Market Support Programs

Eurozone: Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program

Purpose

“address the risk of market fragmentation [in bond markets,] impairment to monetary policy transmission [and] ease the monetary policy stance in light of the contraction that resulted from COVID-19” (Lagarde 2020b, 4)

Key Terms

-

Launch DatesAnnounced: March 18, 2020

-

Launch DatesAnnounced: March 18, 2020

-

Operational DateMarch 26, 2020

-

Wind-down DatesProjected March 2022

-

Legal AuthorityStatute of ESCB, article 18.1; Decision 2020/440 of the ECB

-

Source(s) of FundingCreated reserves

-

Overall SizeEUR 1.85 trillion

-

Eligible Collateral (or Purchased Assets)Public-sector securities issued by governments and international financial institutions based in the eurozone: covered bonds, corporate debt, commercial paper, asset-backed securities, all in the secondary market with remaining maturities of between 70 days and 31 years

-

Notable FeaturesEUR 1.65 trillion on February 4, 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic quickly engulfed the European Union’s economy in 2020. As investors sought safe assets, marketable debt yields rose dramatically. To lower the cost of borrowing, the European Central Bank (ECB), alongside the 19 national central banks (NCBs) that comprise the Eurosystem, purchased marketable debt in secondary markets. Asset eligibility mirrored that of the ECB’s Asset Purchase Program (APP), an ongoing quantitative easing program which the ECB expanded during the pandemic. The main difference was that the PEPP allowed debt issued by Greece, which did not have an investment-grade credit rating. The rate that the PEPP purchased securities within each asset class could also vary, unlike the APP. When the ECB announced the PEPP on March 27, 2020, it approved EUR 750 billion (USD 825 billion) in total purchases to wind down no later than December 2020. The ECB expanded the program twice to allow EUR 1.85 trillion in asset purchases through March 2022. As of February 2022, the ECB and NCBs had purchased a total of EUR 1.6 trillion in assets through the program. The PEPP’s effects in the months after the pandemic outbreak were difficult to disentangle from the concurrent APP except that the ECB was able to close yield spreads between German and Greek debt. Debt yields stabilized shortly after the PEPP’s establishment and the APP’s expansion.

The spread of COVID-19, and public health measures designed to contain it, shattered market confidence in March 2020. Investors sought riskless assets, pushing up yields as liquidity evaporated throughout the financial system (Lane 2020a).

On March 18, 2020, the ECB responded by unveiling the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) (ECB 2020e). Under the PEPP, the ECB and 19 national central banks (NCBs; collectively, the EurosystemFIn 2020, the 19 Eurosystem members were Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain.) purchased securities issued in the eurozone or secured by eurozone assets and held them to maturity. It followed the structure and eligibility criteria of the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme (APP), which coordinated four subsidiary programs: the Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP); the Public Sector Securities Purchase Programme (PSPP); the Asset-Backed Securities Purchase Programme (ABSPP); and the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP) (ECB 2021b). The APP was created to conduct quantitative easing as the Euro Crisis threatened deflation in the eurozone (ECB/2020/9 2020, preamble, para. 6). Then, the purpose of the APP was to anchor asset prices and sustain the markets (Blot, Creel, and Hubert 2020, 11). In each program, the 19 NCBs joined the ECB in purchasing securities (ECB 2021b). Additionally, Each NCB purchased the sovereign debt of its member state.

The first component of the APP, the CBPP, began in 2009; since 2014, CBPP3 had purchased covered bonds and multi cédulas (ECB/2020/8 2020, art. 3.3) (See Smith [2020a] for a review of CBPP1 and CBPP2). Later in 2014, central banks began purchasing asset-backed securities under the ABSPP (ECB/2014/45 2015, art. 1). Early 2015 saw the introduction of the PSPP, which bought sovereign debt issued by governments and international financial institutions based in the eurozone (ECB/2020/9 2020). Last, the CSPP bought investment-grade debt issued by entities not eligible under the other programs beginning in 2016 (ECB/2016/16 2016). Each program’s timeline is shown in Figure 1. The Securities Markets Programme (SMP) purchased bonds from the governments of the eurozone’s weakest economies; the SMP concluded before the APP’s current subsidiary programs had begun (Benigno et al. 2020, 7; see Smith 2020b).

Figure 1: Phase-in and -out of ECB asset purchase programs

Source: ECB 2021b.

Source: ECB 2021b.

These programs, except the ABSPP, continued to purchase their holdings of securities throughout the COVID-19 pandemic (ECB 2020a). When COVID-19 struck, the Governing Council of the ECB—composed of the heads of the ECB and NCBs (European Union 1992, art. 14)—opted to create a new program instead of extending and enlarging the APP. Though the PEPP purchased virtually the same assets as the APP, it gave the Eurosystem more flexibility in allocating funds and a wider range of maturities it could purchase. The ability to tweak the PEPP’s portfolio was important because the COVID-19 crisis brought more uncertainty than did the period following the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) (Blot, Creel, and Hubert 2020, 6). As COVID-19 first spread in March 2020, the ECB was not confident it knew what risks lay ahead. Officials worried that the pandemic would affect each country’s health system and economy differently and create further financial turbulence (Lane 2020a). This worry contrasted with policymakers’ preoccupation with disinflation across the eurozone following the GFC. Both programs served the ECB’s price-stability mandate, but they fought price-stability threats from different directions.

Assets eligible for the PEPP expanded upon the APP in two key ways. First, the PEPP could purchase debt issued or guaranteed by Greece even if Greece’s credit rating was below the PEPP’s standards for public-sector securities. In the period that followed, the spread between Greek and German yields fell to its lowest level since 2008, before Greece faced the sovereign debt and eurozone crises (OECD 2007–2021). Second, the PEPP could purchase securities with remaining maturities as short as 70 days—28 days for commercial paper—and up to six months. This widened the pool of securities eligible for purchase beyond that of the APP, though its effects have not been well studied. The remaining eligibility criteria were unchanged from those of the APP (ECB, n.d.).

