Resolution and Restructuring in Europe: Pre- and Post-BRRD

Latvia: Parex Bank Restructuring, 2008

Purpose

Latvian authorities sought to stabilize Parex in the most efficient way, determining it needed control of the bank to make sure the aid would be properly used and recovered. The LPA split Parex into good and bad banks to preserve its core activities and reduce its balance sheet to sell the bank to private owners

Key Terms

-

Size and Nature of InstitutionSecond-largest bank in Latvia, comprising 13.8% of the total assets in the Latvian banking sector

-

Source of FailureCapital shortfall owing to massive credit losses and market losses; deposit runs in autumn 2008

-

Start DateNovember 10, 2008: government took a 51% stake in Parex

-

End DateApril 20, 2015: Citadele sale transaction closed; liquidation of Reverta is ongoing

-

Approach to Resolution and RestructuringCitadele, a newly established “good bank,” took over all core assets and some noncore assets; Reverta, a “bad bank,” kept the remaining noncore and nonperforming assets

-

OutcomesEUR 767.5 million in losses as of December 2022

-

Notable FeaturesNotable Features Divergent treatment for majority and minority shareholders; EBRD participation in the good and bad banks

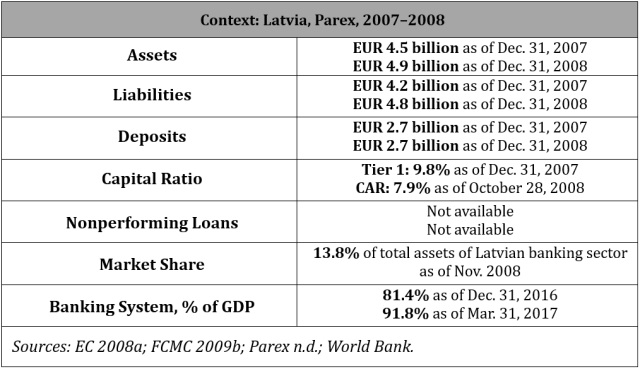

Heading into the Global Financial Crisis, JSC Parex banka was Latvia's second-largest bank in terms of assets, comprising 13.8% of total assets in the Latvian banking sector. In autumn 2008, Parex faced a capital shortfall due to massive credit and market losses in addition to increasing liquidity problems and deposits runs of 240 millions Latvian lats (USD 428.6 million). Parex had two senior syndicated loans maturing in February and June 2009, totaling EUR 775 million (USD 992 million), or nearly one-sixth of the bank's total liabilities. Latvian authorities doubted that Parex would be able to pay back, extend, or replace these loans. Authorities intervened at the beginning of November 2008 to provide emergency liquidity, take over the management, and inject capital. The two majority shareholders, who owned 85% of the bank, were effectively wiped out, while the minority shareholders and subordinated debtholders ultimately received nothing for their investments. In August 2010, the Latvian Privatization Agency split Parex into a new good bank and a remaining bad bank; the minority shareholders remained with the bad bank. The good bank, AS Citadele banka, was sold for EUR 74.7 million to Ripplewood Advisors LLC and a group of 12 international investors in April 2015. As of the writing of this case, the bad bank, AS Reverta, is still in liquidation. Latvia’s support for Parex peaked at EUR 1.7 billion. The state had lost EUR 428.8 million in share capital and EUR 339.7 million in liquidity support for a total loss of EUR 767.5 million as of December 2022.

This module describes the restructuring of JSC Parex banka. Parex also received emergency liquidity and capital injections (Decker forthcoming-a; Decker forthcoming-b).

Heading into the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 (GFC), Parex was Latvia’s second-largest bank in terms of assets, comprising 13.8% of total assets in the Latvian banking sector. Parex was especially vulnerable to contagion from overseas markets, as 40% to 50% of deposits were nonresidents’, a situation that the European Commission (EC) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) characterized as fragile (Bojāre and Romānova 2017; EC 2008a; OECD 2016). Parex’s loan portfolio was mostly to residents (Bojāre and Romānova 2017; EC 2008a; OECD 2016). In autumn 2008, Parex faced a capital shortfall due to massive credit losses and market losses in addition to increasing liquidity problems and deposit runs of 240 million Latvian lats (LVL; USD 428.6 million)FPer Bloomberg, USD 1 = LVL 0.56 on November 7, 2008. (EC 2008a; FCMC 2009a; FCMC 2009b; OECD 2016). Parex’s liquidity indicatorFThe Financial and Capital Market Commission set regulations for liquidity requirements. Parex had to hold at least 30% of the total amount of its current liabilities as liquid assets; current liabilities were defined as liabilities on demand and whose remaining term did not exceed 30 days (FCMC 2005; Parliament of Latvia 2008a, art. 37[2]). fell from 44.2% on August 31, 2008, to 31.4% on November 4, 2008; the regulatory minimum was 30%. Parex’s capital adequacy ratio (CAR) fell below the regulatory minimum of 8% on October 28, 2008 (EC 2008a; FCMC 2009b). The Financial and Capital Market Commission (FCMC) in Latvia then prohibited Parex from issuing new loans and acquiring new financial instruments (FCMC 2009b). The FCMC also required the bank to immediately increase its equity capital; Parex’s shareholders responded by investing LVL 3 million in subordinated capital (FCMC 2009b).

However, the previous measures were insufficient to address the bank’s problems. Parex had two senior syndicated loans maturing in February and June 2009, totaling EUR 775 million (USD 992 million),FPer FRED, EUR 1.00 = USD 1.28 on November 7, 2008. or nearly one-sixth of the bank’s total liabilities. According to the EC, Latvian authorities doubted that Parex would be able to pay back, extend, or replace these loans. For this reason, Latvian authorities decided to take a 51% stake in Parex and provide further public support measures (EC 2008a; Epstein and Rhodes 2019). According to the FCMC’s 2008 annual report, authorities did not want to give State Aid to Parex with the majority shareholders—Valērijs Kargins and Viktors Krasovickis (the two majority shareholders) in control; the two majority shareholders owned 85% of Parex (FCMC 2009b). Latvian authorities observed the experience of other countries and concluded that state aid would be properly used and recovered only if the government owned Parex (FCMC 2009b).

Starting in early November 2008, Latvian authorities performed three major interventions to stabilize Parex and the wider Latvian financial sector. First, on November 10, the government took over the bank and replaced management by paying a token amount of LVL 2.00 for a 51% stake from the two majority shareholders; weeks later, the government increased its participation to 85% and completely wiped out the two majority shareholders (EC 2008a; EC 2009a; FCMC 2009b). This allowed the government to later split Parex into bad and good banks (EC 2010). The government initially acquired Parex through the Latvian Mortgage and Land Bank (LHZB), a commercial bank used to develop Latvia’s mortgage lending system and mortgage-backed securities (Baltic Legal n.d.; EC 2008a; LHZB 2010). The government later transferred Parex’s shares to the Latvian Privatization Agency (LPA) for recapitalization and its potential sale because the LPA had experience in selling state-owned bank shares (FCMC 2009a; LPA 2009; Parex 2009b; Parex 2009d). Second, the Latvian Treasury deposited Treasury securities with Parex (state term deposits) that Parex could use as collateral to borrow cash from the central bank, the Bank of Latvia (BoL) (BoL 2008b; EC 2008a; EC 2010; IMF 2009; Parex 2011). Draws on the facility peaked at LVL 676.4 million at the end of 2008 (Parex 2010a). Third, from 2009–2010, the LPA recapitalized Parex to maintain an 11% CAR (EC 2009b; Parex 2011).

Other measures included a partial freeze on depositors, which the government prolonged in some form until January 2012 (FCMC 2008; IMF 2013; Parex 2011). Latvia also signed a Standby Arrangement (SBA) with the IMF and received broad-based support from the European Union (EU) and other European countries, which was conditioned on a full government takeover and subsequent restructuring of Parex (see Key Design Decision No. 2, Part of a Package) (FCMC 2008; FCMC 2009b; IMF 2009; IMF 2013; Reuters 2008).

Over the course of 2009 and 2010, the LPA injected into Parex a total of LVL 313.6 millionFThis figure may be inconsistent due to lack of clarity about recapitalizations as capital injections or as conversions from liquidity support (Decker forthcoming-a). in Tier 1 capital and LVL 50.3 million in Tier 2 capital (Citadele 2011; EC 2009b; EC 2010; Parex 2011; Parex 2012). Recapitalization was also achieved by converting LVL 152.5 million of state term deposits from the Ministry of Finance into bank capital (EC 2010; Parex 2010a; Treasury 2011). The Latvian government also invited the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) to become a shareholder in Parex to reassure stakeholders, given the EBRD’s reputation and experience in bank restructuring (Parliament of Latvia 2015). The EBRD injected capital in September 2009 and July 2010 and later sold part of its stake (see Key Design Decision No. 15, Duration) (Citadele 2011; EBRD 2009; Parex 2009i; Reverta 2017).

