Blanket Guarantee Programs

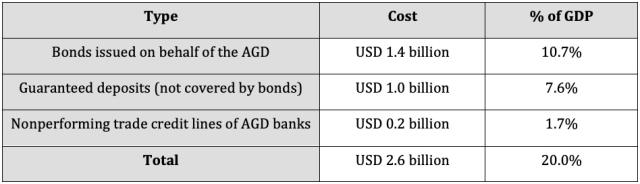

Ecuador: Blanket Guarantee, 1998

Purpose

In terms of trade lines, to “persuade lenders to restore credit lines to pre-September 1998 levels” and to stem the banking crisis (Republic of Ecuador 2000b, 60). In terms of deposits, to “restore stability in bank liabilities” and prevent deposit runs (Jácome H. 2004, 19, 29)

Key Terms

-

Launch DatesDecember 1, 1998, for trade lines and deposits

-

End DateMarch 2000 for trade financing; March 2004 for deposits

-

Eligible InstitutionsFor trade lines: All lenders; For deposits: Banks, finance companies, savings and loan cooperatives, leasing companies, credit card issuers, brokerage houses, insurance companies

-

Eligible AccountsTrade financing; deposits with certain restrictions

-

CoverageAs of August 2020: USD 2.6 billion in total liabilities; USD 800 million–USD 850 million in deposits

-

OutcomesUnclear

-

Notable FeaturesBank holiday and deposit freeze; 1% tax on all financial transactions

After a series of exogenous shocks hit the Ecuadorian economy in 1997–1998, foreign creditors reassessed their emerging-market risk and reduced external credit lines to Ecuador, thus draining liquidity. The closure of a small bank called Solbanco in April 1998 triggered deposit runs at other banks. Banks sought assistance from the Central Bank of Ecuador (Banco Central del Ecuador, or BCE). By the end of September 1998, the BCE had issued emergency loans to 11 financial institutions, totaling nearly 30% of the money base. The crisis accelerated in August 1998 when Banco de Prestamos, the sixth-largest bank, was closed; the existing limited deposit insurance scheme covered only small savers, after a delay, and with haircuts reflecting the depreciation of the sucre. A flight to quality followed, as depositors shifted from sucre deposits to US dollar deposits. On December 1, 1998, the Ecuadorian government created the Deposit Guarantee Agency (Agencia de Garantía de Depósitos, or AGD) to restore stability in bank liabilities. The AGD guaranteed trade credit lines and all bank deposits. It also resolved banks, mainly through purchase and assumption transactions. The government also imposed a 1% tax on all financial transactions to support public finances; the tax, imposed amidst a liquidity crunch, accelerated the collapse of several financial institutions, including Ecuador’s largest bank. During the blanket deposit guarantee, the government announced a surprise bank holiday, partial deposit freeze, and uncertain schedule for the partial deposit freeze lift. The trade credit line guarantee ended as of March 2000. The AGD phased out blanket deposit coverage between 2001 and 2004. The AGD closed after 11 years on December 31, 2009, replaced by the Deposit Security Corporation (Corporación del Seguro de Depósitos, or COSEDE). COSEDE covers depositors up to USD 31,000.

In Ecuador, late 20th century financial liberalization, foreign capital inflows, and lax prudential regulation allowed financial intermediaries to engage in risky lending, which created a boom and bust cycle during the 1990s (Jácome H. 2004; Martinez 2006). Credit climbed in real terms by 40% in 1993 and 50% in 1994. A series of exogenous shocks in 1995 prompted a bust in Ecuador: a banking crisis in Mexico, border conflicts, energy crises, natural disasters, and governance problems, among other issues (Hidalgo Loffredo, Yturralde Farah, and Maluk Salem 1999; Jácome H. 2004). To stem capital outflows, the Central Bank of Ecuador (Banco Central del Ecuador, or BCE) increased open market operations to contract Ecuador’s money base, stabilize the exchange rate, and temper inflation. However, the increase in BCE’s interest rate led financial intermediaries with maturity mismatch problems into severe liquidity issues. Though the BCE provided banks with liquidity support at the time, the banking system remained fragile and vulnerable to future external shocks (Jácome H. 2004; Martinez 2006).