The PEPP required enormous resources to accomplish such goals. Its announcement carried a EUR 750 billion (USD 825 billion)FUSD 1 = EUR 0.91 during March 2020. authority, but, as the pandemic continued to harm economies, the Governing Council extended the timeframe for purchases and reinvestments and increased its overall authority, first to EUR 1.35 trillion and then to EUR 1.85 trillion (ECB 2020f; ECB 2021f). To avoid the sort of unexpected liquidity fluctuations the PEPP was meant to prevent, the Eurosystem purchased securities at a constant pace. As of February 2022, the Eurosystem had purchased EUR 1.65 trillion of PEPP securities (see Figure 2) (ECB 2020a). When the ECB expanded the PEPP’s size, it also extended its timeframe. From an initial end date in December 2020, the ECB settled on March 2022 for its final purchases, with dividends reinvested until end-2023 (ECB 2020e).

Figure 2: Liquidity Provided by the Eurosystem, 2020–2021

Source: ECB 2020a.

Source: ECB 2020a.

Literature on the PEPP continued to evolve as of October 2021. The waiver allowing Greek debt proved controversial and consequential. Politically, it risked legal challenges along the same lines as the objections lobbed at the PSPP since 2015 (Grund 2020, 2). Economically, it whittled Greek and German debt yields to pre-GFC spreads (Blot, Creel, and Hubert 2020, 14; OECD 2007–2021).

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

1

The press release announcing the PEPP cited “the serious risks to the monetary policy transmission and the outlook for the euro area posed by the outbreak and escalating diffusion of the coronavirus” (ECB 2020e). With the PEPP, the ECB gave itself the ability to purchase Greek sovereign debt and assets at very short and long maturities. PEPP purchases of a country’s sovereign debt could also exceed limits the ECB set in the Eurosystem “capital key.” This flexibility was absent in the APP and was the reason the PEPP was created.

Flexibility was required because of the uncertainty caused by COVID-19 and because of differences in eurozone economies that the APP was not equipped to address. Researchers had warned about market fragmentation—in which credit access diverged across eurozone countries, increasing spreads between fundamentally similar assets and threatening the transmission of ECB monetary policy—several years before the PEPP’s announcement (Berenberg-Gossler et al. 2016, 11). ECB President Christine Lagarde (2020a, 9; 2020b, 4; 2020c, 4) said that COVID-19 caused worries over fragmentation to spread. The PEPP could respond to fragmentation in particular markets by varying purchases across maturities and asset classes. The program could also target differences between eurozone economies by purchasing relatively more or less of a country’s debt.

As shown in Figure 3, investors fled the assets of weaker eurozone economies in favor of stronger ones as COVID-19 erupted. Investors’ flight-to-safety during a crisis like the pandemic has a “geographic dimension” because the European monetary union lacked a common safe asset (Lane 2020a). Yields on lower-rated eurozone sovereigns, such as Greece, ticked up as a result, while yields on higher-rated eurozone sovereigns, such as Germany, remained stable.

The PEPP’s general strategy as a large-scale asset purchase program relied on the theory that yields would fall if all else were held equal, and that this demand would spill over into other markets, lowering yields across markets (Benigno et al. 2020, 11–13). The PEPP also made securities available for lending, allowing the Eurosystem to create a market in securities if private markets suffered dislocations (ECB 2021e; ECB/2020/17 2020, art. 7). Both of these features were shared with the APP. However, the goals of the PEPP and APP were different. While the ECB set up the APP to conduct quantitative easing and fight persistent deflationary forecasts for the eurozone, it set up the PEPP to address the risk of fire sales as investors rushed to sell assets during a calamitous moment, according to a member of the ECB’s Executive Board (Blot, Creel, and Hubert 2020, 11; Lane 2020a).

Figure 3: Ten-year Government Bond Spreads for Eurozone Countries, Monthly Data

Source: OECD 2007–2021.

Source: OECD 2007–2021.

Part of a Package

1

In March 2020, the ECB also announced that it would expand the APP in light of the pandemic, making non-financial commercial paper eligible for purchase (Lane 2020b, 2). Outside of market liquidity programs, the ECB reactivated currency swap lines with the Federal Reserve, which were a key piece of its response to the Global Financial Crisis (Runkel, forthcoming b). And the ECB expanded other lending programs such as its open-market operations and Targeted Longer Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs).

Legal Authority

1

Decision 2020/440 of the ECB established the PEPP on March 26, 2020 (ECB/2020/17 2020, art. 8). The preamble of this decision outlined the reasons the Governing Council established the PEPP as well as the reasons for the waiver for Greek debt. The decision was short and relied heavily on terms and procedures defined in decisions that authorized the subprograms of the APP:

- ECB/2020/9 refining the terms and eligibility of the PSPP;

- ECB/2016/16 establishing the CSPP;

- ECB/2020/8 refining the terms and eligibility of the CBPP3;

- ECB/2014/45 establishing the ABSPP.

The purchases described in the PEPP decision were consistent with the ECB’s authority under the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank (Statute of the ESCB). Specifically, the ECB and national central banks could:

"operate in the financial markets by buying and selling outright (spot and forward) or under repurchase agreement and by lending or borrowing claims and marketable instruments, whether in Community or in non-Community currencies, as well as precious metals." (European Union 1992, sec. 18.1)

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union let the Governing Council issue this decision (TFEU [1957] 2012, vol. 326/1, sec. 132[2]). The power to issue decisions without further approval became important as the ECB expanded the PEPP’s size.