On August 1, 2010, the LPA split Parex into a new good bank, AS Citadele banka, and a remaining bad bank, AS Reverta (Reverta)FThe bad bank initially kept the name Parex after the split on August 1, 2010, but changed its name to Reverta in May 2012 (EC 2014a; OECD 2016). For clarity, this case study refers to the post-split bad bank as Reverta. (EC 2014a; Parex 2011). Citadele would focus on three core business segments in the Baltics: corporate, retail, and wealth management. Reverta would keep the remaining noncore and nonperforming assets. Reverta’s goal was to maximize the recovery of state aid in liquidation (EC 2010; Parex 2011).

Capital and liquidity support was also restructured with the split. Citadele took LVL 50.3 million of Tier 2 capital, and Reverta took the equity capital injected on March 29, 2009. At the time of the split, 16 term deposits were in effect for EUR 635 million (LVL 446 million). Eight of those deposits went to Citadele, four of which worth LVL 12 million were already terminated. Citadele’s remaining four term deposits were converted into equity for a recapitalization of LVL 103 million (EC 2010; Treasury 2011). Reverta took the other eight term deposits, of which LVL 49.5 million was ultimately converted to bank capital (EC 2010; EC 2014b). In December 2011, all of Reverta’s outstanding term deposits were converted to debt securities (Parex 2012; Reverta 2013). These debt securities remained with Reverta when the bad bank later went into liquidation in 2017 (Reverta 2018).

On April 20, 2015, the LPA closed the sale transaction of 75% of Citadele to Ripplewood Advisors LLC, a US private equity firm, and a group of 12 international co-investors for EUR 74.7 million (Citadele 2015b). The EBRD maintained a 25% stake (Citadele 2011).

Including capital and liquidity support, Latvia’s support for Parex peaked at EUR 1.7 billion. As of April 2015, unrecovered state aid totaled EUR 784 million: EUR 35.0 million in Citadele’s subordinated capital (4.5% of total unrecovered state aid), EUR 294.0 million in Reverta’s share capital (37.5% of total unrecovered state aid), and EUR 455.0 million in bonds in Reverta converted from liquidity support (58.0% of total unrecovered state aid) (Parliament of Latvia 2015).

Citadele repaid the last term deposit of state aid in February 2015, 10 months ahead of schedule (Citadele 2013b; Treasury 2013). In total, Citadele repaid the full amount of term deposits it owed since the split, EUR 203.7 million, and EUR 14.7 million in interest—interest accruing since the split of the bank in August 2010 until March 2012. Citadele also repaid the Treasury an additional LVL 3.5 million as “additional compensation for the use of state aid in line with the commitments given to the EC” (Citadele 2013b, 3).

On January 4, 2017, Citadele repaid its subordinated loan from the LPA, thereby settling its remaining obligations to the Latvian government (Reverta 2018).

The EBRD ended its participation in Reverta on March 7, 2017 (Reverta 2017). The liquidation of Reverta began on July 6, 2017 (Reverta 2018). On November 17, 2017, the LPA created a new subsidiary and limited liability company, REAP, for the sole purpose of managing Reverta’s assets and claim rights. By the end of 2017, Reverta had EUR 365.3 million in outstanding liquidity support, and the LPA wrote off its entire investment in Reverta share capital (LPA 2019; Reverta 2018). REAP sold most of the real estate assets taken over by Reverta during the course of 2018 (LPA 2019). As of the writing of this case, Reverta is still in liquidation, with a total asset value of EUR 1.7 million as of December 31, 2022 (LPA 2023; Reverta 2023).

According to a parliamentary report published in December 2015, the state estimated EUR 500 million to EUR 600 million in losses (Parliament of Latvia 2015). According to Reverta’s annual report, the state had lost EUR 428.8 million in share capital and EUR 339.7 million in liquidity support for a total loss of EUR 767.5 million as of December 2022 (Reverta 2023).

See Figure 1 for a timeline of major events in the restructuring of Parex.

Figure 1: Timeline of Major Events in the Restructuring of Parex

Source: Author’s analysis.

In its annual report for 2009, the State Audit Office of the Republic of Latvia (SAO) said that the takeover process was unclear and not transparent (SAO 2010).

In a 2012 book published by the IMF, Mark Griffiths characterizes the initial agreement to take a 51% stake in Parex in November 2008 as “half-hearted” and “insufficient,” noting that runs continued and the FCMC still had to enact a partial freeze on depositor withdrawals to stabilize deposits and conserve liquidity (Griffiths 2012, 114).

In an article titled “Budgeting in Latvia” in the OECD Journal on Budgeting, the authors said that LHZB’s 51% stake in Parex was a “failed attempt to restore confidence by a partial takeover” (Kraan et al. 2009, 189).

In a staff report published in January 2009, the IMF said that the initial intervention—comprising the 51% government stake—was a misstep and “failed to stem the deposit run” (IMF 2009, 8). Left unresolved by their maturity dates in February and June 2009, Parex’s senior syndicated loans could lead to significant capital outflows of EUR 1.0 billion from Latvia, according to the IMF. The IMF said that the subsequent intervention—comprising the government’s 85% stake and installation of new management at Parex—more credibly moved toward stabilization. Additionally, the IMF calls for a clear exit strategy that minimized the state’s losses (IMF 2009).

In a September 2010 decision, the EC remarked “positively” on the asset-separation strategy, in which a new good bank took Parex’s core and performing assets and a remaining bad bank kept Parex’s nonperforming assets. The EC said this strategy “[limited] to some degree the necessity for a fully-fledged valuation of the extent of the impairments” (EC 2010, 27).

In “Transition Report 2010: Recovery and Reform,” the EBRD said that Latvian authorities “[had] made significant progress in restructuring Parex Banka” (EBRD 2010, 125). The EBRD also said that Latvian authorities’ intention to reprivatize Citadele would revive credit growth in the private sector (EBRD 2010).

In December 2015, the Parliament of Latvia published its final report on the sale process of Citadele. The report blames the Cabinet of Ministers for suboptimal choices, noting that the Cabinet rather than the LPA made high-level decisions about the sale process. On the process decisions taken by the LPA, the report says that authorities did not seek an independent price valuation of Citadele before its sale. The report also criticizes the opacity and slowness of Citadele’s sale to Ripplewood and associated investors. Furthermore, the decision to continue negotiations with only Ripplewood and associated investors forsook a higher sale price because Ripplewood offered the lowest share price among the three selected bidders (Parliament of Latvia 2015).

In 2016, the SAO published conclusions of its regulatory audit of Citadele’s sale process. The SAO says that when takeovers and privatizations have a significant impact on the national economy and tens of millions of taxpayers’ money is involved, the government and parliament should create a legal framework with three basic principles. First, relevant authorities should be involved in decisions. The SAO notes that the decisions around Citadele’s sale process were based on recommendations of outside consultants rather than authorities such as the BoL. Second, there should be clearly delineated responsibilities among government bodies that take actions in a given intervention. Third, there should be independent supervision of interventions so that the state achieves the most favorable outcome for taxpayers (SAO 2017).

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

1

In autumn 2008, Parex faced a capital shortfall due to massive credit losses and market losses in addition to increasing liquidity problems and deposit runs of LVL 240 million (EC 2008a; FCMC 2009a; OECD 2016). Parex’s liquidity indicator fell from 44.2% on August 31, 2008, to 31.4% on November 5, 2008; the regulatory minimum was 30%. Parex’s CAR fell below the regulatory minimum of 8% on October 28, 2008 (EC 2008a; FCMC 2009b).

Parex had two senior syndicated loans maturing in February and June 2009, totaling EUR 775 million, or nearly one-sixth of the bank’s total liabilities. According to the EC, Latvian authorities doubted that Parex would be able to pay back, extend, or replace the two senior syndicated loans maturing in February and June 2009. These senior creditors were preparing to announce default in mid-November 2008, meaning the EUR 775 million would have been due immediately. Considering these senior syndicated loans, deposits runs, insufficient bank capital, and a request from Parex’s management for help, Latvian authorities decided to intervene (EC 2008a; Epstein and Rhodes 2019).

Initial Investment Agreement

The November 10 takeover of a bank by LHZB was unprecedented in the Latvian financial sector since privatization in the 1990s (FCMC 2009a; FCMC 2009b). In its annual report for 2008, the FCMC said:

By taking over [Parex] the Latvian state prevented insolvency of a leading Latvian credit institution, stabilized the whole Latvian financial system and certified to the depositors that the state [was] ready to support them. The loss to the financial system as a result of the collapse of a bank like [Parex] would have exceeded the funds invested to stabilize the operations of [Parex] because customers—residents, non-residents, natural persons and legal entities—would have no longer believed in Latvian banks and consequently undermined their activity. (FCMC 2009b, 10)

The FCMC also said that a negotiated government takeover of Parex was the most efficient way to stabilize the bank.FAccording to a parliamentary report, taxpayers would have paid EUR 939.1 million to fulfill deposit guarantee commitments had the government not taken over Parex (Parliament of Latvia 2015). Although it was possible to take the bank’s shares without shareholders’ consent under Article 105 of the Latvian Constitution, complex legal proceedings would have slowed the process, and state aid would have been too late. Thus, Latvian authorities decided to negotiate the takeover with the two majority shareholders (see Key Design Decision No. 9, Treatment of Creditors and Equity Holders) (FCMC 2009a; FCMC 2009b).

