Broad-Based Emergency Liquidity

Norway: Covered Bond Swap Program

Purpose

“To facilitate banks’ access to long-term funding, Norges Bank assisted in establishing a swap arrangement in autumn 2008, where banks were permitted to borrow government securities in return for covered bonds” (Norges Bank 2010a)

Key Terms

-

Launch DatesOctober 12, 2008 (Announcement); November 14, 2008 (Operational)

-

Expiration DateOctober 19, 2009

-

Legal AuthoritySt.prp. nr. 5 (2008-2009)

-

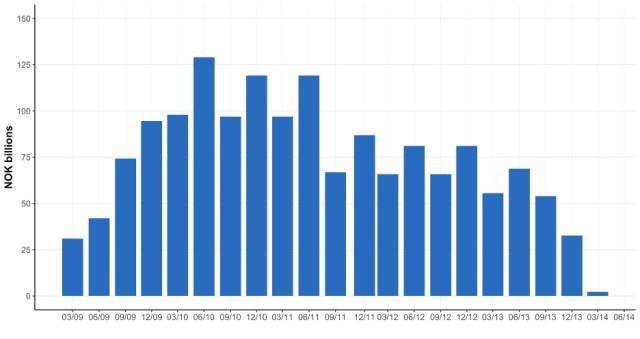

Peak OutstandingNOK 350 billion authorized and NOK 230 billion utilized

-

ParticipantsNorwegian commercial and savings banks eligible for open-market-operations; later included mortgage companies

-

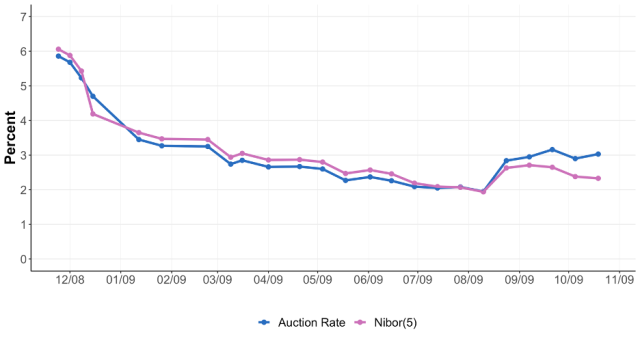

RateUniform

-

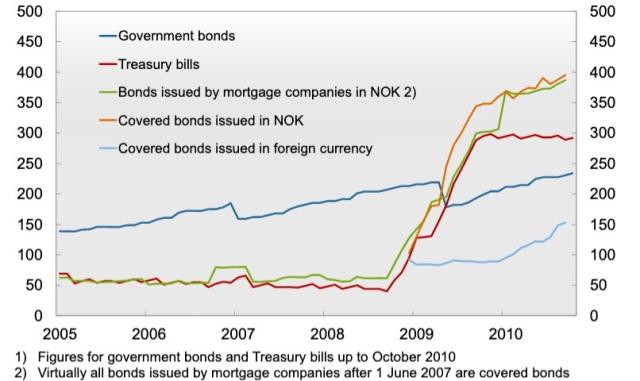

CollateralCovered bonds (OMFs)

-

Loan DurationInitially ranged from 3 months to three years, expanded to five years

-

Notable FeaturesMandatory rollover of treasury bills

-

OutcomesImproved liquidity and widespread usage of OMFs for funding

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

Part of a Package

Management

Administration

Eligible Participants

Funding Source

Program Size

Individual Participation Limits

Rate Charged

Eligible Collateral or Assets

Loan Duration

Other Conditions

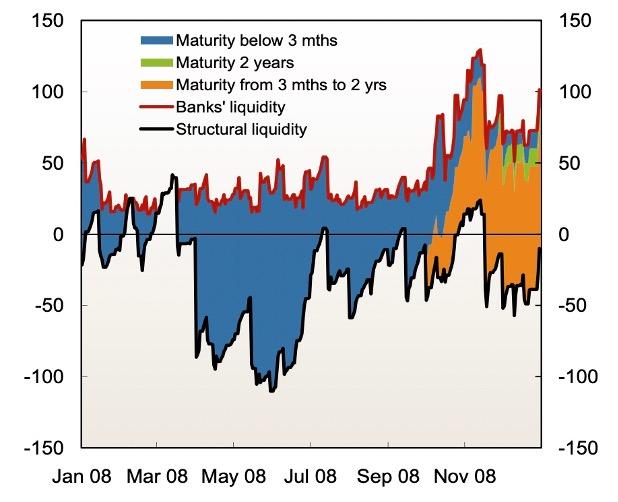

Impact on Monetary Policy Transmission

Other Options

Similar Programs in Other Countries

Communication

Disclosure

Stigma Strategy

Exit Strategy

Key Program Documents

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Broad-Based Emergency Liquidity

Countries and Regions:

- Norway

Crises:

- Global Financial Crisis