The PEPP decision interacted with several EU treaties, specifically those prohibiting the ECB from engaging in monetary financing.FThe Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ([1957] 2012, art. 123[2]) defined monetary financing as a “credit facility . . . in favour of . . . central governments, regional, local or other public authorities, other bodies as governed by public law, or . . . the purchase directly from them . . . of debt instruments.” As of August 2021, no challenges to the PEPP had been referred to EU courts, but active casesFThese claims were not trivial matters because of legal challenges brought earlier against the Outright Monetary Transactions and the PSPP (Gauweiler and Others v. Deutscher Bundestag 2015; Weiss and Others v. ECB 2018). In these cases, which eventually made their way to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), plaintiffs argued that the program in question either exceeded the ECB’s price-stability mandate, its ability to execute that mandate, or its prohibition on monetary financing (Grund 2020, 3–5). And, in each, German courts referred the cases to the CJEU, which had sole authority to interpret “legal acts by EU institutions based on EU law” (Grund 2020, 2). Grund (2020, 2) interpreted CJEU rulings to say that the programs were legal under EU law so long as the programs remained compliant with the ECB’s mandate, proportionate to the objectives, and compatible with the prohibition of monetary financing. against the PSPP would likely impact the PEPP as well given that the PEPP relied on the PSPP to define eligible securities.

Governance

1

The decision that created the PEPP was passed by the Governing Council of the ECB, which consisted of the governor of each NCB and the six-member ECB Executive Board: the President, Vice-President, and four other membersFIn 2020, the President was Christine Lagarde, the Vice President was Luis de Guindos, and the four other members were Philip R. Lane, Isabel Schnabel, Fabio Panetta, and Frank Elderson. (European Union 1992, secs. 10–11).

The decision establishing the PEPP required the ECB to publish the aggregate book value every week, the net and cumulative net purchases each month, and the book value of securities held each week (ECB/2020/17 2020, art. 6).

Administration

1

The Governing Council delegated authority to the Executive Board to “set the appropriate pace and composition of PEPP monthly purchases” (ECB/2020/17 2020, art. 5). The Executive Board could choose from which asset classes and countries the PEPP purchased. All EurosystemFIn 2020, the Eurosystem included the central banks of Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. The countries with representation in the Eurosystem are referred to as the euro area (EA) or eurozone. central banks purchased PEPP securities—including public-sector securities of their respective member states—and no documents indicate that central banks employed outside firms to evaluate assets.

Communication

1

Before the PEPP was announced, ECB President Christine Lagarde (2020) said that the Governing Council was “not here to close spreads.” Yields on eurozone debt spiked after the comment, with the lowest-rated eurozone sovereigns seeing the largest spikes in volatility and yield (Reuters 2020; OECD 2007–2021). Lagarde walked back the point later, saying that the central bank was “fully committed to [avoiding] any fragmentation” (Reuters 2020). A report to the European Parliament stated that it was “reasonable to think that the implementation of this program was, if not due to, at least brought forward because of President Lagarde’s comment” (Blot, Creel, and Hubert 2020, 13). Markets also appeared to react to the announcement of the PEPP, as the volatility of sovereign debt—shown in Figure 4—fell for many eurozone bonds (Blot, Creel, and Hubert 2020, 13). The ECB’s initial announcements consisted of press releases, its decisions in the Official Journal of the European Union, and press conferences to explain the terms of the PEPP and its purpose.

Other PEPP communications did not appear to cause explosive effects on markets. ECB Executive Board members explained the PEPP in virtual speeches and in the ECB’s blog (Schnabel 2021; Lane 2020a). These platforms also allowed policymakers to describe the program’s activities.

Figure 4: Sovereign-Debt Volatility and Eurozone Developments

Source: Blot, Creel, and Hubert 2020, 13.

Source: Blot, Creel, and Hubert 2020, 13.

Disclosure

1

The decision establishing the PEPP required the ECB to publish the aggregate book value every week, the net and cumulative net purchases each month, and the book value of securities held each week (ECB/2020/17 2020, art. 6). The ECB exceeded those requirements by publishing every other month holdings by asset class and, for the PSPP, holdings by issuer (ECB 2020b). These disclosures were not required by the ECB decision creating the PEPP or by any legislation.

SPV Involvement

1

The PEPP did not use an SPV to administer its purchases.

Program Size

1

The ECB’s original decision authorized EUR 750 billion for PEPP (ECB/2020/17 2020, art. 1). After it became clear that the pandemic would continue to harm European economies, inflation projections fell (ECB 2021f). In June 2020, the ECB (ECB 2020f) expanded PEPP to EUR 1.35 trillion to boost the effects of its accommodative monetary policy. In March 2021, the ECB expanded PEPP to EUR 1.85 trillion and committed to speeding up purchases (ECB 2021f). In implementing this policy, NCBs bought securities gradually rather than all at once. Prior APP procedures suggest that “Eurosystem staff regularly assessed bond market liquidity indicators” to avoid distortionary effects of such large purchases (Hammermann et al. 2019, sec. 3).

As of February 2022, PEPP has purchased eligible assets worth EUR 1.6 trillion (ECB 2020a). The Executive Board mostly purchased public-sector securities, some commercial paper and corporate bonds, but very few covered bonds, and no asset-backed securities, as shown in Figure 5 (ECB 2020b).

Figure 5: PEPP Purchases by Asset Class

Source: ECB 2020b.

Source: ECB 2020b.

Source(s) of Funding

1

The Eurosystem funded asset purchases by expanding their central bank balance sheets. When a central bank purchased securities under the APP, that central bank credited the reserve account of the bank connected to that particular security; following Decision 2020/440, the same applied to PEPP purchases (ECB 2017, 64).FThe Eurosystem used banks’ reserve accounts as settlement services for PEPP transactions even if the seller of a security was not a bank with a Eurosystem reserve account holder. In such a case, the central bank would credit a bank at which the seller held an account (ECB 2017, 64). In such a way, a bank could be connected to a security without selling it. The ECB only purchased 10% of public-sector securities that were purchased under the program; NCBs purchased the remainder of the debt of their respective member state (ECB/2020/9 2020, art. 6).