These negotiations were held among the FCMC, Ministry of Finance, BoL, and Parex. The Cabinet of Ministers made the decision to take a 51% stake in Parex on November 8, 2008 (FCMC 2009b). The two majority shareholders said that it was the correct decision to seek help from Latvian authorities, and authorities subsequently decided the structure of assistance. The majority shareholders also told the press that they had the right of first purchase when the government decided to sell its 51% stake (BBC 2008a). If the two majority shareholders did not meet all the conditions in the initial investment agreement within two weeks, LHZB and the Latvian government could terminate the agreement (FCMC 2009a).

According to the FCMC’s 2008 annual report, authorities did not want to give state aid to Parex with the two majority shareholders in control. Latvian authorities observed the experience of other countries and concluded that state aid would be properly used and recovered if the government owned Parex (FCMC 2009b).

Amended Investment Agreement

According to the IMF, Latvian authorities thought that the initial intervention would convince nonresidents to keep their deposits at Parex. However, deposit outflows continued (IMF 2009).

After November 10, the two majority shareholders did not receive the consent of two-thirds of the senior syndicated lenders to fulfill the conditions set forth in the initial investment agreement. However, the senior syndicated lenders indicated that they would agree to refinance the loans if LHZB acquired all of the shares owned by Kargins and Krasovickis. According to the FCMC, the IMF, the EC, and Sweden’s central bank also insisted that Latvian authorities take all the shares owned by Kargins and Krasovickis and remove the two from management. This prompted Latvian authorities to amend the investment agreement (FCMC 2009a).

On December 3, 2008, the Cabinet of Ministers decided to amend the investment agreement to acquire all remaining shares held by the two majority shareholders, bringing the government’s total stake to 85%, to make sure that state aid would be properly utilized and recovered (EC 2008a; FCMC 2009b). The amended agreement did not change the total purchase price of LVL 2.00 (FCMC 2009b). However, the amended agreement removed Kargins and Krasovickis from the board, and they no longer had the right of first purchase of the government-owned Parex shares (EC 2009a; Reuters 2008).

Part of a Package

1

Broad-Based Liquidity Measures

From the end of August until the end of November 2008, the BoL sold EUR 900 million in foreign currency to defend the peg of the lat to the euro, due to concerns about liquidity and access to outside private capital markets.FIn 2008, Latvia was a member of the European Union but had not yet adopted the euro as its currency. During this time, the BoL’s official foreign reserves fell by 20% to EUR 3.4 billion, one-third of short-term external debt but more than 100% of base money (BoL 2009; IMF 2009). Nonresident deposit runs on Parex played a large role in system-wide outflows. According to the IMF, any change in the nominal exchange rate would have immediately diminished private sector net worth in Latvia because the majority of deposits and loans were foreign currency denominated (IMF 2009).

On October 24, 2008, the BoL lowered reserve requirements, thereby releasing LVL 200 million in liquidity to the banking system (BoL 2008a; IMF 2009). The BoL lowered the reserve ratio for bank liabilities with two-year maturities from 6% to 5% and for other liabilities from 8% to 7% (BoL 2008a; BoL 2009). The BoL further lowered reserve requirements in November and December 2008, which released an additional LVL 380 million (IMF 2009).

In a January 2009 report, the IMF says that the BoL provided LVL 555 million (3.5% of GDP) in liquidity to the entire banking system to meet deposit runs. Of the total LVL 555 million, LVL 195 million was for operations backed by domestic Treasury bills specifically issued for liquidity support to Parex (IMF 2009). We interpret the IMF and BoL documentation to mean that the BoL released a total of LVL 1.1 billion in liquidity from August 2008 to January 2009.

Support from the IMF, EU, and Other European Countries

From November 17–23 and December 5–18, 2008, senior government officials (including opposition party leaders), social partners, and representatives of financial institutions met with the IMF to discuss an SBA that would include IMF aid of approximately one-third of Latvia’s GDP (EIU 2008; IMF 2009). According to Reuters and the FCMC, the IMF said that it would grant support if the Latvian government took full control of Parex (FCMC 2009b; Reuters 2008). On December 23, 2008, the IMF announced a 27-month Standby Arrangement for 1.5 billion special drawing rights (SDR; EUR 1.7 billion) under its Emergency Financing Mechanism (EFM). Additional support came from multilateral organizations and other European countries (see Key Design Decision No. 13, Cross-border Cooperation) (IMF 2009). In the interim between the announcement and when the loans took effect, Latvia used already-established short-term swap facilities up to EUR 500 million with the central banks of Denmark and Sweden (EIU 2008). The SBA was extended to 36 months at the time of the second review (IMF 2013).

Per the structural performance criteria and benchmarks under the SBA, Parex’s management had to submit a restructuring plan to the FCMC and EC (IMF 2013). The SBA also called for broader financial sector reform—including emergency legislation allowing bank takeovers, a targeted examination of the banking system, commitments from foreign banks to maintain their presence in Latvia, and improved supervision and intervention capacity of the BoL. On private debt restructuring, the SBA called for legislative and judicial reforms that would expedite restructuring processes (IMF 2009).

Emergency Liquidity, Partial Freeze, Capital Injections

Latvian authorities said that Parex would receive a maximum amount of liquidity support capped at LVL 1.5 billion (EC 2009a). On November 11, 2008, the Ministry of Finance instructed the Treasury to make an initial term deposit of LVL 200 million in Parex so that the bank could acquire government debt securities to use as collateral to obtain cash reserves from the BoL (EC 2008a; FCMC 2009b). The deposit had a maturity of one year and an interest rate set at 20.3%. From 2008 to 2010, the Treasury provided additional term deposits. Interest rates varied depending on term, value of the floating element of the interest rate, and currency denomination (see Decker forthcoming-b) (EC 2008a).

On December 1, 2008, Latvian authorities granted Parex’s request for a partial freeze on withdrawals and transfers. The FCMC said that this measure was justified considering the run on deposits and other leveraged funds from Parex (FCMC 2008; FCMC 2009b). Individual withdrawals were capped at LVL 35,000 per month. Withdrawals were capped at LVL 35,000 per month for businesses with 10 or fewer employees. Withdrawals were capped at LVL 350,000 per month for businesses with 11–250 employees (AFP 2008; FCMC 2008; Tapinsh 2008). The partial freeze did not apply to businesses with more than 250 employees (AFP 2008; Tapinsh 2008). While the partial freeze was initially scheduled to end by mid-2009, authorities prolonged the partial freeze in some form until January 2012 (EC 2010; IMF 2013; Parex 2011). Reverta’s annual reports say that the bad bank began to repay LVL 9.9 million to depositors after the lifting of restrictions on January 2, 2012 (Parex 2012).

Per the State Aid measures approved by the EC, Latvian authorities started capital injections on May 22, 2009, to maintain a higher CAR of 11% during the rescue phase (see Decker forthcoming-a) (EC 2009b; Parex 2011).

Guarantees

On November 14, 2008, creditors of the senior syndicated loans, amounting to EUR 775.0 million, were preparing to announce a default event, which meant that these loans would have become due immediately rather than on their maturity dates in February 2009 and June 2009. Latvian authorities negotiated with these creditors to maintain the maturity dates in February and June, provided that the government issued a guarantee for these loans. The government also guaranteed new loans issued to refinance the syndicated loan maturing in February 2009. Latvian authorities told the EC that these guarantees would be cheaper than new borrowings, since the existing senior syndicated loan agreements had pre-crisis interest rates (EC 2008a).

The fee for the guarantees on these loans was calculated from: (a) the median value of the current five-year credit default swap spreads for the rating category BB, based on sample of banks chosen by the Treasury, (b) an add-on fee of 50 basis points (bps), and (c) a guarantee service fee of 10 bps to the Treasury (EC 2008a).

Beyond six months, Latvia had to obtain additional approval from the EC to guarantee loans as a part of Parex’s restructuring and resolution (EC 2008a).

On December 16, 2008, the FCMC increased the coverage limit of the already-existing deposit insurance scheme,FFor more on the guarantee scheme, see Vergara (2022). but this ultimately did not apply to Parex (EC 2008b; Parliament of Latvia 2011b). Latvian authorities nevertheless assert that all guaranteed deposits were paid out.FThe author received comments on this case from officials at the BOL.