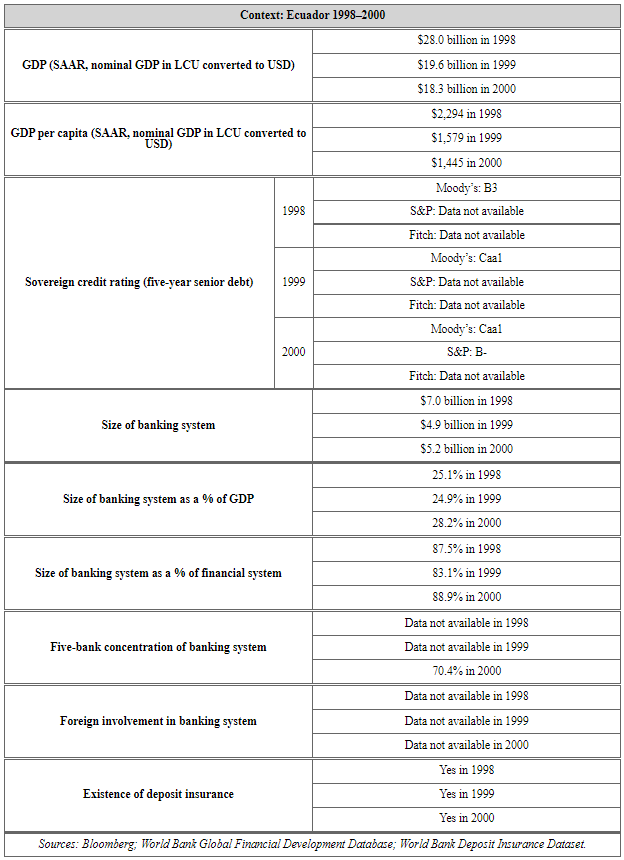

Another series of shocks hit the Ecuadorian economy and impaired bank assets in 1997–1998, including El Niño floods that destroyed agricultural areas, the Russian financial crisis, the Brazilian financial crisis, and plummeting oil prices (EIU 2004; Jácome H. 2004; Republic of Ecuador 2000a; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). Foreign creditors reassessed their emerging-market risk and reduced international interbank and trade lines by USD 300 million in the fourth quarter of 1998 (see Figure 1) (de la Torre, García-Saltos, and Mascaró 2001; IMF 2000b; Jácome H. 2004). The USD 300 million reduction in external trade lines totaled 17% of all credit lines and 20% of the CBE’s international reserves at the time (Jácome H. 2004). The weakest banks increased distressed borrowing in response to the liquidity crunch (de la Torre, García-Saltos, and Mascaró 2001).

The closure of a small bank called Solbanco in April 1998 prompted contagion and deposit runs at other banks, including two of the three largest banks in Ecuador (de la Torre, García-Saltos, and Mascaró 2001; Jácome H. 2004). Banks sought assistance from the BCE, which responded by issuing emergency loans to 11 financial institutions by the end of September 1998 (Jácome H. 2004).

The BCE also administered a limited deposit insurance scheme, up to approximately USD 8,000 per depositor for domestic and foreign currency deposits—depending on the real exchange rate, since coverage was tied to an inflation-indexed unit. However, the existing limited deposit insurance scheme could not sufficiently cover payouts when Banco de Prestamos, the sixth-largest bank in terms of assets, was closed. Small Banco de Prestamos savers did receive payouts, but only after several weeks and after the value of payouts had eroded due to inflation and the depreciation of the Ecuadorian sucre (ECS). Some large creditors did not recover payouts even after several years (EIU 2004; Jácome H. 2004). There followed a flight to quality in the autumn of 1998, as sucre deposits shifted to US dollar deposits (Jácome H. 2004).

Figure 1: External Credit Lines of the Ecuadorian Banking System (USD millions)

(1/98 = Jan. 1998)

Source: IMF 2000b.

Source: IMF 2000b.

