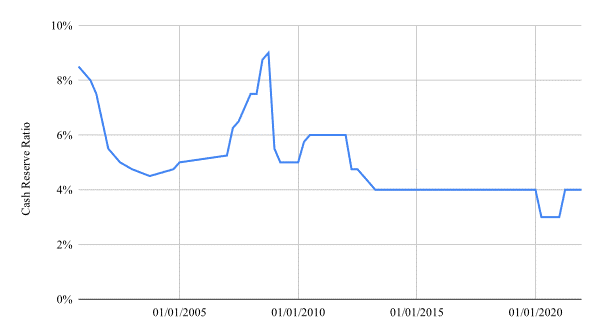

Reserve Requirements

India: Reserve Requirements, GFC

Purpose

To “alleviate the pressures brought on by the deterioration in the global financial environment” (RBI 2008v)

Key Terms

-

Range of RR Ratio (RRR) Peak-to-TroughCash reserve ratio: 9%–5% Statutory reserve ratio: 25%–24%

-

RRR Increase PeriodCash reserve ratio: September 2004–July 2008 Statutory reserve ratio: N/A

-

RRR Decrease PeriodCash reserve ratio: October 2008–January 2009 Statutory reserve ratio: November 2008

-

Legal AuthorityReserve Bank of India Act, Section 42; Banking Regulation Act, Section 18

-

Interest/Remuneration on ReservesUnremunerated

-

Notable FeaturesNo rate difference for various liabilities or currency denominations Banks had to hold reserves against some types of borrowings in addition to deposits

-

OutcomesCRR cuts released USD 32.7 billion; SLR cuts released USD 8.2 billion

As international funding sources dried up during the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 (GFC), businesses in India sought funds from domestic financial institutions, straining banks and lifting short-term lending rates. The liquidity pressure, coupled with sharp asset price corrections and rupee depreciation, restricted credit expansion in India. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) responded with a suite of liquidity measures, including cuts to its two reserve requirement ratios, the cash reserve ratio (CRR) and the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR). The RBI cut the CRR over the course of four months from October 2008 to January 2009, lowering the ratio from 9% to 5%. It cut the SLR once, from 25% to 24%, in November 2008. The RBI’s CRR and SLR cuts applied to most commercial banks and certain cooperatives and regional banks. The RBI did not remunerate CRR reserves, and it did not apply different ratios to different liabilities. The cuts released USD 32.7 billion into India’s financial system. The RBI raised the SLR to its pre-crisis levels in October 2009 and began raising the CRR again in March 2010. The International Monetary Fund said the cuts were “quick,” “fully warranted,” and led to looser credit conditions in India, in combination with other liquidity measures.

The Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 (GFC) affected the Indian banking sector indirectly (Kumar and Vashisht 2012; RBI 2009g). The country’s financial institutions were not significantly exposed to US subprime lending, and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) banned complex securitization structures and imposed higher regulatory requirements on commercial bank lending to the housing industry. But as international funding sources dried up, businesses in India sought funds from domestic financial institutions. This strained banks, and short-term lending rates rose sharply, with the interbank call money rate spiking to 20% in October 2008 and remaining high for weeks (Kumar and Vashisht 2012). The liquidity pressure, coupled with sharp asset price corrections and rupee (INR) depreciation, restricted credit expansion in India (Kumar and Vashisht 2012; RBI 2009g).

The RBI responded to the worsening liquidity situation with regular open market operations (OMOs) involving government security purchases; the acquisition of securities through the Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF); various special refinancing facilities and schemes; and the reduction of key rates, including the repurchase agreement (repo) rate and the reverse repo rate (Kumar and Vashisht 2012; RBI 2009g).

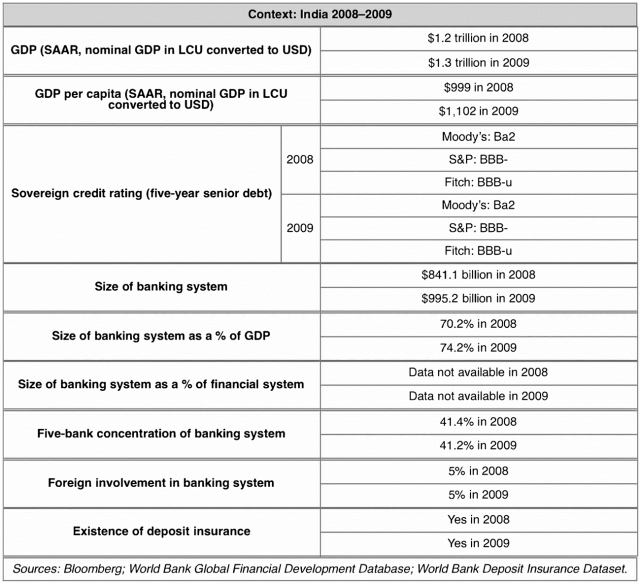

The RBI also reduced the cash reserve ratio (CRR), which dictates how much cash banks must maintain with the RBI, from 9% to 5% of liabilities over the course of four months, from October 2008 to January 2009. Before September 2008, the RBI had gradually raised the CRR to slow credit growth (RBI 2009g, 4; 46). After the cuts in late 2008 and early 2009, the RBI began raising the CRR again in 2010 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Cash Reserve Ratio Before, During, and After the Global Financial Crisis

Source: Reserve Bank of India data via Bloomberg.