In March 2010, Parex signed an agreement with the European Investment Bank (EIB) for a credit line up to EUR 100 million to finance small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The EIB required a government guarantee for the credit line as long as Citadele remained below investment grade (EC 2010; Treasury 2012). After the split, this credit line was transferred to Citadele (EC 2010).

Legal Authority

1

According to a parliamentary report released in June 2011, Latvia did not have appropriate legislation for its rescue of Parex at the time the government initially intervened (Parliament of Latvia 2011c).

Roles of LHZB and the LPA

LHZB was established on March 19, 1993, as a state-owned commercial bank based on a decree by the Cabinet of Ministers. Latvian authorities used LHZB to develop Latvia’s mortgage lending system and mortgage-backed securities (Baltic Legal n.d.; LHZB 2010). According to the EC’s decision on November 24, 2008, the Latvian state could tell LHZB to buy shares in other companies, Parex in this case (EC 2008a). On December 3, 2008, when LHZB acquired an 85% stake in Parex, the Cabinet of Ministers also issued decree No. 820. This decree set LHZB on the course of transformation from a commercial bank to a development bank, with a goal of gradually phasing out all commercial banking activities by the end of 2013 (LHZB 2010).FLatvia recapitalized LHZB between November 2009 and January 2012 by LVL 262.7 million (EC 2013). Authorities also provided a liquidity facility up to LVL 250.0 million, guarantees to international creditors of LHZB’s commercial segment up to LVL 32.0 million, and additional liquidity support up to LVL 60.0 million for the liquidation of a different bank, HipoNIA, under LHZB ownership (EC 2013). Latvia later restructured LHZB by dividing the bank’s assets and liabilities into various bundles sold to separate buyers by June 30, 2013 (EC 2013).

The Cabinet of Ministers established the LPA with Order No. 149-r on March 29, 1994 (Cabinet of Ministers 1997). The LPA’s founding purpose was to ensure the privatization of state properties according to the Law on Privatization of State and Local Government Property Objects (Cabinet of Ministers 1997).

On December 30, 2008, the Parliament of Latvia passed the Bank Takeover Law, which allowed the BoL or FCMC to initiate a bank takeover when the wider Latvian banking system was threatened (Parliament of Latvia 2008b). However, the law did not apply to the takeover of Parex since it was passed after the government’s intervention began (Parliament of Latvia 2008b, art 2[3]).

The Law on Budget and Financial Management, Section 36, Paragraph 6 allowed the finance minister to extend state loans, based on a decision by the Cabinet of Ministers (Parliament of Latvia 2009, sec. 36[6]). According to the Treasury’s annual reports, this was the legal basis for the loans provided from the Treasury to the LPA to fund Parex’s recapitalization (Treasury 2010; Treasury 2011).

EC Decision-Making

Latvian authorities placed behavioral constraints on Parex to avoid undue distortions of competition for EC compliance, which the EC noted in its decision on November 24, 2008 (see Key Design Decision No. 14, Other Conditions) (Competition Council 2008, para. 5.3; EC 2008a).

On November 24, 2008, the EC decided Latvia’s aid measures were compatible with the common market; the EC did not raise objections (see Figure 2). The EC evaluated Latvia’s intervention according to Article 87 of the European Commission Treaty (EC Treaty) (EC 2008a; EU 2002). The EC said that the partial nationalization of Parex did not constitute state aid to Parex’s shareholders, because the Latvian government paid a token LVL 2.00 and the EC was not aware of any obligations the existing shareholders had against the bank or its creditors of which they would have been relieved due to the transaction (EC 2008a).

On September 15, 2010, the EC found that the restructuring plan was compatible with Article 107(3)(b) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and properly addressed viability, burden sharing, and competition distortion (EC 2010).

On March 6, 2012, Latvian authorities sent a request to the EC to amend the restructuring plan. The EC allowed these changes on August 10, 2012 (see Key Design Decision No. 14, Other Conditions) (EC 2012).

On October 1, 2013, Latvian authorities requested another amendment to the State Aid authorization. Latvia wanted to postpone the deadline to divest Parex’s wealth management business per the September 2010 EC decision (see Key Design Decision No. 14, Other Conditions). In corresponding with Latvia, the EC discovered that Latvia took certain actions without notifying the EC: extending the maturity of some subordinated loans in presplit Parex and later Citadele in addition to exceeding the maximum authorization of liquidity support to Reverta. In July 2014, the EC issued a decision responding to these violations of State Aid. On the divestment of Citadele’s wealth management business, the EC recognized the difficulty in finding interested buyers given Latvia’s market conditions at the time. The EC noted Latvia’s proposal to sell Citadele’s wealth management business with the good bank itself to increase market interest and thus increase the likelihood of Citadele’s sale. On the maturity extensions, the EC acknowledged that Latvia’s changes better aligned subordinated debt amortization under Basel II rules and Latvia regulators’ changes to the CAR requirement during the rescue phase. On the breach of maximum liquidity support to Reverta, the EC noted that Reverta had a lower asset quality than expected in addition to slower than expected recovery of collateral and litigation with debtors. Moreover, Reverta’s loss of its banking license in 2012 meant that the bad bank did not need to convert further liquidity support into capital. Considering the difficulty in asset recovery and the unconverted liquidity support, the EC concluded that Reverta’s emergency liquidity was limited to the minimum necessary for its resolution (EC 2014b).

Figure 2: Timeline of EC Reviews for State Aid to Parex

Source: Author's analysis.

Source: Author's analysis.

Administration

1

On November 3, 2008, negotiations commenced among the FCMC, Ministry of Finance, BoL, and Parex (FCMC 2009b). On November 10, 2008, the two majority shareholders, Parex, and the Latvian government signed an investment agreement (EC 2008a).

Financial and Capital Market Commission

The Financial and Capital Market Commission supervised and issued regulations pertaining to the activities of banks, credit unions, insurance undertakings and insurance intermediaries, and private pension funds (FCMC 2009b). The FCMC also had to approve insolvent institutions’ restructuring plans (Parliament of Latvia 2008a).

The FCMC was managed by a board consisting of five members: a chairperson, a deputy, and three council members who were also directors of the FCMC’s departments (FCMC 2009b; Parliament of Latvia 2002). All council members were appointed by the parliament on the advice of the finance minister and BoL president. Council members served for terms of six years (Parliament of Latvia 2002). The council adopted decisions by a simple majority vote. In the event of a tie, the chairperson’s vote was decisive (Parliament of Latvia 2002).

Latvian Mortgage and Land Bank

From November 10, 2008, to February 27, 2009, Latvian Mortgage and Land Bank held the government’s shares in Parex (EC 2008a; Parex 2009d). When the Cabinet of Ministers decided to acquire the two majority shareholders’ 85% stake, the Cabinet required LHZB to divest itself of Parex within one year. Thus, LHZB had to seek sale advisors and interested buyers right away. LHZB selected the investment bank Nomura International plc. as lead advisor for the sale, and Nomura remained in that role after the LPA took over the government’s stake. LHZB’s role in the restructuring of Parex ended with the transfer of Parex shares to the LPA in February 2009 (FCMC 2009a).

Latvian Privatization Agency

On February 27, 2009, per the direction of the Cabinet of Ministers, LHZB transferred the government’s 85% stake in Parex to the LPA for further capital increases and the potential sale of the bank (LPA 2009; Parex 2009b; Parex 2009d). Thus, the LPA bought Parex’s shares from LHZB for LVL 2.00 and EUR 0.01. The FCMC said the Cabinet of Ministers made this decision because the LPA had experience selling state-owned bank shares, pointing to the examples of JSC Latvijas Krājbanka and JSC Latvijas Unibanka (FCMC 2009a).

The LPA board managed the agency’s day-to-day activities. The LPA board organized the privatization of state-owned property and approved regulations for the privatization of specific state-owned property after the LPA council issued an opinion (Cabinet of Ministers 1997). The LPA board met at least once per week and made decisions by a simple majority vote. In the case of a tie, the board chairperson’s vote was decisive (Cabinet of Ministers 1997).

LPA board members were appointed for a maximum period of three years, and they could be reappointed. At least half of the LPA board members had to be Latvian citizens; the remaining members had to be permanent residents of Latvia for at least 21 years. The chairperson of the LPA board was also the general director, approved by the Cabinet of Ministers upon the recommendation of the trustee. The general director managed the activities of the LPA board. Upon the recommendation of the general director, the LPA board approved the deputy general director (Cabinet of Ministers 1997).

The council of experts was a consultative body whose members evaluated specific privatization undertakings and presented these findings to the LPA board before the latter made a decision (Cabinet of Ministers 1997, art. 4[19]). Members of the council of experts were recommended by the LPA board and approved by the LPA council (Cabinet of Ministers 1997, art. 4[20]).