The Governing Council committed Eurosystem central banks to reinvest the principal from maturing PEPP securities (ECB 2021f). The Eurosystem shared all risks of private-sector-securities defaults, and 20% of public-sector-securities defaults (ECB, n.d.). This meant that if these securities bore losses, all losses of private-sector securities would be divided among the Eurosystem central banks according to the Eurosystem capital key, while only losses from 20% of public-sector purchases would be divided.

Eligible Institutions

1

Eligibility criteria for PEPP counterparties were set by earlier decisions establishing the APP and its component programs. All programs could transact with institutions eligible for monetary policy operations and investment managers entrusted with Eurosystem central bank portfolios (ECB/2014/45 2015, art. 4; ECB/2016/16 2016, art. 6; ECB/2020/8 2020, art. 4; ECB/2020/9 2020, art. 7). The Governing Council could also designate other entities for outright transactions under the ABSPP after the ECB conducted a counterparty-risk assessment (ECB/2014/45 2015, art. 4). Institutions were eligible for monetary policy operations if they were subject to reserve requirements, were financially sound, were subject to supervision by an EU or European Economic Area authority, and if they fulfilled any requirements unique to the NCB with which they sought to transact (ECB 2006, chap. 2.1).

In all, Eurosystem central banks sought a large number of counterparties (the APP had used more than 350; Hammermann et al. 2019, sec. 3). Avdjiev, Everett, and Shin (2019, 69) reported that investors outside the eurozone, and largely in the United Kingdom, were responsible for half of APP sales. Spreading purchases over time reduced distortions on bond-market segments and made it easier to reach hard-to-reach market segments (Hammermann et al. 2019, sec. 3).

Auction or Standing Facility

1

National central banks seemed to follow their existing asset-purchase procedures for implementing the PEPP (ECB/2020/17 2020, preamble). The majority of APP purchases saw sellers access a standing facility at their designated NCB.FA country’s designated NCB was not always the NCB based in it. Designated NCBs varied for corporate debt and asset-backed securities, as shown in Figure 7. NCBs purchased public-sector securities and covered bonds for their home country. These facilities engaged in bilateral trades, whereby the NCB took the best price quoted by its counterparties in phone calls and over electronic trading platforms. Bilateral trading allowed NCBs to handle the “liquidity and heterogeneity” of the various eurozone jurisdictions (Hammermann et al. 2019, box 1).

Banque de France, De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB), and Lietuvos Bankas first trialed reverse auctions for the PSPP in 2015 alongside their standing facilities (Hammermann et al. 2019, box 1). In 2016, the Central Bank of Malta began conducting reverse auctions of public-sector securities (ECB 2021a). The Eurosystem endorsed their usage in illiquid bond markets, where bilateral trading risked mispricing assets.

DNB explained its auction process in detail on its website. It conducted variable-rate reverse auctions for Dutch securities issued on the secondary market. It announced auctions via Bloomberg two days before an operation. In an announcement, it listed which securities were eligible for the upcoming auction and offered the option to transact bilaterally with dealers for securities not specified by the DNB. During auctions, each counterparty had 20 minutes to submit via Bloomberg up to five pairs of amounts and prices per the security’s ISIN, a unique identifier. DNB allocated purchases by ranking offers against “a theoretical yield curve.” Settlement occurred two days after (DNB 2020).

Loan or Purchase

1

Implementation of the PEPP was decentralized and followed existing APP procedures (ECB/2020/17 2020, preamble). This meant that the ECB and each of the 19 NCBs could use different systems and processes to purchase eligible securities. However, per the APP frameworks, not every central bank purchased every security. The whole Eurosystem purchased public-sector securities, but only six NCBs purchased corporate debt, and only four purchased asset-backed securities. Per the CSPP, Nationale Bank van Belgie, Deutsche Bundesbank, Banco de España, Finlands Bank, Banque de France, and Banca d’Italia purchased corporate debt on behalf of the eurozone (ECB 2021d). Five of these six also purchased asset-backed securities—DNB substituted for Finlands Bank—as shown in Figure 6 (ECB 2021c).

Figure 6: Purchasing Jurisdictions for the CSPP and ABSPP

Note: Deutsche Bundesbank, Banco de España, and Banca d’Italia purchased securities from Dutch issuers but with, respectively, Germany, Spain, and Italy as the country of risk. Nationale Bank van Belgie purchased securities from Dutch issuers with any other country of risk.

Source: ECB 2021c; ECB 2021d.

The APP prohibition on purchasing newly issued public sector securities on the primary market also applied to the PEPP (ECB/2020/9 2020, art. 4; ECB/2016/16 2016, art. 1). These rules sought to ensure central banks did not engage in monetary financing, which was prohibited by the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ([1957] 2012, art. 123). The private-sector programs could purchase in both the primary and secondary market (Hammermann et al. 2019, box 1).

Eligible Collateral or Assets

2

Under the PEPP, the Eurosystem purchased securities eligible for the APP programs: CSPP, CBPP3, ABSPP, and PSPP (ECB/2020/17 2020, art. 1). The CSPP included commercial paper issued by non-financial corporations—a small but growing portion of the market—with maturities as short as 28 days (de Guindos and Schnabel 2020). All other PEPP securities required remaining maturities of at least 70 days and no longer than 30 years and 364 days, which was the same maximum remaining maturity as the PSPP and CSPP used (ECB/2020/17 2020, art.2; ECB/2020/9 2020, art. 3.3; ECB/2016/16 2016, art. 2.2). Previously, the CSPP had only accepted commercial paper with maturities as low as six months (de Guindos and Schnabel 2020). The ECB maintained that the halted issuance of commercial paper and the heightened yields of outstanding commercial paper motivated their decision to expand the eligibility to shorter term commercial paper in PEPP (de Guindos and Schnabel 2020). Previously, the PSPP accepted remaining maturities with as little as one year. Neither the ABSPP nor the CBPP3 specified minimum or maximum remaining maturities.