The RBI applied the same CRR to liabilities denominated in domestic and foreign currencies and to different categories of liabilities. The RBI applied the CRR to a bank’s net demand and time liabilities (NDTL) (RBI 2006b; RBI 2008a). The RBI did not pay interest on CRR balances (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42, 1A, n. 3).

In addition to a specific level of cash reserves, all banks had to meet a Statutory liquidity ratio (SLR). The SLR prescribed the portion of NDTL that banks had to hold in other reservable assets, which were government-approved securities. On September 16, 2008, the RBI announced that scheduled banks could pledge up to 1.0% of their SLR-eligible NDTL to the Liquidity Adjustment Facility without penalty on a temporary basis. This de facto SLR cut was formalized on November 3, when the RBI announced a “permanent” 100-basis-point (bp) SLR cut, from 25% to 24%, for all scheduled banks (RBI 2008t).

All scheduled banks in India are required to maintain CRR reserves with the RBI, and both scheduled and unscheduled banks are required to meet a minimum level of SLR assets (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42). The RBI deems banks “scheduled” if they meet certain regulatory requirements, chief among them that paid-up capital and reserves are equal to or more than INR 500,000 (USD 10,647) FPer the International Monetary Fund, USD 1 = INR 46.96 on October 1, 2008. and that the bank does not act in ways that are detrimental to its depositors (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42[6][a]). Scheduled commercial banks held approximately 90% of the banking system’s assets in 2009. The CRR cuts also applied to specific scheduled cooperative banks and regional rural banks; the RBI did not issue circulars cutting the SLR for nonscheduled banks (RBI 2008c; RBI 2008t; RBI 2009e).

The RBI held the CRR steady from January 2009 to March 2010, when it began raising the ratio to normalize policy after the GFC recovery and to cool rising inflation (RBI 2010a).

The CRR cuts released USD 32.7 billion into the Indian financial system (Kumar and Vashisht 2012). The RBI also lowered the SLR, releasing USD 8.2 billion. In total, the RBI’s interventions, which are enumerated in Key Design Decision No. 2, Part of a Package, released USD 87.5 billion.

Researchers have done little analysis of the RBI’s four CRR cuts in late 2008 and early 2009. International Monetary Fund (IMF) analysts said in 2009 that the RBI’s cuts in interest rates, the CRR, and the SLR were “quick,” “fully warranted,” and led to looser credit conditions (IMF 2009).

Various Indian industry officials stated publicly in early 2009 that the RBI’s policy rate cuts, including the CRR, had not led to adequate credit expansion. Commerce and Industry Minister Kamal Nath told reporters that fresh liquidity had not reached “cash-starved industry and consumers” (Dhasmana 2009; Roy and Bhoir 2009). Some journalists and RBI officials argued at the time that the perceived riskiness of businesses in India was the source of constrained credit growth, rather than ineffective liquidity policy (RBI 2009g; Tarapore 2009). Indian dealers told Reuters News staff that banks “were more comfortable lending overnight to each other or parking with the central bank via the reverse repo window” (Reuters News Staff 2009).

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

1

In response to a sharp contraction in liquidity, the Reserve Bank of India cut its cash reserve ratio four times between October 2008 and January 2009 (RBI 2009g). In announcing the first adjustment in October, an RBI press release said the CRR cut intended to “alleviate the pressures brought on by the deterioration in the global financial environment” (RBI 2008v).

The RBI also reduced its statutory liquidity ratio from 25% to 24% on November 8, 2008.FCommercial banks held SLR securities—liquid assets including cash, gold, and specific unencumbered securities—at 27.8% of their net demand and time liabilities at end-March 2008 and 28.1% at end-March 2009 (RBI 2009g). Banks could pledge their excess SLR assets as collateral to borrow from the RBI.

The RBI later said that the combination of the lower reserve ratios and lower interest rates would “[support] demand expansion with a view to arresting the moderation in growth” (RBI 2009g).

Part of a Package

1

The RBI responded to deteriorating liquidity conditions in 2008 and 2009 with a package of credit-easing measures. It revised its Liquidity Adjustment Facility—cutting the LAF’s repo and reverse repo rates, adding an additional LAF (the so-called Second Liquidity Adjustment Facility, or SLAF), and raising the maximum amount of funds banks could tap through the LAF (RBI 2009g). Banks could also exclude LAF loans that they used to support nonbank financial institutions and mutual funds from the calculation of their SLRs.FExcess SLR securities served as the only collateral for the LAF (RBI 2014). The RBI marshaled support for mutual funds and nonbank financial institutions after these firms, which were heavily exposed to commercial paper and asset-backed securities, experienced withdrawals, and the firms that depended on this market-based funding turned to banks for liquidity (Bandyopadhyay 2008). In its initial announcement on October 15, 2008, the RBI limited the amount eligible for exclusion to 0.5% of the bank’s net demand and time liabilities, and on November 1, raised this to 1.5% (RBI 2008o; RBI 2009g).

In its OMOs, the RBI began purchasing government securities through auctions, as a complement to its order-matching process (RBI 2009g). The RBI also repurchased securities that the government created and issued under its Market Stabilization Scheme (MSS), a program that policymakers enacted in 2004 to sterilize capital inflows (RBI 2009g; Thorat 2009).