On December 1, 1998, the Ecuadorian government created the Deposit Guarantee Agency (Agencia de Garantía de Depósitos, or AGD) to restore stability in bank liabilities (El Telégrafo 2014; Jácome H. 2004; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). The government also imposed a 1% tax on all financial transactions—debits and credits—which effectively accelerated the financial collapse of various banks, including the largest bank in the system measured by deposits, Banco del Progreso (EIU 2004; Jácome H. 2004). Demand deposits in the banking system fell by 17% in January 1999 (Jácome H. 2004).

In November 1999, Congress passed another law that allowed the AGD to cover deposit guarantees for Banco de Prestamos (Dow Jones 1998; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). This bank was not previously eligible for the blanket guarantee because its liquidation began before the AGD’s creation; depositors had already received USD 2,000 under the preceding limited deposit insurance scheme (IMF 2000b; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). The fiscal cost of Banco de Prestamos’ inclusion in the blanket guarantee was USD 200 million (IMF 2000b).

On March 8, 1999, then–Bank Superintendent Jorge Egas declared a surprise bank holiday to “preserve the stability of bank reserves, limit the withdrawals that could [affect] the domestic financial system, and avoid pressure on the currency and the continued rise in prices” (AP 1999). The bank holiday lasted from March 8 through March 12, 1999 (IMF 2000a).

On March 11, 1999, the president and finance minister announced a one-year partial freeze on deposits, which prompted depositors to withdraw ECS 1.7 billion (USD 147,288)FUSD 1 = ECS 11,542 on March 11, 1999, according to Bloomberg. according to the BCE (see Key Design Decision No. 2, Part of a Package) (WSJ 1999).

On September 30, 1999, Ecuador became the first country to ever default on its Brady bondsFBrady bonds are sovereign debt securities with long-term maturities, denominated in US dollars and partially backed by US Treasury bonds. Starting in 1989, emerging-market countries began to issue Brady bonds to restructure their debt following the Latin American debt crisis (Crenson 1999; Fed 1998). after it failed to make a USD 98 million interest payment. Ecuador owed USD 6 billion to bondholders in total (Crenson 1999).

Sixteen financial institutions, comprising 65% of Ecuador’s onshore assets, were intervened or closed by the AGD by the beginning of January 2000 (IMF 2000b).

On January 9, 2000, Ecuador adopted the US dollar as its official currency (Republic of Ecuador 2000b). The transition from sucres to US dollars occurred between April and September 2000 (see Key Design Decision No. 2, Part of a Package) (EIU 2004).

On April 19, 2000, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a one-year standby arrangement with Ecuador for special drawing right (SDR) 226.7 million (USD 170 million)FUSD 1 = SDR 0.75 on April 19, 2000, according to the IMF. (IMF 2000a; Republic of Ecuador 2000a; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). This allowed Ecuador to receive additional funding from the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the Andean Development Corporation. Disbursements through June 30, 2000, exceeded USD 193.3 million, and commitments through December 31, 2000, exceeded USD 719 million (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

More than 90% of depositors received their full deposits back by mid-2000, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit (2004). However, some large depositors with deposits of more than USD 10,000 had still not received payouts (EIU 2004).

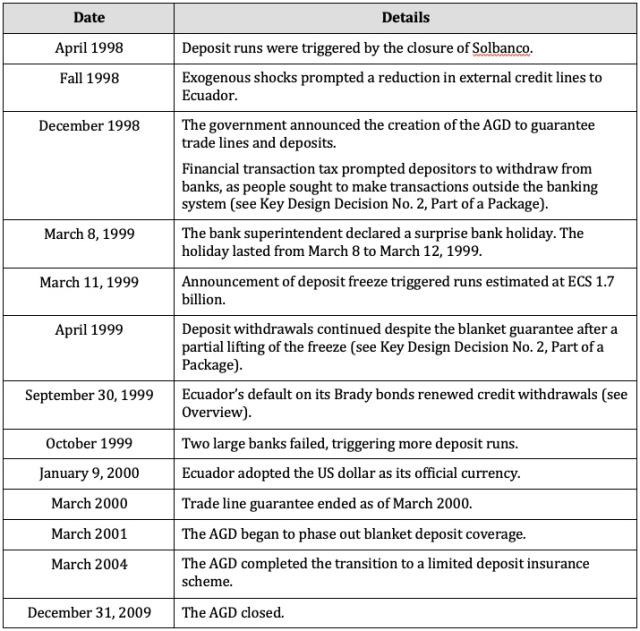

The AGD phased out blanket deposit coverage between 2001 and 2004 (see Key Design Decision No. 13, Duration) (Republic of Ecuador 2000b; Republic of Ecuador 2000).