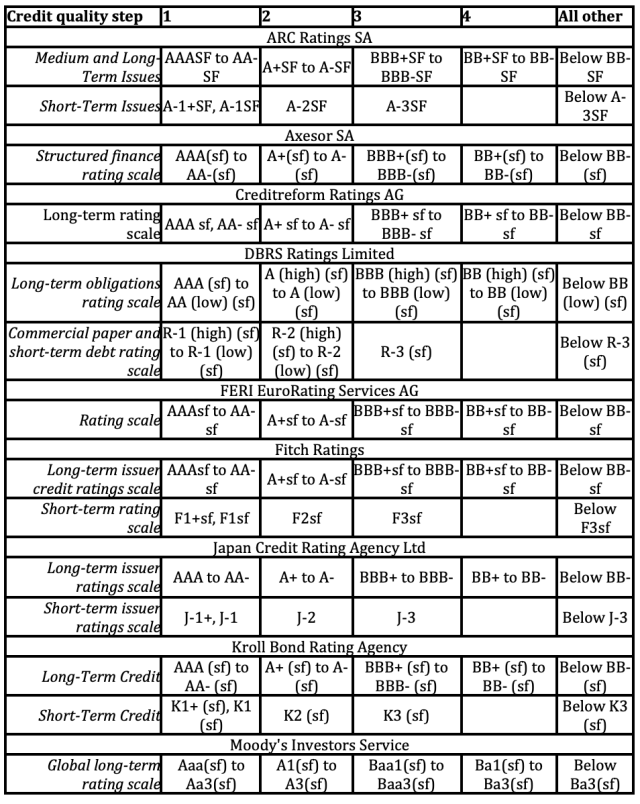

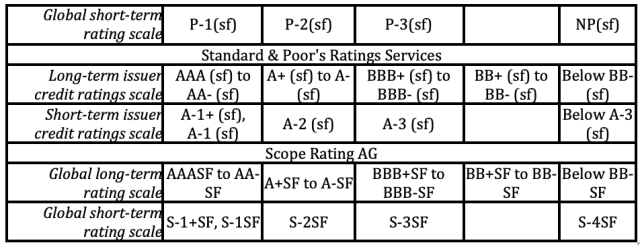

The ECB set eligibility criteria according to both issuer and asset class, as shown in Figure 7. The ECB established eligibility criteria to target issuers of covered bonds and asset-backed securities, and non-financial corporations. In the PSPP, the ECB accepted debt issued by eurozone nongovernmental organizations such as multilateral development banks and international financial institutions (ECB/2020/9 2020, art. 3[1]). This provision expanded the list of eligible issuers to include the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, Paris Club, and United Nations.

In addition, to be eligible for the CSPP, CBPP3, and ABSPP, securities must have been eligible as collateral in Eurosystem refinancing operationsFAll public-sector securities reaching Credit Quality Step 3 were eligible for monetary policy operations. (ECB 2021c; ECB 2021d; ECB 2020d). The Eurosystem refinancing eligibility requirements for collateral were generally the same, if not more relaxed, than those set out in the APP and PEPP legislation.

Figure 7: Eligibility Criteria for Assets

Note: i: External Credit Assessment Institutions, as defined by the ECB.

Note: i: External Credit Assessment Institutions, as defined by the ECB.

Sources: ECB/2014/45 2015; ECB/2016/16 2016; ECB/2020/8 2020; ECB/2020/9 2020, 039:188; ECB/2020/17 2020; ECB 2021d.

One clear difference from APP was that the PEPP also made sovereign debt from Greece eligible (ECB/2020/17 2020, art. 3). The establishing legislation said that, because the ECB had a better picture of Greece’s situation, it could more closely monitor conditions there for any negative effects on the rest of the eurozone. Greece had been subject to “enhanced surveillance” by the ECB due to domestic financial crises in the early 2010s (ECB/2020/17 2020, preamble). Controversy had surrounded Greek debt since 2010, when the country sought the first of three bailouts from international creditors, and its credit rating fell below Step 3 of the EU’s Credit Quality Scale (Greece Credit Ratings, n.d.; C/2016/6447 2016; see Appendix 1 for the full credit scale; see Runkel, forthcoming a).

In March 2020, Greek government bonds still did not meet the PSPP’s credit quality requirements; its long-term Fitch rating of BB lay in Credit Quality Step 4 (Fitch Ratings, n.d.). For this reason, the PSPP did not admit Greek debt (ECB/2020/9 2020, art. 3). But the ECB waived the credit-rating requirements for debt issued by Greece, citing the pandemic’s effects on Greek financial markets, knock-on effects of a Greek default, and the ECB’s ability to judge the situation due to its extraordinary involvement in the Greek economy (ECB/2020/17 2020). However, the decision may instead have had more to do with fears about the pandemic’s effects on Greece than with Greece’s effects on the eurozone. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the ECB had carved out similar exemptions allowing banks to post Greek debt as collateral in refinancing operations (see Runkel, forthcoming a).

Loan Amounts (or Purchase Price)

1

Following the ABSPP, the PEPP could not purchase more than 70% of a tranche of asset-backed securities, as marked by its International Securities Identification Number (ISIN) (ECB/2014/45 2015, art. 5). Following the CSPP, the PEPP could not purchase more than 70% of any ISIN for corporate bonds, not including public-sector corporate bonds (ECB/2016/16 2016, art. 4). Following the CBPP3, the PEPP could not purchase securities that—when pooled with CBPP1 and CBPP2 holdings—amounted to more than 70% of an ISIN (ECB/2020/8 2020, art. 3).