In total, the RBI’s interventions released USD 87.5 billion (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Liquidity Released by RBI Interventions

Source: RBI 2009g.

Legal Authority

1

All scheduled banks in India are required to maintain cash reserves with the RBI pursuant to Section 42 of the Reserve Bank of India Act (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42). The Indian government in 2006 amended the RBI Act to eliminate constraints on the level of the CRR that the RBI could set. Previously, the central bank was required to set the rate between 3% and 20% (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42, n. 5).

In 2008, nonscheduled, licensed financial institutions were required to hold a cash reserve of 3% of NDTL, which was not subject to revision by the RBI (Banking Regulation Act 1949, Sec. 18; RBI 2008a). In 2012, Parliament changed the law to give the RBI the authority to set the level of the CRR for nonscheduled financial institutions as well (Dhasmana 2009).

According to the Banking Regulation Act, the RBI could prescribe a statutory liquidity ratio, requiring both scheduled and unscheduled banks to maintain a certain percentage of NDTL in assets it would specify through notifications published in India’s official gazette (Banking Regulation Act 1949, Sec. 24; Banking Regulation Act Amendment 2007). This act (as amended in 2007) also capped the SLR at 40% of NDTL.

The RBI deemed banks “scheduled” if they met certain regulatory requirements, chief among them that paid-up capital and reserves are equal to or more than INR 500,000 and that the bank does not act in ways that are detrimental to its depositors (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42[6][a]).FThese institutions are called “scheduled” because they are included in the Reserve Bank of India Act’s second schedule, which is regularly updated as new banks are added and removed (RBI 2021; Sanghvi, Patnaik, and MG 2021). When officials granted a bank scheduled status, the institution could borrow from the RBI and had access to the country’s major clearinghouses (RBI 2007, 9; RBI Act 1934, Sec. 17). Scheduled banks are a segment of a larger pool of financial institutions that are licensed to operate in India (Sanghvi, Patnaik, and MG 2021). Scheduled commercial banks held approximately 90% of the banking system’s assets in 2009 (RBI 2009h; RBI 2010b).

The RBI also had the power to impose marginal reserve requirements on scheduled institutions, but the central bank did not have such marginal requirements in place during the GFC (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42(1A)).

Administration

1

During 2008 and 2009, when the RBI made cuts to its reserve ratios, the RBI governor was responsible for the central bank’s monetary and liquidity policy choices, which included setting the CRR.FIn 2016, the Indian government modified the RBI’s administration rules and created a formal Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) that would make monetary policy decisions thereafter, limiting the RBI governor’s power over policy decision-making (RBI 2017). The RBI governor was assisted in decision-making by a deputy governor specifically responsible for monetary policy.

The RBI also consulted various external stakeholders. A group called the Technical Advisory Committee on Monetary Policy (TACMP), made up of external experts in central banking, finance, and economics, reviewed macroeconomic and monetary developments quarterly and gave the RBI governor advice. Before making monetary policy decisions, the RBI also consulted with banking system representatives, such as trade and industry bodies and financial market participants (RBI 2014).

Governance

1

The Central Board of Directors committee, which met weekly to review financial and economic conditions, supported the RBI governor’s decision-making (RBI 2014, 25). The Central Board governed the RBI’s regular affairs (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 7). The Indian government appointed the Central Board’s members, which consisted of the RBI governor, up to four deputy governors, four directors from local RBI boards (RBI offices in different parts of India), 10 directors from various fields, and two government officials (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 8). The Appointments Committee of the Cabinet had to approve the governor and deputy governor positions (Cabinet Secretariat 1961). It is unclear from available documents exactly what entity nominated the governors and other directors.

The RBI employed certain practices to make its policy decision-making transparent, including the publication of the RBI’s policy rationale and potential or expected outcomes, as well as regular press conferences by the RBI governor after every RBI quarterly policy review.

The central bank helped the Finance minister answer Indian legislators’ questions about the country’s monetary, fiscal, and economic policies. Typically three to four times a year, the RBI governor was summoned to appear before the Parliament’s Standing Committee on Finance (RBI 2014).

Communication

1

The RBI updated its website with circulars and press releases announcing the CRR changes. In one of the press releases, RBI officials said the CRR policy changes would “alleviate the pressures brought on by the deterioration in the global financial environment” (RBI 2008v). The RBI announced the first cut to the CRR on October 6, 2008, then announced the second cut on October 10, 2008, one day before the first cut was slated to take effect (Bandyopadhyay 2008; RBI 2008c; RBI 2008h).FBoth cuts would take effect the following day, on October 11. The only precedents for a cut to the CRR of this size was a 175-bp cut in November 2001 and a 200-bp cut in 1974 (Bandyopadhyay 2008). On October 14, then–Bank of India Chairman and Managing Director TS Narayanasamy stated that the first two CRR cuts, which both took effect on October 11, eased liquidity constraints, “but it is not comfortable,” noting that “[m]ore steps are required and more steps may come from RBI” (Sahu 2008).

At a conference in January 2009, Commerce and Industry Minister Kamal Nath noted that the RBI had “injected liquidity into the banking system, but the liquidity is still not credit,” adding that “the challenge is to make banks lend” (Dhasmana 2009).