On December 10, 2008, the Ecuadorian Transitional Congress passed the Law of Financial Security, which outlined the replacement of the AGD by a new body: the Deposit Security Corporation (Corporación del Seguro de Depósitos, or COSEDE). The law gave a 12-month transition period plus a potential six-month grace period after the AGD’s closure (EIU 2009; Global Insight Daily Analysis 2008). The AGD transferred USD 133 million to COSEDE’s new Deposit Insurance Fund in January 2009 (COSEDE 2013).

The AGD closed after 11 years on December 31, 2009 (El Comercio 2009). Today, the COSEDE manages deposit insurance in Ecuador and covers up to USD 31,000 per depositor (COSEDE n.d.; COSEDE Law n.d.; COSEDE 2013).

The BCE president, Luis Jácome, and board of directors resigned en masse on March 12, 1999, to protest the freezing of bank deposits by the president and Ministry of Finance (Alvaro and Tedesco 1999). In an IMF working paper, Jácome says that the guarantee was “seemingly a desperate decision to contain mounting bank deposit withdrawals” (2004, 25). In Jácome’s view, in guaranteeing deposits and trade lines, the government printed a “massive” amount of money, thus contributing to monetary instability and moral hazard. He also criticizes the government’s execution, communication, and other policies around the guarantee. In Jácome’s view, the lagged payouts imposed losses on depositors, prompting further contagion and deposit runs; the bank holiday and deposit freeze communicated the message that all banks were impaired, promoting a systemic lack of confidence; and the “devastating” tax on financial transactions accelerated financial institutions’ collapse during the midst of a liquidity crunch (Jácome H. 2004).

Three academics—Denisse S. Hidalgo Loffredo, Omar R. Yturralde Farah, and Omar Maluk Salem—have similarly criticized the AGD’s administration and expertise. They argue that lagged deposit insurance payments were poor practices amidst domestic currency depreciation (Hidalgo Loffredo, Yturralde Farah, and Maluk Salem 1999).

According to a publication from the World Bank, Ecuador’s guarantees lacked credibility, thereby undermining their effectiveness. The argument asserts that deposit guarantees were more credible at smaller institutions, since there was less confidence that the government could keep large banks open and fully honor all deposits (Beckerman and Solimano 2002).

For a paper published in the Cambridge Journal of Economics, Gabriel X. Martinez interviewed bankers, businesspeople, regulators, economics analysts, and authorities about Ecuador’s financial crisis. Some of Martinez’s interviewees say that regulators had conflicts of interest during the crisis “because of their connections with and dependence on the banking and political systems” (Martinez 2006, 573). After Ecuador’s financial liberalization, “nearly all” banking superintendents were well connected with the private sector (Martinez 2006).

An IMF report concludes that there was “little credibility in the deposit guarantee” given Ecuador’s weak fiscal position and the insolvency of several large banks (IMF 2000b, 26). The IMF also characterizes Ecuador’s bank restructuring implementation as “uneven” with “strong” conflict of interest problems between the government and private sector (IMF 2000b, 27). The government also made political decisions that increased the costs to the government, the IMF finds. One example of a political decision that the IMF mentions is the bailout of Solbanco’s shareholders in July 1999. Solbanco’s main depositor, a public employees’ pension fund, had converted part of its deposits into equity to help Solbanco build capital in 1998; when the bank’s problems worsened in 1999, the government reversed that conversion, turning the new shares into insured deposits. The IMF estimates that decision cost USD 75 million (IMF 2000b).