In the PSPP, ECB decisions restricted the amount of any one security that a national central bank could purchase to 33% of a single issue by a country subject to an economic adjustment program administered by the ECB, or 50% of a single issuance by a multilateral development bank or international financial institution. Moreover, purchases followed the ECB’s capital key, placing strict ratios on the amount that the Eurosystem could purchase of one member state’s debt relative to purchases of another member state’s debt (ECB/2020/9 2020, art. 6). These regulations limited the ECB’s ability to narrow spreads between sovereign debt issued by lower-rated countries and perpetually high-rated German debt.

The ECB lifted such limits in the PEPP (ECB/2020/17 2020, art. 4). The decision followed a spike in Greek debt yields after ECB president Christine Lagarde (2020) said, in response to a journalist’s question, that the Governing Council “are not here to close spreads,” which “is not the function or the mission of the ECB.”

Purchases of public-sector securities were guided—but not constrained—by the relative sizes of eurozone economies, codified in the Eurosystem capital key.FThis schedule listed the amount of ECB capital held by eurozone national central banks as a percentage of the total capital held by eurozone national central banks. It is easily confused with the ECB capital key, which listed the amount of ECB capital held by eurozone national central banks plus the amount held by EU national central banks that did not use the euro. This meant that the ratio of one NCB’s sovereign-debt purchases to total PEPP sovereign-debt purchases could vary during the program so long as the ratios converged to the capital-key percentages by the program’s end date. In theory, the Bank of Greece could purchase the total amount of sovereign debt authorized in early stages of the PEPP so long as its percentage of total public-sector purchases returned to 2.47% by the end of the PEPP. The APP, by contrast, required national central banks to conduct purchases in step with the capital key. Continuing with the example, when the ECB raised the amount authorized under the APP, the Bank of Greece would purchase 2.47% of the increased amount. The lifting of these restrictions—that purchases be made in step with the capital key and that the PEPP could purchase no more than 33% of a single member state’s issue—stoked fears that the PEPP would prop up fledgling member states (Arnold and Stubbington 2020).

In addition, eurozone members had issued large amounts of sovereign debt during COVID-19. An ECB official argued that the PEPP’s flexibility allowed it to stabilize markets when countries issued large amounts of debt (Lane 2020a). Lagarde (2020b, 7) asserted that:

The capital keys are the benchmarks. Flexibility is the key principle that distinguishes the PEPP from the others. We will never let capital key convergence that will take place at some stage impair the efficiency of the monetary policy that we have to deploy.

Through January 2022, purchases from most eurozone members aligned closely with the ratios prescribed by the capital key. Figure 8 shows how far member states strayed from the capital key by subtracting the capital-key percentage from the percentage of cumulative PEPP purchases of that member’s debt. Purchases of most issuers’ debt stayed within a percentage point throughout the PEPP, but purchases of France and Italy diverged from specified ratios by more than four percentage points in 2020.FIn July 2020, one percentage point of cumulative PSPP purchases equaled EUR 3.6 billion; in January 2022, one percentage point equaled EUR 14.6 billion (ECB 2020c). By 2022, purchases of French and Italian debt were converging on the Eurosystem capital key.

Figure 8: Difference Between PEPP Proportions and Capital-Key Proportions

Source: ECB 2020c.

Source: ECB 2020c.

Haircuts

1

No haircuts were applied because the PEPP did not engage in lending.

Interest Rate

1

The PEPP did not specify interest rates because it did not engage in lending.

Fees

1

No documents suggest that the ECB charged fees to issuers of securities that it purchased.

Term

1

No documents suggest that the ECB changed the terms of securities that it purchased.

Other Conditions

1

Documents do not indicate other conditions beyond those discussed elsewhere in the case.

Regulatory Relief

1

Documents surveyed do not suggest that the Eurosystem provided regulatory relief—beyond that already described in the case—to financial institutions participating in the PEPP.

International Cooperation

1

The Eurosystem consisted of the ECB and 19 NCBs. Coordination within the Eurosystem was regulated by the Governing Council of the ECB and its guidelines (ECB 2006). The Eurosystem did not coordinate with other governments inside or outside of the EU.

Duration

1

As of August 2021, the ECB continued to purchase securities through the PEPP. It originally projected to complete purchases by June 2021, with maturing principal reinvested until the end of 2022 (ECB 2020f). The ECB followed this decision by increasing the envelope size in response to subsequent outbreaks of COVID-19 and its variants. The ECB also extended the timeframe for PEPP purchases “until at least the end of March 2022 and, in any case, until it judge[d] that the coronavirus crisis phase [wa]s over” (ECB 2021f). To meet the new EUR 1.85 trillion authority, the Governing Council decided to accelerate asset purchases. The Governing Council committed to reinvest principal from its maturing securities until at least the end of 2023.

Key Program Documents

-

(DNB 2020) De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB). May 1, 2020. “Information on Reverse Auctions by DNB.”

DNB’s terms and conditions for PEPP and PSPP reverse auctions.

-

(ECB 2020a) European Central Bank (ECB). 2021 2020. “Daily Liquidity Conditions.”

Data showing liquidity programs in the Eurosystem.

-

(ECB 2020b) European Central Bank (ECB). 2021-05 2020. “History of PEPP Purchases Broken down by Asset Category.”

Data disaggregating PEPP purchases over time by asset category.

-

(ECB 2020c) European Central Bank (ECB). 2021-05 2020. “History of Public Sector Securities Cumulative Purchase Breakdowns under the PEPP.”

Data showing PEPP purchase amounts of member-state debt.

-

(ECB 2020d) European Central Bank (ECB). October 30, 2020. “Third Covered Bond Purchase Programme (CBPP3).” Questions and answers. European Central Bank.

FAQs on the Eurosystem’s third covered bond purchase programme (CBPP3).

-

(ECB 2021a) European Central Bank (ECB). May 20, 2021. “Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP).” European Central Bank.

Technical details regarding the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) of marketable debt instruments issued by euro area central governments, certain agencies, international, or supranational institutions located in the euro area.