In October 2008, roughly one month before the SLR cut was formalized, an RBI official stated that an SLR cut and further cuts to the CRR could be used to ease liquidity constraints in the domestic money market (Reuters News 2008). In its 2008–2009 annual report, the RBI stated that it would consider relaxing SLR requirements for the purpose of helping scheduled banks manage their short-term funding requirements at their overseas offices (RBI 2009g).FIt did so despite concerns about SLR reduction identified in its 2007–08 report—namely, that a lower SLR would shrink the amount of government securities sitting in banks’ held-to-maturity portfolios while a greater amount would be considered available for trading. Contemporaneous reports posited that the appearance of an increased supply of government notes could lower market demand for them at a time when the government was trying to fund a fiscal response to GFC-related disruptions (Hindu Business Line 2008; RBI 2008w).

Assets Qualifying as Reserves

1

The RBI required scheduled financial institutions to hold cash reserves in accounts with the central bank (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42). Nonscheduled financial institutions could hold their cash reserves in cash, current accounts, or accounts with the central bank (Banking Regulation Act 1949, sec. 18 [1]).

The RBI allowed cash, gold, and unencumbered government securities to qualify for the SLR.

On August 10, 2009, the RBI announced the issuance of cash management bills, a new short-term (less than 91-day maturity) instrument akin to treasury bills to meet the government’s cash flow mismatches, and these would be considered government securities for the purposes of the SLR (RBI 2009f).

Reservable Liabilities

1

The RBI calculated both reserve requirements using the institution’s net demand and time liabilities (RBI 2006b; RBI 2008a; RBI 2020). NDTL is a broad calculation of a bank’s liabilities that includes “demand or time deposits or borrowings or other miscellaneous items of liabilities” (RBI 2008a).

The RBI included banks’ borrowings from abroad in the definition of NDTL. The definition also included interest accrued on deposits and other balances due to banks or the public (RBI 2006b). The definition excluded shareholders’ funds (capital) and borrowings from government-owned financial lenders identified in the law (RBI Act 1934, sec. 42 [1][c]).

The definition of NDTL was slightly different for the SLR calculation. The RBI required that banks net their interbank liabilities (interbank deposits and term borrowing), excluding interbank assets, with maturities greater than 15 days and up to one year in their SLR calculations; these were excluded from the CRR per Section 42 of the RBI Act (RBI 2006b; RBI Act 1934, cl. [d]).

The RBI did not apply different reserve ratios to different liabilities. The RBI applied uniform CRRs and SLRs for different kinds of liabilities denominated in both domestic and foreign currencies (RBI 2006b; RBI 2008a).

Computation

1

Scheduled banks were required to hold cash reserves with the RBI directly (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42).FNonscheduled licensed banks could hold their required CRR reserves with the RBI or with themselves (Banking Regulation Act 1949, Sec. 18). As noted in Key Design Decision No. 10, Eligible Institutions, the GFC-era CRR cuts did not apply to these banks. The institutions maintained cash reserves over a two-week span, from Saturday to the second reporting Friday, on an average daily basis (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42; Banking Regulation Act 1949, Sec. 18; RBI 2020, 15).

The RBI calculated the SLR according to the same timeline as the CRR. The SLR also used NDTL for the denominator of the ratio, but the RBI required scheduled banks to include net interbank liabilities, excluding interbank assets, with maturities greater than 15 days and up to one year in their SLR calculations (RBI 2006b). For more details, see Key Design Decision No. 8, Reservable Liabilities.

NDTL were calculated as the sum of: liabilities to the banking system (demand liabilities, time liabilities, and other demand and time liabilities) and liabilities to others in India, less assets within the banking system.

Eligible Institutions

1

Section 42 of the Reserve Bank of India Act requires all scheduled banks to maintain cash reserves with the RBI (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42). The RBI deems banks “scheduled” if they meet certain regulatory requirements, chief among them that paid-up capital and reserves are equal to or more than INR 500,000 and that the bank does not act in ways that are detrimental to its depositors (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42[6][a]). These institutions are called “scheduled” because they are included in the Reserve Bank of India Act’s second schedule, which is regularly updated as new banks are added and removed (RBI 2021; Sanghvi, Patnaik, and MG 2021).

Scheduled banks are a segment of the larger pool of financial institutions that are licensed to operate in India (Sanghvi, Patnaik, and MG 2021).

The RBI and market participants split scheduled banks into two main categories when discussing RBI policy: commercial banks and cooperative banks. Commercial banks are further split into foreign, private, public, and regional rural banks. Cooperative banks are split into urban and rural banks (Sanghvi, Patnaik, and MG 2021).

Each time the RBI announced a CRR cut during the GFC, RBI officials released four separate circulars addressed to different scheduled banking groups: scheduled commercial banks, regional rural banks, rural (or state) cooperative banks, and urban cooperative banks. The RBI also released four separate circulars upon announcing the single cut to the SLR.

Scheduled commercial banks held approximately 90% of the banking system’s assets in 2009 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Makeup of Indian Banking System by Institution Type, 2009

Note: Total does not include the four unscheduled banks operating in India in 2009.

Source: RBI 2009h; RBI 2010b; author’s calculations.

The RBI did not issue circulars cutting the CRR for nonscheduled banks. Their CRR was fixed by statute at 3% of NDTL during the crisis period (Banking Regulation Act 1949, Sec. 18; RBI 2008a).