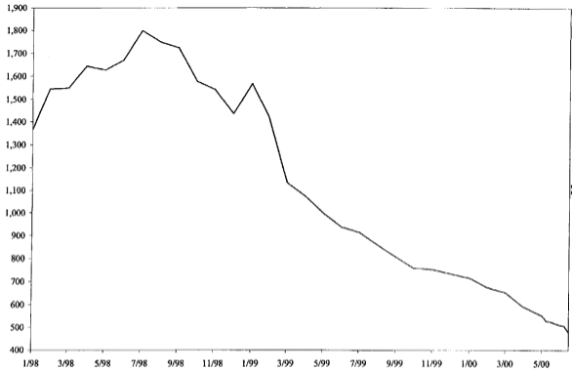

The IMF says that the financial transactions tax exacerbated Ecuador’s liquidity crunch. In the same report, the IMF estimates the fiscal cost of Ecuador’s crisis response, concluding that poor policy choices added “substantially” to this cost (see Figure 2) (IMF 2000b).

Figure 2: Crisis Fiscal Cost (as of June 2000)

Source: IMF 2000b

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

1

Depositors ran on Ecuadorian banks after the small bank Solbanco closed in April 1998; runs and closures continued throughout 1998 (de la Torre, García-Saltos, and Mascaró 2001; Jácome H. 2004). The government created the AGD to “restore stability in bank liabilities” and prevent deposit runs, according to then–BCE President Luis Jácome in a retrospective IMF working paper (2004, 19, 29).

A series of exogenous shocks hit the Ecuadorian economy and impaired bank assets in 1997–1998, including El Niño floods that destroyed agricultural areas, the Russian financial crisis, the Brazilian financial crisis, and plummeting oil prices (EIU 2004; Jácome H. 2004; Republic of Ecuador 2000a; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). Foreign creditors reassessed their emerging-market risk and reduced international interbank and trade lines by USD 300 million in the fourth quarter of 1998 (IMF 2000b; de la Torre, García-Saltos, and Mascaró 2001). The USD 300 million reduction in external trade lines totaled 17% of all credit lines and 20% of the CBE’s international reserves at the time (Jácome H. 2004). A bond prospectus on behalf of Ecuador in August 2000 said that “the Government intend[ed] to persuade lenders to restore credit lines to pre-September 1998 levels” with the trade line guarantee (Republic of Ecuador 2000b, 60). The government stated that failure to restore credit lines to Ecuadorian banks would further aggravate the banking crisis (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Part of a Package

1

Bank Holiday and Deposit Freeze

On March 8, 1999, then–Bank Superintendent Jorge Egas declared a surprise bank holiday to “preserve the stability of bank reserves, limit the withdrawals that could [affect] the domestic financial system, and avoid pressure on the currency and the continued rise in prices” (AP 1999). The bank holiday lasted from March 8 through March 12, 1999 (IMF 2000a; Republic of Ecuador 2000a).

On March 11, 1999, the president and finance minister announced a partial freezeFIn light of the partial freeze, depositors could request negotiable claims on their respective banks (certificates of reprogrammed deposits; certificados de depósito reprogrammable, or CDRs) with a discount that differed according to market perception about respective banks’ strength. Depositors could use CDRs to buy durable consumer goods and real estate (Jácome H. 2004). A government decree in November 1999 forced banks to accept CDRs as payments of credits at face value, up to the amount of credit lines granted to each bank by the National Financial Corporation (Corporación Financiera Nacional, or CFN). The CFN was a second-tier development bank. Banks could use CDRs to cancel CFN lines. According to the IMF, this November 1999 decree negatively affected banks’ liquidity and portfolio structure and caused the technical bankruptcy of the CFN (IMF 2000b). on deposits following the bank holiday to protect the system against speculative attacks and runs (Alvaro and Tedesco 1999; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). Sources differ on the exact details of the freeze.FSee Alvaro and Tedesco 1999; Dow Jones 1999a; IMF 2000a (28); Jácome H. 2004 (22); Republic of Ecuador 2000b (27, 59). After the announcement, depositors further withdrew ECS 1.7 billion, according to the BCE (WSJ 1999).