Reverta’s liquidation began on July 6, 2017. Later, on November 17, 2017, the LPA created a new subsidiary and limited liability company, REAP, for the sole purpose of managing Reverta’s assets and claim rights (see Key Design Decision No. 15, Duration) (LPA 2019; Reverta 2018).

Sell-Side Advisors

On March 3, 2009, Parex announced that the Latvian government appointed Nomura as a strategic, sell-side advisor (Parex 2009e). Nomura submitted a restructuring plan to the Cabinet of Ministers, which approved the plan on March 23, 2010 (Parex 2011).

In October 2013, the Cabinet of Ministers approved measures to hire Société Générale SA as a financial advisor and Linklaters LLP as a legal advisor in the LPA’s sale of Citadele (Citadele 2013a; OECD 2016). Advisory firms submitted applications to a special commission with representatives from the Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Economics, LPA, Citadele’s council, and the EBRD; the special commission selected the best firm (Citadele 2013a).

Governance

1

Latvian Privatization Agency

The LPA council governed the LPA’s activities (Cabinet of Ministers 1997, arts. 3[1], 3[20]). Five members comprised the LPA council, appointed by the Cabinet of Ministers on the recommendation of the trustee and each parliamentary faction (Cabinet of Ministers 1997, arts. 3[10-11]). LPA council members could serve a maximum of three years (Cabinet of Ministers 1997, art. 3[14]). At least two-thirds of the LPA council had to be Latvian citizens. If noncitizens served, they had to be permanent residents of Latvia for at least 21 years (Cabinet of Ministers 1997, art. 3[13]).

The LPA council had to issue an opinion on the privatization of a specific state-owned property before the LPA board could issue subsequent regulations. The LPA council received a report on the LPA’s activities from the board once per quarter (Cabinet of Ministers 1997). The trustee appointed sworn auditors to check the LPA’s activity and produce a report (Cabinet of Ministers 1997).

The Ministry of Economics owned 100% of the LPA’s shares, and the LPA board’s activities were ultimately subject to oversight by the Cabinet of Ministers (Cabinet of Ministers 1997; LPA 2009).

Restructuring Process

According to an EC decision on September 15, 2010, independent trustees would oversee the restructuring plan implementation and compliance with the behavioral restrictions imposed on Citadele and Parex by the Latvian government after the split (see Key Design Decision No. 14, Other Conditions). The trustees would prepare detailed, regular reports for the Latvian government to send to the EC. The trustees would be independent of Citadele, Reverta, and the Latvian government; the trustees would not have conflicts of interest. The EC had the discretion to approve or reject the proposed trustees. If the government did not sell Citadele by a certain deadline, a divestiture trustee would be appointed to carry out the sale (see Key Design Decision No. 15, Duration) (EC 2010).

Research has not revealed whether trustees were indeed appointed to oversee Citadele’s and Reverta’s compliance with behavioral constraints, but a divestiture trustee was presumably unnecessary given Citadele’s sale before the deadline.

Parliamentary Investigations

On February 24, 2011, the Parliament of Latvia launched an investigation commission on possible illegal activities in the process of taking over and restructuring Parex (Parliament of Latvia 2011a). The commission issued its report on June 9, 2011. The investigation commission stated that its report was not sufficiently exhaustive because Parliament did not vote to extend the length of the investigation. The commission said that it was not convinced that the government’s majority stake in Parex and other rescue funds in Parex’s resolution were safely and effectively used in the best interest of Latvian citizens (Parliament of Latvia 2011c).

On November 13, 2014, the Parliament of Latvia launched another investigation into the progress of Citadele’s sale process. The investigation considered the sale price, resale bank period, provisions contained in the share sale agreement, expense of sell-side advisors, and expense of public relations services. The Parliament released its final report on Citadele’s sale process in December 2015 (Parliament of Latvia 2015).

Communication

1

Initial Investment Agreement

In early November 2008, Prime Minister Ivars Godmanis spoke to the press and presented a binary choice: either take control of Parex or allow it to enter bankruptcy. He said that the government had to protect Parex due to its size and importance in the Latvian banking system as a whole. Godmanis said that he saw no need for action to support other banks at the time but did not rule out the possibility in the future (AP 2008; Lannin 2008a). The partial nationalization of Parex would allow the bank to continue its operations and retain depositors’ trust, according to the government (Lannin 2008a).

Then–BoL Governor Ilmars Rimsevics said, “This was an attempt by the Latvian authorities to step in earlier rather than later” (Anderson 2008a). Rimsevics also said that the sooner the LHZB returned Parex to the private sector, the better (Anderson 2008a). Latvian authorities said that Kargins and Krasovickis would not be excluded from the sale process once the liquidity crisis was over (Lannin 2008b).

The Ministry of Finance promised to publicly publish parts of the 77-page takeover agreement that did not contain confidential information (FCMC 2009b; Petrova 2008). Research has not uncovered any portion of the takeover agreement.

Amended Investment Agreement

On December 9, 2008, the Ministry of Finance published a press release in the Latvian Journal (Ministry of Finance 2008). The announcement contained information on Parex’s new board and management; Kargins and Krasovickis were removed. The press release also communicated the new shareholder structure: 85% owned by LHZB and 15% owned by minority shareholders. The finance minister said the government intervened because of deposit runs (Ministry of Finance 2008). In its financial statements for 2008, LHZB said that its takeover of Parex was short term and had “no substantial impact” on LHZB’s operations or risks (LHZB 2009).

Disclosure

In a document dated May 2009, the FCMC said authorities initially limited information by classifying documents as “secret” or “restricted use information” according to the State Secret and Information Disclosure Law (FCMC 2009a, 1). The FCMC said this was to protect the interests and legal rights of those receiving financial services (for example, depositors), the state, and business participants—while acknowledging that this choice led to a “variety of interpretations” surrounding Parex’s rescue (FCMC 2009a, 1).

According to a parliamentary investigation, many of the documents related to the sale process of Citadele were assigned the status “limited availability information” (Parliament of Latvia 2015, 5). The parliamentary investigation commission unsuccessfully tried to declassify these documents to inform the public of the sale process (Parliament of Latvia 2015).

After the split, Citadele and Reverta published annual reports containing information on share capital and the sales process.

Source and Size of Funding

1

Latvian authorities acquired 85% of Parex from the two majority shareholders for LVL 2.00 (EC 2009a).

According to Section 3 of the Restructuring Communication, banks and their stakeholders had to contribute to restructuring as much as possible to reduce State Aid, competition distortion, and moral hazard. Latvian authorities intended to fund restructuring with the proceeds from the sale of bank assets and interest paid on term deposits (see Decker forthcoming-b) (EC 2010).

On December 23, 2008, the IMF announced a 27-month Standby Arrangement for SDR 1.5 billion (EUR 1.7 billion) under the EFM. Additional support came from multilateral organizations and other European countries (see Key Design Decision No. 2, Part of a Package, and No. 13, Cross-border Cooperation) (IMF 2009).

The Treasury issued loans to the LPA so that the latter could recapitalize Parex: LVL 271.4 million lent in 2009 and LVL 144 .0 million lent in 2010FAccording to the Treasury’s annual report, the LPA repaid LVL 91.6 million in 2009 (Treasury 2010). However, it is unclear whether the LPA repaid these loans in full, and research has not uncovered the LPA’s annual reports for 2009 and 2010. (Treasury 2010; Treasury 2011).

The EBRD also contributed to Parex’s restructuring through subscriptions of share capital and the provision of a subordinated loan (see Key Design Decision No. 15, Duration) (Citadele 2011; EC 2009c; Parex 2009i).

Including capital and liquidity support, Latvia’s support for Parex peaked at EUR 1.7 billion. As of April 2015, unrecovered state aid totaled EUR 784 million: EUR 35.0 million in Citadele’s subordinated capital (4.5% of total unrecovered state aid), EUR 294.0 million in Reverta’s share capital (37.5% of total unrecovered state aid), and EUR 455.0 million in bonds in Reverta converted from liquidity support (58.0% of total unrecovered state aid) (Parliament of Latvia 2015).

According to a parliamentary report published in December 2015, the state estimated EUR 500 million EUR 600 million in losses (Parliament of Latvia 2015). According to Reverta’s annual report, the state had lost EUR 428.8 million in share capital and EUR 22.5 million in liquidity support for a total loss of EUR 451.3 million as of December 2022 (Reverta 2023).

Approach to Resolution and Restructuring

1

Restructuring and Split

The restructuring plan approved by the EC in September 2010 outlined a split of Parex into a newly established good bank called Citadele and a remaining bad bank, later called Reverta (EC 2014a; Parex 2011). Citadele would focus on three core business segments in the Baltics: corporate, retail, and wealth management. Latvian authorities aimed to make Citadele profitable in a sustainable manner by reducing the size of its balance sheet. Reverta would keep the remaining noncore and nonperforming assets in addition to the senior syndicated loans and legacy subordinated liabilities (EC 2010). Reverta’s goal was to maximize the recovery of state aid (Parex 2011). See Figure 3 for the split between the remaining bad bank and the new good bank.