Timing

1

The RBI began raising the CRR in fall 2004 to sterilize liquidity impacts of large foreign exchange purchases and to contain domestic inflationary pressures (RBI 2008w; RBI 2009g).

The central bank cut the CRR four times between October 2008 and January 2009 to alleviate the sharp liquidity contraction that the GFC triggered.FOctober 6–7, 2008, CRR cut circulars: RBI 2008c; RBI 2008d; RBI 2008e; RBI 2008f. October 10 CRR cut circulars: RBI 2008h; RBI 2008i; RBI 2008g; RBI 2008j. October 15–16 CRR cut circulars: RBI 2008k; RBI 2008l; RBI 2008m; RBI 2008n. November 3 CRR cut circulars: RBI 2008p; RBI 2008q; RBI 2008r; RBI 2008s. January 2 and 5, 2009, CRR cut circulars: RBI 2009a; RBI 2009b; RBI 2009c; RBI 2009d. Note: The October 10, 2008, circulars revised the initial October 6–7 CRR cuts to 150-bp cuts from 50-bp cuts. The cuts ultimately brought the rate down 400 bps, from 9% to 5% (RBI 2009g).

On September 16, 2008, the RBI announced that banks in need of liquidity could temporarily pledge up to 1.0% of their SLR-eligible NDTL to the LAF (RBI 2008b).FBanks could also seek a waiver for the penal interest rate that normally applied, but it is unclear how many banks, if any, sought or received this waiver (RBI 2008b) On November 3, the RBI formally reduced the SLR by 100 bps, from 25% to 24% (RBI 2008t).

The RBI began cutting its repo rate days after its first CRR cut. The central bank eventually reduced the repo rate 425 bps, from 9% to 4.75%. To keep banks from leaving funds with the RBI overnight, the central bank started cutting its reverse repo rate in December 2008, eventually bringing the rate to 3.25% from 6%.

While the RBI brought down its key policy rates, it also implemented a host of liquidity programs, as discussed in Key Design Decision No. 2, Part of Package (RBI 2009g). The RBI’s measures collectively released USD 87.5 billion into its financial system in the 2008–2009 fiscal year. See Figure 2.

Changes in Reserve Requirements

1

The RBI ultimately reduced the CRR by 400 bps over the course of five successive rate cuts, bringing the measure from 9% to 5%. The RBI cut the SLR once, from 25% to 24%.

The RBI announced the first CRR cut of 50 bps, from 9.0% to 8.5%, on October 6, 2008. On October 10, it announced this cut would be increased to 150 bps, effective the following day (RBI 2008c; RBI 2008h). On October 15, the RBI announced an additional 100-bp cut, effective retroactively to the fortnight beginning October 11, bringing the CRR down to 6.5% (RBI 2008k). On November 3, the RBI announced two further reductions to the CRR, the first, of 50 bps, effective retroactively to the fortnight beginning October 25, and the second, also 50 bps, effective November 8 (RBI 2008p). Also on November 3, the RBI announced the 100-bp cut to the SLR to 24%, effective November 8 (RBI 2008t). See Figure 4 for a summary of GFC-era cuts to both reserve requirements.

Figure 4: Summary of Changes to Reserve Requirements

Note: The CRR cut announced on November 3, 2008, included two cuts: one effective retroactively to the fortnight beginning October 25 and one prospectively to the fortnight beginning November 8.

Sources: RBI 2008c; RBI 2008h; RBI 2008p; RBI 2008t; RBI 2009a.

Marginal Requirement

Although Section 42(1A) of the Reserve Bank of India Act gives the RBI the power to implement marginal RRs, the central bank did not do so during the GFC (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42[1A]; RBI 2006b; RBI 2008a).

Changes in Interest/Remuneration

1

The RBI stopped paying interest on cash reserves in 2006 after the Indian government amended the Reserve Bank of India Act to remove the practice (RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42(1A), n. 3).FPreviously, the RBI paid banks 3.5% on “eligible cash balances,” which were CRR balances above the previous statutory minimum of 3% and up to 5% (RBI 2006a).

As noted in Key Design Decision No. 7, Assets Qualifying as Reserves, scheduled banks could meet their SLR requirements with unencumbered government securities. However, real yields on short-term Indian government bonds were negative for the duration of the SLR cut.

Other Restrictions

1

If an institution failed to maintain at least 70% of its CRR requirement on a given day or failed to maintain its CRR or SLR average over the course of the RBI’s two-week calculation period, the central bank charged the institution a “penal interest” rate of 300 bps per annum above the prevailing bank rate on the amount by which the institution fell short on that day or two-week calculation period. If the shortfall continued for either the CRR or the SLR on the next succeeding day(s) or two-week period, the RBI charged a 500-bp penal interest rate above the bank rate (Banking Regulation Act 1949, Sec. 18; RBI 2006b; RBI 2008a; RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42).

If a bank continued to fail to meet the RBI’s CRR requirements (and was therefore subject to the penal interest rate of 500 bps per annum above the bank rate), the institution’s directors, managers, or secretaries who “knowingly” and “willfully” contributed to the breach were subject to fines (RBI 2008a, sec. 3.15[b]). The RBI could also prohibit the institution from accepting any new deposits (RBI 2008a; RBI Act 1934, Sec. 42).