In testimony before the Fiscal Committee in Congress on March 30, 1999, former BCE President Jácome said:

The bank holiday and the freeze on deposits have caused high economic and social costs and have tended to generate distrust in the country’s banking system, which in turn prompted bank withdrawals of about ECS 1.7 billion from citizens and businesses. (Dow Jones 1999b)

By April 1999, the government unfroze the deposits of those over 65 years old, those with a terminal illness, foreign depositors, and accounts belonging to nongovernmental organizations and public institutions (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

The Constitutional TribunalFThe Constitutional Tribunal was the highest court in Ecuador at the time and had final authority on constitutional interpretation (Dow Jones 2007). declared account freezes unconstitutional in December 1999. Though the government issued a resolution that scheduled the unfreezing of accounts, it appears that this was delayed and revised for several months. One issue was whether to pay guaranteed deposits in (1) a combination of cash and bonds or (2) cash only (Republic of Ecuador 2000b). The AGD paid deposit guarantees in cash only at first and with additional bonds after dollarization (see Key Design Decision No. 11, Process for Exercising Guarantee).

Frozen accounts comprised 33.3% of total deposits in the financial system as of June 30, 1999. The freeze significantly contracted liquidity and virtually halted all financial activity (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Financial Transaction Tax

The legislation establishing the AGD also eliminated the income tax (El Telégrafo 2014). However, the Law for Economic Transformation imposed a 1% tax on all financial transactions—debits and credits—to substitute the income tax and support public finances (Jácome H. 2004; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). The Economist Intelligence Unit and Jácome argue that this tax effectively accelerated the financial collapse of various banks, including the largest bank in the system measured by deposits, Banco del Progreso. They also argue that the tax prompted depositors to withdraw their money from banks, thus undermining the blanket guarantee’s goal of stabilizing bank liabilities (EIU 2004; Jácome H. 2004). In October 1999, Ecuador had collected ECS 509.9 billion (USD 3 million)FPer contemporaneous reporting by Reuters, USD 1 = ECS 16,775 on November 10, 1999 (Remond 1999). in revenue from the financial transactions tax, according to the Ministry of Finance (Alvaro 1999b).

On November 5, 1999, the Ecuadorian Congress approved a tax reform bill that would lower the 1% financial transaction tax to 0.8% on January 1, 2000. The bill also reestablished a personal income tax on individuals who made at least ECS 80 million (USD 4,776) per year; rates ran from 5% to 25%. This tax reform provided the basis for the government’s annual budget for 2000. It was also a key condition for the IMF loan in 2000, according to then–Economy Minister Javier Espinosa and then–IMF First Deputy Managing Director Stanley Fisher (Alvaro 1999a; Fischer 2000).

The November 1999 tax reform did not inspire confidence among creditors, given the reform’s narrow tax base, then–President Jamil Mahuad’s fragile coalition, and the lack of information provided by the government (Remond 1999).

Dollarization

On January 9, 2000, Ecuador adopted the US dollar as its official currencyFThe Ecuadorian Constitution forbade the outright elimination of the sucre, so the sucre remained as a fractional currency (Republic of Ecuador 2000b, 29; The Economist 2004). (Republic of Ecuador 2000b). To this end, authorities pegged the sucre at ECS 25,000 to the US dollar, withdrew the sucre from circulation, and replaced sucres with US dollars between April and September 2000. By September 2000, this process was largely complete (EIU 2004). In a bond prospectus dated August 23, 2000, the government stated that it expected dollarization to lower inflation, eliminate exchange rate risk, reverse capital flight, and render the economy more transparent to both Ecuadorians and foreign investors (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Dollarization limited the BCE’s ability to provide liquidity support to the banking system. Therefore, the government began to develop a mechanism to recycle liquidity within the banking system: the sale of US dollar-denominated bonds combined with repurchase operations—together with a BCE liquidity support facility (Republic of Ecuador 2000a; Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Legal Authority

1

Previously, the 1992 Monetary Regime and State Bank Law allowed the central bank to use its funds to provide limited deposit insurance in sucres when a bank closed (BCE n.d.; Jácome H. 2004).