Per the initial EC authorization of capital injections into presplit Parex, Latvian authorities’ stated purpose was to maintain regulatory minimum capital requirements, an 8% CAR; the FCMC raised presplit Parex’s minimum CAR to 11% on March 25, 2009 (EC 2008a; EC 2009b; FCMC 2009b).

Capital and liquidity support were also restructured with the split. Citadele took LVL 50.3 million of Tier 2 capital, and Reverta took the equity capital injected on March 29, 2009. At the time of the split, 16 term deposits were in effect for EUR 635 million (LVL 446 million). Eight of those deposits went to Citadele, four of which worth LVL 12 million were already terminated. Citadele’s remaining four term deposits were converted into equity for a recapitalization of LVL 103 million (EC 2010; Treasury 2011). Reverta took the other eight term deposits, which could be converted to capital in the years 2010–2013 up to a maximum amount of LVL 218.7 million (EC 2010; EC 2014b). With the amended restructuring plan in August 2012, this amount was reduced to LVL 118.7 million (EC 2012; EC 2014b). Ultimately, Reverta converted only LVL 49.5 million of its state term deposits to capital. Because this conversion was lower than the restructuring plan’s allocation, the EC questioned whether Reverta had violated State Aid authorization but ultimately decided that Reverta had not (EC 2014b). In December 2011, all of Reverta’s outstanding term deposits were converted to debt securities (Parex 2012; Reverta 2013). These debt securities remained with Reverta when the bad bank later went into liquidation in 2017 (Reverta 2018).

Figure 3: Pro Forma Balance Sheets of Parex, Reverta, and Citadele

Sources: Citadele 2011; Parex 2010b; Parex 2011.

Sources: Citadele 2011; Parex 2010b; Parex 2011.

Citadele after the Split

The LPA began the process of selling Citadele on July 16, 2013. The government approved a strategy for finding investors on December 17, 2013. Criteria considered throughout the sales process included: price, terms of the transaction, quality of the investor (stability and predictability), and ability to ensure Citadele’s ongoing development. The LPA also considered unspecified geopolitical concerns and the views of Latvia’s security institutions (Citadele 2015b).

The LPA administered the process with the help of Société Générale and Linklaters. The LPA approached approximately 100 investors, and 14 investors expressed interest. Eight investors submitted nonbinding offers after signing confidentiality agreements and examining an information memorandum. Five investors conducted due diligence and updated their offers. The Latvian government approved further negotiations with three investors who conducted confirmatory due diligence. The government chose to continue final negotiations only with Ripplewood (see Summary Evaluation) (Citadele 2015b).

On November 5, 2014, the LPA signed a purchase agreement with Ripplewood. Ripplewood also submitted an application and documents to the FCMC to obtain a substantial participation permit. The FCMC would submit an opinion and proposal to the European Central Bank (ECB) under the unified supervisory mechanism. The ECB would make the final decision on whether to issue a permit (Citadele 2015a).

On April 20, 2015, the LPA closed the sale transaction of Citadele to Ripplewood and a group of 12 international investors for a 75% stake in Citadele, totaling EUR 74.7 million. The EBRD retained a 25% stake in Citadele (Citadele 2015a; Citadele 2015b). The new shareholders increased Citadele’s equity capital by EUR 10 million (Citadele 2015b).

Reverta after the Split

All cash resources recovered by Reverta went toward repaying syndicated loans and then State Aid (IMF 2013; Parex 2011). According to Reverta’s annual report for 2010, management did not expect Reverta to make a profit from the bad bank’s activities, considering the restructuring plan (Parex 2011).

On November 30, 2010, the Cabinet of Ministers decided to increase Reverta’s share capital by LVL 9.7 million. The LPA acquired these shares, thus increasing the government’s stake. As of December 31, 2010, the shareholder structure of Reverta comprised: the LPA (81.8%), the EBRD (14.6%), and minority shareholders (3.6%) (Parex 2011).

In March 2012, the FCMC canceled the bad bank’s banking license. Subsequently, in May 2012, the bad bank was officially renamed Reverta (EC 2014a; OECD 2016; Treasury 2013).

In 2017, the LPA bought the EBRD’s stake in Reverta (March), initiated Reverta’s liquidation (July), and created a new limited liability company called REAP to manage Reverta’s assets and claim rights (November) (see Key Design Decision No. 15, Duration) (LPA 2018; Reverta 2017; 2018).

Treatment of Creditors and Equity Holders

1

Initial Investment Agreement

At the beginning of November 2008, the two majority shareholders of Parex submitted a request to the State Chancellery for state aid (Parliament of Latvia 2015). The FCMC, Ministry of Finance, BoL, and majority shareholders met at this time to discuss the government takeover of Parex. Although it was possible for the government to forcibly take control, complex legal procedures would have protracted the process and delayed state aid. Thus, Latvian authorities decided to engage the two majority shareholders, Kargins and Krasovickis, in an investment agreement (FCMC 2009b).

On November 10, 2008, Parex’s majority shareholders transferred 51% of the bank’s shares to LHZB. Though the two majority shareholders still technically owned 34%, LHZB exercised the voting rights for this 34% of shares as well (EC 2008a).

Pursuant to the November 10 agreement for 51%, at the request of LHZB or the government, Kargins and Krasovickis had to cover any losses that were not duly reflected in Parex’s financial reports at the closing date of the agreement (EC 2008a). PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) investigated the authenticity of financial statements submitted by the two majority shareholders under the initial investment agreement (FCMC 2009b).

Kargins and Krasovickis were entitled to repurchase shares from LHZB for LVL 2.00, plus the sum equal to 1% of the whole amount of funds granted under the agreement to the bank, provided that:

- At least 12 months elapsed from the signing date of the agreement;

- Parex repaid all subordinated loans that it received from the government;

- All the guarantees provided by the government with respect to the liabilities of Parex had been released;

- Parex had covered all expenses of the government and LHZB with respect to the financial assistance it received per the initial agreement;

- The government had not already sold Parex’s shares to a third-party investor. (EC 2008a)

Kargins gave an interview with the Latvian newspaper Dienas Bizness after the announcement of the initial agreement. Kargins said that it was the correct move to ask the government for help, and the government subsequently decided the structure of assistance. Kargins said that, under that initial agreement, he and Krasovickis had the right of first purchase once the government decided to sell the 51% stake (BBC 2008a).

The remaining 15% minority shareholders were not affected by the agreement (Anderson 2008a; EC 2008a). Swedish fund manager East Capital and Swedish bank Svenska Handelsbanken AB were among the minority shareholders (Anderson 2008a; FCMC 2009b).

On November 14, 2008, creditors of the senior syndicated loans, amounting to EUR 775 million, were preparing to announce a default event, which meant that these loans would have become due immediately rather than on their maturity dates in February 2009 and June 2009 (see Figure 4) (EC 2008a). Parex lost access to wholesale funding, and the bank did not have enough own resources to repay the loans. Latvian authorities debated the pros and cons of restructuring the loans and decided to fully repay them to avoid hurting market perception of Latvia (IMF 2013). Thus, authorities negotiated with these creditors to maintain the maturity dates in February and June, provided that the government issued a guarantee for these loans (see Key Design Decision No. 2, Part of a Package) (EC 2008a).

Figure 4: Parex’s Senior Syndicated Loans Due in 2009

Note: EURIBOR refers to the Euro Interbank Offered Rate.

Note: EURIBOR refers to the Euro Interbank Offered Rate.

Source: EC 2008.

Since LHZB’s initial takeover, Parex negotiated with its lenders to extend the terms of its senior syndicated loans (Parex 2009a; Parex 2009c; Reuters 2009a). On March 11, 2009, Parex announced the finalized repayment schedule (see Figure 5) (Parex 2009f; Parex 2009h; Treasury 2010). The creditors included HSBC, Mizuho Corporate Bank Ltd., Raiffeisen, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp., and Commerzbank (Reuters 2009c).

Figure 5: Revised Repayment Schedule of Senior Syndicated Loans

Sources: Cabinet of Ministers 2009a; Parex 2009f; Parex 2009h; Treasury 2010.

Sources: Cabinet of Ministers 2009a; Parex 2009f; Parex 2009h; Treasury 2010.

Amended Investment Agreement

On December 3, 2008, LHZB took over 85% of Parex’s shares, thus removing the two majority shareholders, per the amended agreement. After the amended agreement, the two major shareholders were no longer entitled to first purchase of their shares back from LHZB (EC 2009a).