Impact on Monetary Policy Transmission

1

In its press release announcing the first round of CRR cuts, RBI officials stated that “active liquidity management” was a key part of its monetary policy strategy (RBI 2008u). The CRR itself was the RBI’s key monetary policy tool (RBI 2014). By adjusting the CRR, the RBI could change both reserve money and the money multiplier (RBI 2009g).

In its 2008–2009 annual report, RBI officials said that at the beginning of the fiscal year, risk premiums, among other factors, had offset policy rate cuts and constrained monetary policy transmission. However, by the last quarter of the year, deposit and lending rates had started to moderate in response to the RBI’s rate cuts and liquidity policies, such as the CRR reductions (RBI 2009g).

By requiring banks to invest a portion of their liabilities in government securities, the RBI intended for the SLR to artificially suppress the cost of borrowing for the Indian government, thereby dampening the transmission of the RBI’s interest rate changes across the term structure (RBI 2014).

Duration

1

The RBI did not announce plans to begin raising the CRR when it made cuts to the ratio in late 2008 and early 2009. RBI officials described the cuts as temporary, noting that the central bank would review the ratio on an ongoing basis (RBI 2008u).

The RBI maintained the CRR at 5% from January 2009 to March 2010, when it hiked the CRR 75 bps to contain inflation and normalize policy following the GFC (RBI 2010a).

Initially, the RBI announced that the SLR would be relaxed temporarily, by allowing scheduled banks to pledge a portion of their SLR-eligible assets to the LAF, but a month and a half later, the RBI announced that the 100-bp reduction was effective until further notice. The SLR reverted to its pre-crisis level on October 28, 2009, roughly one year after the RBI cut it to 24% (RBI 2008b; RBI 2009e; RBI 2009g).

Key Program Documents

-

(Thorat 2009) Thorat, Usha. 2009. “Impact of Global Financial Crisis on Reserve Bank of India (RBI) as a National Regulator.” Presentation delivered at the 56th EXCOM Meeting and FinPower CEO Forum organized by APRACA. Seoul, South Korea.

Presentation by former Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank of India Usha Thorat detailing the Global Financial Crisis’ impact on the central bank and its various roles.

-

(RBI 2006a) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2006a. “Amendments to the Reserve Bank of India Act and Cash Reserve Ratio.” Press release No. 2005-2006/1668.

Reserve Bank of India press release announcing changes to cash reserve ratio policy.

-

(RBI 2006b) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2006b. “Master Circular - Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) and Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR), Chief Executives of All Scheduled Commercial Banks (Excluding Regional Rural Banks), RBI/2006-07/145.” Master Circular No. RBI/2006-07/ 145 | DBOD.No. Ret.BC. 34 /12.01.001/2006-07.

Reserve Bank of India October 2006 master circular outlining its instructions for adhearing to the RBI’s cash reserve ratio and statutory liquidity ratio rules.

-

(RBI 2008a) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008a. “Master Circular Maintenance of Statutory Reserves Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) and Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR), Chief Executive Officers of All Primary (Urban) Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-09/60.” Master Circular No. RBI/2008-09/60 | UBD CO Ret /MC No/ 15/12.03.000/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India July 2008 master circular outlining its instructions for adhearing to the RBI’s cash reserve ratio and statutory liquidity ratio rules.

-

(RBI 2008b) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008b. “RBI Announces Market Measures, 2008-2009/338.” Circular.

Initial announcement of RBI’s response to the GFC.

-

(RBI 2008c) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008c. “CRR Reduced, All Scheduled Commercial Banks (Excluding Regional Rural Banks), RBI/2008-2009/203.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/203 | Ref: DBOD.No.Ret.BC. 52/12.01.001/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular announcing the first in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for certain scheduled commercial banks.

-

(RBI 2008d) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008d. “RRBs – CRR Reduced, All Regional Rural Banks, RBI/2008-2009/205.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/205 | RPCD.CO.RRB. No. BC.40/ 03.05.28(B)/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular announcing the first in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for regional rural banks.

-

(RBI 2008e) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008e. “Scheduled Primary (Urban) Co-Operative Banks - CRR Reduced, The Chief Executive Officers of All Scheduled Primary (Urban) Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/206.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/206 | Ref: UBD (PCB).No./4/12.03.000/2008-09. Mumbai: Reserve Bank of India.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular announcing the first in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled urban cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2008f) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008f. “Scheduled State Co-Operative Banks – CRR Reduced, All Scheduled State Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/204.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/204 | RPCD.CO.RF.BC.No. 39/07.02.01/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular announcing the first in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled state cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2008g) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008g. “All Scheduled State Co-Operative Banks – CRR Reduced, All Scheduled State Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/212.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/212 RPCD.CO.RF.BC.No. 43/07.02.01/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular revising a previously announced cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled state cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2008h) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008h. “CRR Reduced, All Scheduled Commercial Banks (Excluding Regional Rural Banks), RBI/2008-2009/214.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/214 | Ref: DBOD.No.Ret.BC.55/12.01.001/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular revising a previously announced cash reserve ratio cuts for certain scheduled commercial banks.

-

(RBI 2008i) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008i. “RRBs – CRR Reduced, All Regional Rural Banks, RBI/2008-2009/213.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/213 | RPCD.CO.RRB. No. BC.44/ 03.05.28(B)/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular revising a previously announced cash reserve ratio cuts for regional rural banks.