The Law for the Economic Transformation of Ecuador authorized the creation of the AGD on December 1, 1998 (El Telégrafo 2014; Law for Economic Transformation 1998, art. 144). The Law for Economic Transformation also allowed the AGD to resolve failing banks through purchase and assumption (P&A) transactions (Jácome H. 2004). The Law for Economic Transformation also eliminated the income tax in December 1998, though it was later reinstated (see Key Design Decision No. 2, Part of a Package) (El Telégrafo 2014).

Congress passed another law in November 1999 that allowed the AGD to use public funds to cover deposit guarantees for Banco de Prestamos (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Administration

1

The AGD’s board of directors appointed a nonvoting member to be the general manager of the AGD (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

At least once per month, the AGD board evaluated information provided by the Superintendency of Banks and CBE on the financial system and on each institution to determine preventive or corrective policies (Hidalgo Loffredo, Yturralde Farah, and Maluk Salem 1999).

Governance

1

A board of directors administered the AGD, headed by the superintendent of banks. The board also included the minister of finance, a director from the BCE, and a delegate appointed by the president. The board’s general manager was a nonvoting member appointed by the board itself (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Communication

1

Research did not uncover contemporaneous announcements or characterizations of the guarantee from the Ecuadorian government, including the Ministry of Finance and AGD.

Former BCE President Jácome argues that the bank holiday and deposit freeze signaled the government’s inability to stabilize the financial system. In his view, these measures promoted rather than prevented bank runs (Jácome H. 2004).

According to the IMF, the government achieved a temporary resurgence in public confidence in the banking system when it announced the results of its bank audits and next stepsFSee Key Design Decision No. 11, Process for Exercising Guarantee. Capital compliant “A” banks remained under private control. Capital deficient “B” banks remained operational and underwent a restructuring process. Negative net worth “C” banks were immediately taken over and resolved by the AGD (IMF 2000b; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). on July 30, 1999FConfidence fell again in September 1999 when Ecuador defaulted on its Brady bonds (IMF 2000b). Additional capital flight and further withdrawal of foreign credit renewed liquidity pressure (IMF 2000b). (IMF 2000b).

Source and Size of Funding

1

In August 2000, the government estimated the minimum net fiscal cost of the guarantee to be USD 2.7 billion (or 24% of 2000 GDP) in bond issues and cash transactions to pay out guaranteed deposits (Republic of Ecuador 2000b). External arrears of trade credit lines of intervened banks totaled USD 63 million in 1999 and USD 154 million in 2000 (IMF 2000a).

As provided by the Law for Economic Transformation, the AGD issued bonds to cover the guarantee. Bonds issued on behalf of the AGD for bank recapitalization accrued a monthly simple interest rate of either 12% per annum or the coupon interest rate—whichever was higher from the effective date of issuance. By June 2000, the AGD had issued USD 1.4 billion in bonds (IMF 2000b; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). In August 2000, the government stated that it expected to issue an additional USD 811 million to pay out guaranteed deposits in closed banks—part of which would be offset by asset recovery—and USD 300 million in bonds to capitalize troubled banks in the coming year (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Starting in March 2000, the AGD paid for the guarantee with budgetary allocations and resources recovered from the sales of assets of impaired banks. In August 2000, the government stated that it expected to transfer USD 155 million to the AGD to pay out cash-guaranteed deposits in closed banks (IMF 2000b; Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Though the AGD switched its funding source, it still had the legal ability to issue bonds (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Eligible Institutions

1

The AGD guaranteed trade financings of all lenders until March 2000 (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

The AGD guaranteed deposits of all financial institutions. Under the Financial Institutions Law of 1994, financial institutions included banks, finance companies, savings and loan cooperatives, leasing companies, credit card issuers, brokerage houses, and insurance companies (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Eligible Liabilities

1

The guarantee was unlimited for trade financings of all lenders from December 1998 to March 2000 (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

The guarantee applied to most deposits with certain restrictions (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

The guarantee did not cover deposits that were subject to any right of setoff (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Language in the Law for Economic Transformation explicitly said that the guarantee would not cover deposits in offshore entities (Law for Economic Transformation 1998, art. 21). However, a bond prospectus dated August 23, 2000, stated that the AGD initially intended to guarantee offshore deposits (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Fees

1

Financial institutions paid fees to the AGD of 65 basis points per year of financial institutions’ average deposit balances, broken into monthly payments (Hidalgo Loffredo, Yturralde Farah, and Maluk Salem 1999).