Most minority shareholders were not immediately affected by the amended agreement on December 3, 2008, since LHZB specifically took the shares belonging to the two majority shareholders, Kargins and Krasovickis (Anderson 2008a; EC 2009a). One of the largest minority shareholders, Handelsbanken, volunteered to sell its 0.3% stake to LHZB for EUR 0.01 (FCMC 2009b; Kolyako 2008a). According to the Baltic Course, Handelsbanken exited to avoid a conflict of interest in case the Swedish government’s loan was used to strengthen Latvian banks (see Key Design Decision No. 13, Cross-border Cooperation) (Kolyako 2008a).

Split into Good and Bad Banks

Before the split, Parex had EUR 2.5 billion in customer deposits as of June 30, 2010 (Parex 2010b). After the split, at year-end 2010, Reverta had EUR 352.1 million in customer deposits and Citadele had EUR 1.6 billion in customer deposits (Citadele 2011; Parex 2011).

The senior syndicated lenders remained with the bad bank after the split (EC 2010). All the loans were repaid by May 2011: The first was repaid with government liquidity support, and the second and third were repaid from the bank’s own resources (IMF 2013).

After the split into good and bad banks, Citadele and Reverta, respectively, the original minority shareholders of Parex remained with bad bank, Reverta (see Figure 6). The subsequent recapitalizations of Reverta by the government and the EBRD diluted minority shares in Reverta from 15% to 3% (EC 2010).

Figure 6: Citadele’s and Reverta’s Shareholder Structures after the Split on August 1, 2010

Sources: EC 2010; EC 2014b.

Sources: EC 2010; EC 2014b.

In its decision on September 15, 2010, the EC said that Kargins and Krasovickis adequately bore the burden of Parex’s failure because they were wiped out as equity holders after the government acquired their shares for a total of LVL 2.00. The minority shareholders also bore this burden when their shares were diluted from 15% to 3%, according to the EC. The EC said that this use of bail-in sufficiently addressed burden sharing and “[served] as a valuable signal against moral hazard” (EC 2010). Per an EC decision in July 2014, Latvian authorities clarified that the state would not pay any interest, dividends, or coupons on existing capital instruments to anyone other than the Latvian state or EBRD until all State Aid was fully repaid (EC 2014b). Reverta did not pay dividends on its share capital from 2010–2013 and 2016–2018, according to its annual reports. Reverta’s annual reports from 2014–2015 and 2020–2022 do not mention dividends proposed or paid to shareholders.

Treatment of Clients

1

Per behavioral restrictions outlined in the EC authorization, Citadele could not grant new loans to clients from CIS countries and clients whose ultimate beneficiaries were from CIS countries until the closing of the sale of its CIS loans (see Key Design Decision No. 14, Other Conditions) (EC 2010).

Treatment of Assets

1

Good Bank: Citadele

The government split assets according to a “good-out” scenario where the good bank, Citadele, would have a Baltics focus (corporate, retail, and wealth management) and a resilient capital base under Latvian regulatory oversight. To this end, Citadele received all core assets and some noncore assets: Baltic performing loans, CIS performing loans, and branches in Sweden and Germany. This was considered an asset relief measure because Citadele was relieved from the burden of potential losses left behind in the bad bank. Until its sale closing from the LPA to private ownership, Citadele remunerated the government for asset relief each year during which Citadele’s CAR was at least 12% on a solo basis and at least 8% at a group level, provided that this amount did lead to Citadele showing losses during that year (EC 2010; EC 2012). The remuneration took the form of costs in the profit and loss account (that is, before the establishment of the annual net income) up to the amount of estimated losses in the worst-case scenario (that is, the sum of liquidity measures provided by the government potentially lost at the end of the assets’ realization) (EC 2010).

As a result of the split, Citadele’s assets were reduced by about 60%, and its market presence in all core markets was reduced by more than 50%, compared to pre-crisis Parex (EC 2010).

In March 2012, Latvian authorities requested permission from the EC to raise the CAR at which asset remuneration was triggered (see Key Design Decision No. 14, Other Conditions). The EC approved this change on August 10, 2012 (EC 2012).

Bad Bank: Reverta

The bad bank, Reverta, received the remaining noncore and nonperforming assets: Baltic NPLs, CIS NPLs, and loans to legacy shareholders. After the split, the LPA planned to sell and run off all of Reverta’s assets from 2010 to 2017; the resulting inflow would go toward repaying the state term deposits (see Decker forthcoming-b) (EC 2010).

Treatment of Board and Management

1

Initial Investment Agreement

According to the EC, Parex’s decision-making processes were centralized with the two majority shareholders before the government’s takeover (EC 2010). Valērijs Kargins was the president and board chairman of Parex in addition to being one of the two majority shareholders (BBC 2008a; Parex 2011). The other majority shareholder, Viktors Krasovickis, was also a board member (FCMC 2009b; Parex 2011). They were removed from Parex’s management when the government took a 51% stake in the bank in November 2008 (BBC 2008a; FCMC 2009b).

The board chairman of LHZB, Inesis Feiferis, became the president of Parex after the government took over in November 2008. Feiferis had been working with the Latvian Association of Commercial Banks and the BoL to create a stabilization fund for the financial sector in response to the crisis (BBC 2008b).

Amended Investment Agreement

On December 5, 2008, the council of Parex elected four board members (FCMC 2009b). Nils Melngailis became chairman and CEO of Parex after he left telecoms operator Lattelecom following a failed privatization effort (Baltic Times 2008; FCMC 2009b; Reuters 2008). In an announcement, then–Finance Minister Atis Slakteris said that the “former owners did not act responsibly enough to stabilise the situation in the bank” (Reuters 2008). The government removed Kargins and Krasovickis from Parex’s board (Reuters 2008).

On December 19, 2008, Parex announced the election of a new council to represent the interest of the Republic of Latvia as the indirect majority shareholder (FCMC 2009b; Parex 2008).

Parex–Reverta Management

On March 10, 2009, Parex announced two new board members who joined the other members of Parex’s board, including chairman and CEO Melngailis (Parex 2009g).

Parex elected entirely new management in spring and summer 2010. On April 6, 2010, shareholders elected a new council during an extraordinary general meeting. On July 30, 2010, right before the split, shareholders elected a new management board. The council and management board stayed with the bad bank after the split (Parex 2011).

Legal Action against the Majority Shareholders and Senior Management

On July 30, 2010, Parex filed a claim against the former board members and majority shareholders, Valērijs Kargins and Viktors Krasovickis, for compensation for damages to the bank greater than LVL 62 million (FCMC 2009a; Parex 2011; Republic of Latvia 2011). Parex alleged that the former majority shareholders conducted loan and deposit agreements from January 1995 to December 2008 that were not in the best interest of the bank. Parex alleged that these terms were very different than terms one would usually find in agreements concluded by ostensibly unrelated parties (FCMC 2009a). On August 16, 2010, the Riga District CourtFIn Latvia, the hierarchy of courts is: (1) city or district courts, (2) regional courts, and (3) the Supreme Court (EU 2023). took up the claim (Parex 2011). In October 2016, the Supreme Court of Civil Cases decided that Kargins and Krasovickis had to pay EUR 4.3 million to Reverta and cover the cost of litigation, an additional EUR 230,550. In August 2022, the Riga Regional Court ordered Kargins and Krasovickis to pay EUR 81.2 million to REAP, the subsidiary of the LPA that took over Reverta in 2017 (Baltic Times 2022; Reverta 2018). The Riga Regional Court ruling came into force in December 2022, as reported by the Baltic Times (Baltic Times 2022).

Citadele’s Management

After the split, Citadele had a management board and supervisory board to ensure high corporate governance standards (EC 2010).

The new bank had three management and governance bodies. Citadele’s management board was appointed at the time of the split. Citadele’s new council and supervisory board were appointed on August 11, 2010 (Citadele 2011).

Cross-Border Cooperation

1

Along with the SBA announced with the IMF for SDR 1.5 billion (EUR 1.7 billion), multilateral organizations and other European countries additionally provided support (see Figure 7) (IMF 2009). In the interim between the SBA announcement and when the loans took effect, Latvia used already-established short-term swap facilities up to EUR 500 million with the central banks of Denmark and Sweden (EIU 2008).

The design of the SBA involved other partners. The EC participated in program design with regard to fiscal and financial matters. The World Bank weighed in on social safety nets and the financial sector legal framework. The EBRD was specifically involved in the resolution of Parex. A representative from the Swedish Ministry of Finance regularly joined IMF program missions to Latvia, given the importance of Swedish banks in the Latvia (IMF 2013).

Figure 7: Commitments by Multilateral Organizations and Other European Countries as of January 2009

Source: IMF 2009.

Source: IMF 2009.

Other Conditions

1

Initial Investment Agreement

Latvian authorities placed behavioral constraints on Parex to avoid undue distortions of competition for EC compliance (see Figure 8). The FCMC monitored Parex’s compliance with these restrictions and took necessary action in the event of noncompliance. The FCMC also was responsible for notifying the EC (EC 2008a).

Figure 8: Initial Behavioral Restrictions on Parex

Source: EC 2008a.