-

(RBI 2008j) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008j. “Scheduled Primary (Urban) Co-Operative Banks – CRR Reduced, The Chief Executive Officers of All Scheduled Primary (Urban) Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/216.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/216 | Ref: UBD (PCB).No./5 /12.03.000/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular revising a previously announced cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled urban cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2008k) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008k. “CRR Reduced - Scheduled Commercial Banks, All Scheduled Commercial Banks (Excluding Regional Rural Banks), RBI/2008-2009/228.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/228 | Ref: DBOD.No.Ret.BC.61/12.01.001/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular announcing the second in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for certain scheduled commercial banks.

-

(RBI 2008l) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008l. “RRBs – Reduction in CRR, All Regional Rural Banks, RBI/2008-2009/234.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/234 | RPCD.CO.RRB. No. BC.46/ 03.05.28(B)/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular announcing the second in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for regional rural banks.

-

(RBI 2008m) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008m. “Scheduled StCBs – Reduction in CRR, All Scheduled State Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/231.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/231 | RPCD.CO.RF.BC.No. 48/07.02.01/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular announcing the second in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled state cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2008n) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008n. “Maintenance of Cash Reserve Ratio - Urban Co-Operative Banks, The Chief Executive Officers of All Scheduled Primary (Urban) Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/239.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/239 | Ref: UBD (PCB).No./7 /12.03.000/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 circular announcing the second in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled urban cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2008o) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008o. “RBI Announces Further Measures for Monetary and Liquidity Management.” Circular.

RBI announcement of additional RR cuts.

-

(RBI 2008p) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008p. “CRR Reduced, All Scheduled Commercial Banks (Excluding Regional Rural Banks), RBI/2008-2009/254.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/254 | Ref: DBOD.No.Ret.BC.71/12.01.001/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India November 2008 circular announcing the third in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for certain scheduled commercial banks.

-

(RBI 2008q) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008q. “RRBs – CRR Reduced, RBI/2008-2009/264.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/264 | RPCD.CO.RRB.BC.No.59/ 03.05.28(B)/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India November 2008 circular announcing the third in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for regional rural banks.

-

(RBI 2008r) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008r. “Scheduled StCBs – CRR Reduced, All Scheduled State Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/259.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/259 | RPCD.CO.RF.BC.No. 57/07.02.01/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India November 2008 circular announcing the third in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled state cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2008s) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008s. “Scheduled UCBs – CRR Reduced, The Chief Executive Officers of All Scheduled Primary (Urban) Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/265.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/265 | Ref: UBD (PCB).No./8 /12.03.000/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India November 2008 circular announcing the third in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled urban cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2008t) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008t. “SLR Reduced, 2008–2009/ 255.” Circular.

RBI announcement of 100bps SLR reduction.

-

(RBI 2009a) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2009a. “CRR Reduced, All Scheduled Commercial Banks (Excluding Regional Rural Banks), RBI/2008-2009/339.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/339 | Ref: DBOD.No.Ret.BC.103 /12.01.001/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India January 2009 circular announcing the final cut in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for certain scheduled commercial banks.

-

(RBI 2009b) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2009b. “RRBs – CRR Reduced, All Regional Rural Banks, RBI/2008-2009/345.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/345 | RPCD.CO.RRB.BC.No.82/ 03.05.28(B)/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India January 2009 circular announcing the final cut in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for regional rural banks.

-

(RBI 2009c) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2009c. “StCBs – CRR Reduced, All Scheduled State Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/344.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/344 | RPCD.CO.RF.BC.No.81/07.02.01/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India January 2009 circular announcing the final cut in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled state cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2009d) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2009d. “UCBs – CRR Reduced, The Chief Executive Officers of All Scheduled Primary (Urban) Co-Operative Banks, RBI/2008-2009/346.” Circular No. RBI/2008-2009/346 | Ref: UBD (PCB).No./9 /12.03.000/2008-09.

Reserve Bank of India January 2009 circular announcing the final cut in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts for scheduled urban cooperative banks.

-

(RBI 2009e) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2009e. “SLR Increased, 2009-2010/195.” Circular.

RBI announcement of SLR hike back to pre-crisis levels, roughly one year after the 100 bps cut.

-

(Banking Regulation Act 1949) Parliament of India (Banking Regulation Act). 1949. “The Banking Regulation Act of 1949, Amended as of 2021.” Act, Amended as of 2021.

Indian act creating the country’s regulatory framework.

-

(Banking Regulation Act Amendment 2007) Parliament of India (Banking Regulation Act Amendment). 2007. “Banking Regulation (Amendment) Act, 2007.” Act, Amended as of 2007.

Indian act amending the Banking Regulation Act governing the use of the SLR.

-

(Cabinet Secretariat 1961) Cabinet Secretariat. 1961. “The Government of India (Transaction of Business Rules) Rules, 1961, Amended as of 2020.” Rules.

Cabinet Secretariat rules detailing the cabinet’s policies.

-

(RBI Act 1934) Parliament of India (RBI Act). 1934. “Reserve Bank of India Act of 1934, Amended as of 2019.” Act, Amended as of 2019.

Indian act establishing the Reserve Bank of India and outlining its powers.

-

(Bandyopadhyay 2008) Bandyopadhyay, Tamal. 2008. “Liquidity Crisis: Where Has All the Money Gone?” Mint, October 13, 2008, sec. BP.