-

(ECB 2021b) European Central Bank (ECB). June 28, 2021. “Asset Purchase Programmes.” European Central Bank.

Web page summarizing the APP.

-

(ECB 2021c) European Central Bank (ECB). July 5, 2021. “Asset-Backed Securities Purchase Programme (ABSPP).” Questions and answers. European Central Bank.

Web page answering technical questions about implementation of the ABSPP.

-

(ECB 2021d) European Central Bank (ECB). July 15, 2021. “Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP).” Questions and answers. European Central Bank.

Web page answering technical questions about implementation of the CSPP.

-

(ECB 2021e) European Central Bank (ECB). August 16, 2021. “Securities Lending.” European Central Bank.

General PSPP securities lending framework and securities lending arrangements of the ECB.

-

(ECB, n.d.) European Central Bank (ECB). No date. “Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) Questions & Answers.” Accessed April 19, 2021.

FAQs detailing specific terms and exemptions of the PEPP’s rules. s

-

(Fitch Ratings, n.d.) Fitch Ratings. No date. “Greece Credit Ratings.” Accessed June 30, 2021.

Web page showing credit ratings for Greek sovereign debt.

-

(C/2016/6447 2016) Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1801 of 11 October 2016 on Laying down Implementing Technical Standards with Regard to the Mapping of Credit Assessments of External Credit Assessment Institutions for Securitisation in Accordance with Regulation (EU) No 575/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council. October 12, 2016. 275 OJ L. COM: 32016R1801.

Technical document presenting the framework and credit-rating schedule used by the PEPP.

-

(ECB/2014/45 2015) Decision (EU) 2015/5 of the European Central Bank of 19 November 2014 on the Implementation of the Asset-Backed Securities Purchase Programme. January 6, 2015. 001 OJ L. ECB: 32014D0045(01).

Most recent decision renewing the ABSPP and setting eligibility criteria.

-

(ECB/2016/16 2016) Decision (EU) 2016/948 of the European Central Bank of 1 June 2016 on the Implementation of the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme. June 15, 2016. 157 OJ L. ECB: 32016D0016.

Most recent decision renewing the CSPP and setting eligibility criteria.

-

(ECB/2020/8 2020) Decision (EU) 2020/187 of the European Central Bank of 3 February 2020 on the Implementation of the Third Covered Bond Purchase Programme (Recast). February 12, 2020. 039 OJ L. ECB: 32020D0187.

Most recent decision renewing the CBPP3 and setting eligibility criteria.

-

(ECB/2020/9 2020) Decision (EU) 2020/188 of the European Central Bank of 3 February 2020 on a Secondary Markets Public Sector Asset Purchase Programme. February 12, 2020. 039 OJ L. ECB: 32020D0188.

Most recent decision renewing the PSPP and setting eligibility criteria.

-

(ECB/2020/17 2020) Decision (EU) 2020/440 of the European Central Bank of 24 March 2020 on a Temporary Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme. March 25, 2020. 091 OJ L. ECB: 32020D0440.

Decision establishing the PEPP, providing rationale, and describing eligibility criteria (though mostly in reference to APP programs).

-

(ECB 2006) European Central Bank (ECB). December 13, 2006. “Guideline of the European Central Bank of 31 August 2006 Amending Guideline ECB/2000/7 on Monetary Policy Instruments and Procedures of the Eurosystem.” Official Journal of the European Union 49 (L 352): 1–90.

ECB’s pre-crisis policies and a general primer on how the Eurosystem functions.

-

(Gauweiler and Others v. Deutscher Bundestag 2015) June 16, 2015. Court of Justice of the European Union (No. ECLI:EU:C:2015:400). C-62/14 EUR-Lex.

Case challenging the authority of the ECB to conduct Outright Monetary Purchases.

-

(TFEU [1957] 2012) Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. October 26, (1957) 2012. 326/1 C 37.

Treaty restricting the ECB from, among other activities, monetary financing.

-

(Weiss and Others v. ECB 2018) December 11, 2018. Court of Justice of the European Union (No. ECLI:EU:C:2018:1000). C-493/17 EUR-Lex.

Case challenging the authority of the ECB to conduct the PSPP.

-

(European Union 1992) European Union. July 29, 1992. “Protocol (No 18) on the Statute of the European System of Central Banks and of the European Central Bank.” Official Journal of the European Communities. Treaty on European Union. C:1992:191:TOC. EUR-Lex.

Protocol annexed to the Treaty on European Union authorizing the ECSB; article 18 authorizes the ECB and national central banks to undertake open-market operations including repurchase agreements and lending.

-

(Reuters 2020) “Italy Furious at ECB’s Lagarde ‘not Here to Close Spreads’ Comment.” March 12, 2020, sec. U.S. Markets.

Article describing the reaction of Italian political figures to Lagarde’s comments, which pushed Italian sovereign debt yields higher.

-

(ECB 2020e) European Central Bank (ECB). March 18, 2020. “ECB Announces €750 Billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP).” Press release.

Press release announcing the PEPP.

-

(ECB 2020f) European Central Bank (ECB). June 4, 2020. “Monetary Policy Decisions.” Press release.

Press release announcing PEPP size increase.

-

(ECB 2021f) European Central Bank (ECB). March 11, 2021. “Monetary Policy Decisions.” Press Release.

Press release describing policy rate cut as a response to COVID-19.

-

(de Guindos and Schnabel 2020) Guindos, Luis de, and Isabel Schnabel. April 3, 2020. “The ECB’s Commercial Paper Purchases: A Targeted Response to the Economic Disturbances Caused by COVID-19.” The ECB Blog (blog).

Blog post articulating why the ECB sought to purchase commercial paper.

-

(Lagarde 2020a) Lagarde, Christine. June 4, 2020. Questions and answers. Questions and answers presented at the European Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main, June 4.

Press conference questions for Christine Lagarde following the announcement that the PEPP’s size would grow.

