold BES’s former investment banking arm to Haitong Securities for EUR 379 million (Bray 2014). In the same month, three Iberian banks—Banco Popular, Banco Santander, and Banco BPI—were reported as lead bidders, with 17 expressions of interest submitted for Novo Banco (Wise 2014). In September 2015, the BOP suspended the sale process since it did not find the bids for Novo Banco satisfactory (EC 2015).

Toward the end of 2015, the BOP reported missing the deadline for the sale of Novo Banco after talks with the leading bidder failed; the bridge bank continued to report losses related to asset impairments (Minder 2015). The ECB’s stress tests highlighted a EUR 1.4 billion capital shortfall at Novo Banco, and the BOP liquidated EUR 2 billion in senior bonds by transferring them from Novo Banco to the bad bank (ECB 2015; Reis and Almeida 2015). The BOP’s decisions to selectively write down senior bonds led to lawsuits from investors, and controversy in the financial media (Hale and Arnold 2016). On December 9, 2015, the BOP amended a draft restructuring plan to the ECB, which presented a resolution strategy to turn BES into a profitable bank by 2020. The BOP committed to raising further capital from private sources (EC 2015).

In March 2017, the BOP and Resolution Fund sold 75% of Novo Banco to Lone Star, thereby securing a capital injection of EUR 1 billion into the bank and completing the role of the bridge bank before the August 2017 sale deadline. The deal between Lone Star and the Resolution Fund also included a “liability management exercise,” which would impose losses on senior unsecured bondholders; this was expected to provide at least EUR 500 million of additional CET1 capital but was later declared unsuccessful in October 2017. The Resolution Fund would continue to hold 25% in Novo Banco (EC 2017b).

The Lone Star deal involved a commitment by the Resolution Fund to inject up to EUR 3.9 billion of capital into Novo Banco if capital ratios fell below a specific level, as part of a CCA. The Portuguese state also committed to the EC that it would provide an additional capital backstop, separate from the CCA, in the event the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) indicated a capital shortfall, as long as capital could not be raised by Novo Banco independently in nine months, from Lone Star, or from the market. If further taxpayer funds were provided, Novo Banco would have to commit to reducing its full-time employees and branch count in a new restructuring plan (EC 2017b).

The CCA noted that potential bidders for Novo Banco had expressed concerns about the legacy business of BES. In 2019, the assets of Novo Banco were further separated into core and non-core, with non-core assets to be sold down, to ensure continuity of the bank’s focus on the domestic Portuguese market. The CCA also presented a revised risk management structure for Novo Banco, which includes interaction between the bank’s appointed board of directors, the Resolution Fund, the auditor (Ernst & Young), and the verification agent (Oliver Wyman) (see Figure 9 in the Appendix) (Resolution Fund 2019).

Novo Banco continued to report losses between 2018 and 2021, which led to multiple capital injections of total EUR 3.4 billion from the Resolution Fund into Novo Banco (see Figure 3). As part of 2021 budget deliberations, Portuguese politicians rejected a capital injection of EUR 476 million into Novo Banco (Goncalves 2020). Fitch Ratings reported that this decision, including a Parliamentary request for the Court of Auditors to review Novo Banco’s losses since 2018, could result in heightened political and legal uncertainty. Portugal’s prime minister and finance minister had to make public statements to reaffirm the state’s continued adherence to the CCA and willingness to provide additional resolution capital to Novo Banco. Novo Banco’s management and the Resolution Fund also strongly rejected claims that NPL sales were structured to provide an advantage to Lone Star, Fitch Ratings noted that increased uncertainty would weaken investor sentiment towards Portuguese banks, increase funding costs, and lead to further profitability pressures on the sector (Fitch Ratings 2021).

In the second half of 2021, the Resolution Fund provided a total of EUR 429 million in two separate capital injections to Novo Banco, to help restore capital ratios at the bank. The capital injections in 2021 by the Resolution Fund were financed by a syndicate of seven Portuguese banks, which lent EUR 475 million to the Fund (Goncalves 2021a).

For the full year 2021, Novo Banco reported a growth in its deposit base to EUR 27.3 billion, representing a 7% increase since 2016 (see Figure 10). Novo Banco also reported its first full year of profit of EUR 185 million, achieving a EUR 1.1 billion growth in net income since 2016. Novo Banco’s capital and liquidity position had also improved, with a CET1 ratio of 12.7%, liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) of 193%, and net stable funding ratio (NSFR) of 108% (Novo Banco 2022).