Source: EC 2008a.

Amended Investment Agreement

Per the amended agreement on December 3, 2008, the behavioral constraints on Parex remained essentially the same except for one change in order to match the behavioral constraints imposed on banks under the Latvian guarantee scheme (EC 2008b; EC 2009a). In effect, Latvian authorities no longer placed balance sheet restrictions on Parex’s mortgaged loan portfolio and loan portfolio (EC 2009a).

Restrictions on Reverta after the Split

The government forbade Reverta from engaging in any new activities that were unnecessary for Reverta’s primary task of managing and selling assets. To this end, Reverta could not take new deposits from the public, grant new loans to customers, and grant further advances on existing loans. Under certain circumstances, Reverta could grant further advances on loans if this would increase the probability of being repaid; such advances could not exceed 5% of the previous year’s loan portfolio (EC 2010).

Restrictions on Citadele after the Split

In the restructuring plan approved by the EC on September 15, 2010, the government imposed certain restrictions on Citadele until full repayment of state aid and sale closing that would return Citadele to the private sector (see Figure 9) (EC 2010).

Figure 9: Behavioral Restrictions on Parex at the Time of the Split

Sources: EC 2010; EC 2012.

Sources: EC 2010; EC 2012.

On March 6, 2012, Latvian authorities submitted three requests to the EC on the issue of CIS loans: (1) extend the deadline to divest all CIS loans, (2) increase the CAR amount at which asset remuneration was triggered, and (3) allow carryover of the previous years’ unused caps on lending, while respecting market share caps (EC 2012).

Regarding the extension, Citadele’s CIS loan portfolio consisted of 22 related groups of clients or 39 loans, as of June 30, 2011. The loan portfolio was running down faster than Citadele estimated in the restructuring plan, since lenders were opting for early redemption to Citadele and refinancing with other banks. Thus, a forced sale of Citadele’s CIS loan portfolio by a divestiture trustee would likely have been discounted and had a negative impact on Citadele’s capital. The EC agreed with Latvia’s assessment; the EC furthermore said that Citadele could potentially reduce or entirely eliminate potential losses on the loans if the bank were allowed to run down the loans on an extended timeline. Since the request did not significantly alter the restructuring plan, the EC granted the deadline extension (EC 2012).

Regarding the asset relief remuneration trigger at CAR 12% and 8%, Latvia authorities argued that the trigger should better consider Basel II and forthcoming Basel III requirements. They proposed new asset remuneration triggers for Citadele to the EC, as long as the relevant amounts did not lead to losses on the bank’s or group’s CAR: the current minimum regulatory requirement as determined by the FCMC + 0.5% buffer, or the future minimum regulatory requirements as determined by the FCMC up to one year before they are effectively in force +0.5% buffer. The EC approved the proposed changes, considering that the earlier repayment of liquidity support from the government would counterbalance the changes in terms of burden sharing (EC 2012).

Regarding the lending caps, Citadele’s lending activity was not as high as the restructuring plan envisioned, hurting the bank’s profitability. Latvian authorities gave two explanations as to why the bank’s loan portfolio declined 9.4% from the end of 2010 until March 2012. First, presplit, Parex could not engage in new lending, thus Citadele could start new lending only after August 1, 2010. Second, Citadele experienced unexpectedly high loan redemptions. Latvian authorities proposed that lending caps not fully utilized in a calendar year could be rolled forward in Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, while still respecting market share caps. To mitigate competition distortion, Latvian authorities offered to close the Swedish branch of Citadele with deposit-taking operations by December 31, 2012. The EC acknowledged that Citadele could have given larger volumes of lending in 2010 and 2011 than the bank effectively provided and that redemptions were higher than expected. Thus, the EC allowed Citadele to roll forward unused cap amounts while respecting market share caps (EC 2012).

Duration

1

According to a parliamentary report published in December 2015, the state estimated EUR 500 to EUR 600 million in losses (Parliament of Latvia 2015). According to Reverta’s annual report, the state had lost EUR 428.8 million in share capital and EUR 339.7 million in liquidity support for a total loss of EUR 767.5 million as of December 2022 (Reverta 2023)

Parex: Presplit

The EBRD began to consider investing in Parex as early as December 2008 and conducted due diligence in January 2009 (Anderson 2008b; Kolyako 2008b). The EBRD postponed negotiations over its investment in Parex after the Latvian government fell in February 2009. However, an EBRD spokesperson said that there was no change in their position and that they remained interested in investing in Parex (Reuters 2009b).

On April 16, 2009, the EBRD entered an investment agreement with the LPA (Cabinet of Ministers 2009b; EBRD 2009; EC 2009b; FCMC 2009a). The EBRD would be a long-term investor and participate in the development of the bank; the ultimate goal was to return Parex to the private sector (EBRD 2009; EC 2009c). Per the agreement, the EBRD would pay LVL 1.00 per share for 25%+1 of ordinary shares with voting rights in Parex for LVL 59.5 million (EBRD 2009; EC 2009b; FCMC 2009a; Parex 2011). The EBRD would also provide a subordinated loan of EUR 22 million, qualifying as Tier 2 capital, which could be transferred into shares or recovered as a loan (EBRD 2009; FCMC 2009a). The EBRD would be represented at Parex’s supervisory board with a nominee director (EBRD 2009). Also, per the agreement, the Ministry of Finance guaranteed a maximum of LVL 89 million of the LPA’s liabilities. The deal closed on September 3, 2009 (EC 2009c; Parex 2009i).

On September 11, 2009, the EBRD injected EUR 18.4 million into Parex as a subordinated loan, qualifying as Tier 2 capital (EBRD 2009; Parex 2009i).

Citadele: Good Bank

On July 30, 2010, the EBRD acquired from the LPA 25% of Citadele’s share capital plus one voting share (see Figure 10) (Citadele 2011).

Figure 10: Citadele’s and Reverta’s Shareholder Structures as of December 31, 2010

Sources: Citadele 2011; Parex 2011.

Sources: Citadele 2011; Parex 2011.

Latvia committed to enter a binding sale and purchase agreement for Citadele by December 31, 2014, and to complete the transaction by December 31, 2015. If Latvia did not enter an agreement by the 2014 deadline, the government would have appointed a divestiture trustee to sell Citadele by December 31, 2015 (EC 2010).

On November 5, 2014, the LPA signed a purchase agreement for Citadele with its eventual acquirers. On April 20, 2015, the LPA closed the sale transaction of Citadele for EUR 74.7 million to Ripplewood (22.4%) and a group of 12 international co-investors (52.6%)—including Baupost Group (hedge fund), Paul Volcker (former chairman of the US Federal Reserve), and James D. Wolfensohn (former president of the World Bank) (Citadele 2014; Citadele 2015b). The EBRD retained a 25% stake in Citadele. The new shareholders increased Citadele’s equity capital by EUR 10 million (Citadele 2015b). Upon sale closing, Citadele no longer had to observe the behavioral restrictions imposed by the government to limit competition distortion (Citadele n.d.).

On January 4, 2017, Citadele repaid its subordinated loan from the LPA, thereby settling its remaining obligations to the Latvian government (Reverta 2018).

Reverta: Bad Bank

The LPA planned to sell and run off all of Reverta’s assets from 2010 to 2017 (EC 2010).

The LPA bought the EBRD’s stake in Reverta for EUR 1 on March 7, 2017, per the restructuring plan and a decision by the Cabinet of Ministers on December 15, 2014 (LPA 2018; Reverta 2017). Afterward, the LPA had a 96.9% stake and minority shareholders had a 3.1% stake in Reverta (Reverta 2017).

The liquidation of Reverta began on July 6, 2017. Later, on November 17, 2017, the LPA created a new subsidiary and limited liability company, REAP, for the sole purpose of managing Reverta’s assets and claim rights (Reverta 2018). REAP represented Reverta in court cases initiated against its debtors in the courts of the Republic of Latvia, Russian Federation, and Republic of Cyprus (LPA 2019; Reverta 2022). By the end of 2017, the LPA had written off its entire investment in Reverta share capital. REAP sold most of the real estate assets taken over by Reverta during the course of 2018 (LPA 2019).

As of the writing of this case, Reverta was still in liquidation. Reverta had a total asset value of just EUR 1.7 million as of December 31, 2022 (LPA 2023).

Key Program Documents

-

(Baltic Legal n.d.) Baltic Legal. n.d. “Mortgage and Land Bank of Latvia.” Accessed September 18, 2023.

Webpage containing information on the establishment and mission of LHZB.

-

(Citadele n.d.) AS Citadele banka (Citadele). n.d. “About Us: History.” Accessed March 21, 2023.

Webpage containing Citadele’s origin and history.

-

(EU 2023) European Union (EU). 2023. “National Ordinary Courts: Latvia,” May 2, 2023.

Webpage containing information on Latvia’s legal system (translated by the EU).

-