-

(Lagarde 2020b) Lagarde, Christine. July 16, 2020. Questions and answers. Questions and answers presented at the European Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main, July 16.

Journalists’ questions following the ECB press conference and addressing fragmentation in the eurozone.

-

(Lagarde 2020c) Lagarde, Christine. September 10, 2020. Questions and answers. Questions and answers presented at the European Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main, September 10.

Journalists’ questions following the ECB press conference.

-

(Lagarde and de Guindos 2020) Lagarde, Christine, and Luis de Guindos. March 12, 2020. Questions and answers. Questions and answers presented at the European Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main, March 12.

Journalists’ questions before the PEPP was announced; ECB President Lagarde said that the Governing Council was “not here to close spreads.”

-

(Lane 2020a) Lane, Philip R. June 22, 2020. “The Market Stabilisation Role of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme.” European Central Bank (blog).

Blog post articulating the purpose of the PEPP distinct from the macroeconomic objectives of the APP.

-

(Lane 2020b) Lane, Philip R. August 27, 2020. “The Pandemic Emergency: The Three Challenges for the ECB.” Slides presented at the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, August 27.

Presentation by ECB vice president describing the ECB’s response to COVID-19.

-

(OECD 2007–2021) Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2007–2021. “Long-Term Government Bond Yields: 10-Year.” Main Economic Indicators. IRLTLT01[XX]M156N. Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED).

Monthly data recording the yields of 10-year government bonds issued by selected eurozone countries; each series identifier can be constructed using ISO-3166-1 alpha-2 codes.

-

(Schnabel 2021) Schnabel, Isabel. February 18, 2021. “The ECB’s Policy Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Slides presented at the Booth School of Business, University of Chicago, February 18.

Presentation by ECB vice president describing the package of policies it used to respond to COVID-19.

-

(Berenberg-Gossler, Enderlein, Fiedler, Gern, Raddant, Stolzenburg, Blot, et al. 2016) Berenberg-Gossler, Paul, Henrik Enderlein, Salomon Fiedler, Klaus-Jürgen Gern, Matthias Raddant, Ulrich Stolzenburg, Christophe Blot, et al. September 26, 2016. “Financial Market Fragmentation in the Euro Area: State of Play.” In-Depth Analysis PE 587.314. Monetary Dialogue Papers.

Analysis requested by the European Parliament’s Monetary Expert Panel assessing the risks of financial fragmentation.

-

(ECB 2017) European Central Bank (ECB). 2017. “Base Money, Broad Money and the APP.” ECB Economic Bulletin, Boxes, no. 6: 62–65.

Note describing money-supply fluctuations and the settlement system of the APP.

-

(Hammermann, Leonard, Nardelli, and von Landesberger 2019) Hammermann, Felix, Kieran Leonard, Stefano Nardelli, and Julian von Landesberger. March 18, 2019. “Taking Stock of the Eurosystem’s Asset Purchase Programme after the End of Net Asset Purchases.” ECB Economic Bulletin, March.

Article diving deep into the implementation aspects of the APP, which were mostly duplicated by the PEPP.

-

(Avdjiev, Everett, and Shin 2019) Avdjiev, Stefan, Mary Everett, and Hyun Song Shin. March 5, 2019. “Following the Imprint of the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme on Global Bond and Deposit Flows.” BIS Quarterly Review, March, 69–81.

Journal article describing the residency of APP counterparties.

-

(Benigno, Canofari, Bartolomeo, and Messori 2020) Benigno, Pierpaolo, Paolo Canofari, Giovanni Di Bartolomeo, and Marcello Messori. September 2020. “Theory, Evidence, and Risks of the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme.” In-Depth Analysis PE 652.746. Monetary Dialogue Papers.

Study discussing the economic theory behind, and the evidence of, the APP and PEPP.

-

(Blot, Creel, and Hubert 2020) Blot, Christophe, Jérôme Creel, and Paul Hubert. September 30, 2020. “APP vs PEPP: Similar, But With Different Rationales.” Study PE 652.743. Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies.

Paper analyzing the PEPP’s role preventing the fragmentation of eurozone economies.

-

(Grund 2020) Grund, Sebastian. March 25, 2020. “Legal, Compliant and Suitable: The ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP).” Policy Brief. Repair and Prepare.

Article arguing that the PEPP was created legally.

-

(Runkel 2022a) Runkel, Corey N. Forthcoming. “Greece Emergency Liquidity Assistance.” Journal of Financial Crises.

YPFS case study reviewing the Bank of Greece’s (and the ECB’s) Emergency Liquidity Assistance.

-

(Runkel 2022b) Runkel, Corey N. Forthcoming. “Term Auction Facility.” Journal of Financial Crises, Broad-Based Emergency Liquidity 4 (2).

YPFS case study reviewing the Federal Reserve’s Term Auction Facility during the Global Financial Crisis.

-

(Smith 2020a) Smith, Ariel. October 8, 2020. “The European Central Bank’s Covered Bond Purchase Programs I and II.” Journal of Financial Crises, Market Liquidity 2 (3): 382–404.

YPFS case study reviewing the ECB’s CBPP1 and CBPP2.

-

(Smith 2020b) Smith, Ariel. October 8, 2020. “The European Central Bank’s Securities Markets Programme.” Journal of Financial Crises, Market Liquidity 2 (3): 369–81.

YPFS case study reviewing the ECB’s CBPP1 and CBPP2.

-

(Arnold and Stubbington 2020) Arnold, Martin, and Tommy Stubbington. March 26, 2020. “ECB Shakes off Limits on New €750bn Bond Buying Plan.” Financial Times. Frankfurt.

Article analyzing the unannounced change removing the purchase limits on public-sector securities.

European Banking Authority credit ratings

Source: C/2016/6447 2016.

Source: C/2016/6447 2016.

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Market Support Programs

Countries and Regions:

- Euro Zone

Crises:

- COVID-19