News article discussing CRR cuts.

-

(Dhasmana 2009) Dhasmana, Indivjal. 2009. “Bank Funds Not Reaching Industry, Consumers: Nath.” News Article. Press Trust of India.

Press Trust of India article detailing former Commerce and Industry Minister Kamal Nath’s comments about inadequate lending in the broader Indian economy.

-

(Hindu Business Line 2008) Hindu Business Line. 2008. “RBI in a Dilemma over SLR.”

News article describing the complications in reducing the SLR.

-

(Reuters News 2008) Reuters News. 2008. “Indian Bond Yields Rise, More Policy Measures Eyed.” Reuters News, October 13, 2008.

Reuters report on the potential for CRR and SLR cuts.

-

(Sahu 2008) Sahu, Prashant K. 2008. “Govt, RBI Set to Ease Liquidity.” Business Standard, October 14, 2008.

Article citing the RBI Chairman’s statements on the first two CRR cuts.

-

(Reuters News Staff 2009) Reuters News Staff. 2009. “Indian Cash Rates Ease on Ample Funds with Banks.” News Article.

Reuters article detailing cash rates moves in late January 2009.

-

(Roy and Bhoir 2009) Roy, Anup, and Anita Bhoir. 2009. “Firms Say Banks Not Disbursing Loans; Lenders Claim Poor Demand.” News Article. Mint.

Mint article detailing Indian business concerns about lending.

-

(Tarapore 2009) Tarapore, S. S. 2009. “Well-Modulated Monetary Policy.” News Article. The Hindu Business Line.

The Hindu Business line opinion article detailing the Reserve Bank of India’s decision to slow its monetary policy loosening.

-

(RBI 2008u) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008u. “RBI Reduces CRR for Liquidity Management.” Press release No. 2008-2009/447.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 press release announcing the first in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts.

-

(RBI 2008v) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008v. “RBI Announces Reduction in CRR for Liquidity Management.” Press release No. 2008-2009/467. Mumbai.

Reserve Bank of India October 2008 press release announcing the first in a series of four cash reserve ratio cuts.

-

(RBI 2009f) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2009f. “Issuance of Government of India Cash Management Bills.” Press release No. 2009–2010/227.

RBI document on the issuance of cash management bills by the Indian government.

-

(RBI 2021) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2021. “Inclusion in/Exclusion from the Second Schedule to the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 - Regional Rural Banks (RRBs), RBI/2021-22/133.” Circular No. RBI/2021-22/133 | DOR.Rur.REC.70/31.04.002/2021-22.

Reserve Bank of India November 2021 circular announcing the inclusion and removal of certain banks from its Second Schedule.

-

(IMF 2009) International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2009. “India: 2008 Article IV Consultation—Staff Report; Staff Statement; Public Information Notice on the Executive Board Discussion; and Statement by the Executive Director for India.” IMF Country Report No. 09/187. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

IMF report examining India’s economy.

-

(Kumar and Vashisht 2012) Kumar, Rajiv, and Pankaj Vashisht. 2012. “The Global Economic Crisis: Impact on India and Policy Responses.” Chapter in The Global Financial Crisis and Asia: Implications and Challenges, Edited by Masahiro Kawai, Mario B. Lamberte, and Yung Chul Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book chapter analyzing the GFC’s impact on India and how policymakers responded to the crisis.

-

(RBI 2007) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2007. “Report of The Working Group on Preparing Guidelines for Access to Payment Systems.” Reserve Bank of India Central Office.

Reserve Bank of India paper proposing guidelines for minimum eligibility criteria to become members of the clearing houses/payment systems.

-

(RBI 2008w) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2008w. “Reserve Bank of India Annual Report, 2007-2008.” Annual Report.

Reserve Bank of India annual report for the year ended June 30, 2008.

-

(RBI 2009g) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2009g. “Reserve Bank of India Annual Report, 2008-2009.” Annual Report.

Reserve Bank of India annual report for the year ended June 30, 2009.

-

(RBI 2009h) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2009h. “Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India 2008-09.”

Reserve Bank of India report documenting banking trends in 2008-2009.

-

(RBI 2010a) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2010a. “Reserve Bank of India Annual Report, 2009-2010.” Annual Report.

Reserve Bank of India annual report for the year ended June 30, 2010.

-

(RBI 2010b) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2010b. “Report on Trend and Progress of Banking in India 2009-10.”

Reserve Bank of India report documenting banking trends in 2009-2010.

-

(RBI 2014) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2014. “Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework.” Expert Committee Report.

Reserve Bank of India report detailing efforts to revise the central bank’s operating framework.

-

(RBI 2017) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2017. “Reserve Bank of India Annual Report, 2016-2017.” Annual Report.

Reserve Bank of India annual report for the year ended June 30, 2017.

-

(RBI 2020) Reserve Bank of India (RBI). 2020. “Functions and Working of RBI.”

Reserve Bank of India report detailing how and why the central bank works.

-

(Sanghvi, Patnaik, and MG 2021) Sanghvi, Khyati, Pratik Patnaik, and Vineetha MG. 2021. “A General Introduction to the Banking Regulatory Regime in India.” Article. Lexology.

Lexology article detailing the Indian bank regulatory regime.

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Reserve Requirements

Countries and Regions:

- India

Crises:

- Global Financial Crisis