Process for Exercising Guarantee

1

In December 1999, the government signed a three-year restructuring agreement with foreign creditors to restructure USD 63.4 million in trade lines (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

In a Letter of Intent to the IMF dated April 4, 2000, Ecuadorian officials stated that the government was in talks with foreign banks to restructure trade credit lines via the AGD with Brady and euro bonds (Republic of Ecuador 2000). Research did not uncover whether this arrangement actually happened.

Before the bank holiday, deposit freeze, and dollarization, the AGD honored deposit guarantees with cash payments rather than government bonds, as mandated by the state lawyer (Jácome H. 2004; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). After dollarization, the AGD also honored the guarantee with bonds (LatinFinance 2002).

The government hired four international auditing firms to help determine viable and nonviable banks (IMF 2000b; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). The Banking BoardFThe superintendent of banks and Banking Board led the Superintendency of Banks (Republic of Ecuador 2000b). The Banking Board had five members: the superintendent of banks, the general manager of the BCE, two members appointed by the Monetary Board, and one member appointed by the four other members (Hidalgo Loffredo, Yturralde Farah, and Maluk Salem 1999; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). and board of each bank received these results in June 1999 (Republic of Ecuador 2000b). Based on these results, banks were sorted into three categories: capital compliant (“A”), capital deficient (“B”), and negative net worth (“C”). On July 30, 1999, the government publicly announced the results of this audit and next steps: “A” banks remained under private control; “B” banks remained operational and underwent a restructuring process; the AGD immediately took over and resolved “C” banks (IMF 2000b; Republic of Ecuador 2000b). For financial institutions that closed (that is, “C” banks), the AGD sold or transferred the institution’s assets and liabilities, recapitalized the institution, or paid the guaranteed deposits in cash (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

As provided by the Law for Economic Transformation, the AGD capitalized and managed impaired banks through purchase and assumption transactions. P&A occurred when a solvent bank purchased and assumed a proportion of an impaired bank’s assets and liabilities. If assumed liabilities exceeded the purchased assets, the AGD provided the difference in the form of liquid assets to the purchasing bank (Jácome H. 2004).

Other Restrictions

1

The guarantee applied only to deposits with certain interest rates. Until March 2000, the guarantee covered only deposits with interest rates no more than 3% above the average interest rate applied to deposits by banks. The president of Ecuador set the guaranteed maximum deposit interest rate after March 2000, according to the Law for Economic Transformation (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Duration

1

Research did not uncover contemporaneous announcements about the guarantee’s duration, so it is unclear how far in advance duration was predetermined and announced.

The AGD guaranteed trade financing for all lenders from December 1998 to the beginning of March 2000 (Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

In a bond prospectus, dated August 2000, the government disclosed its intention to reduce coverage of deposits in phases, starting in March 2001 (see Figure 3) (Republic of Ecuador 2000; Republic of Ecuador 2000b).

Figure 3: Timeline of Deposit Insurance Transition to USD 8,000

Source: El Comercio 2009; Jácome H. 2004; Republic of Ecuador 2000b.

Source: El Comercio 2009; Jácome H. 2004; Republic of Ecuador 2000b.

On December 10, 2008, the Ecuadorian Transitional Congress passed the Law of Financial Security, which outlined the replacement of the AGD by a new body: COSEDE. The law gave a 12-month transition period plus a potential six-month grace period after the AGD’s closure (EIU 2009; Global Insight Daily Analysis 2008). The AGD transferred USD 133 million to COSEDE’s new Deposit Insurance Fund in January 2009. Today, the COSEDE manages deposit insurance in Ecuador and covers up to USD 31,000 per depositor (COSEDE 2013; COSEDE n.d.; COSEDE Law n.d.).

For a comprehensive timeline of coverage and duration, see Appendix.

Key Program Documents

-

(BCE n.d.) Central Bank of Ecuador (Banco Central del Ecuador, or BCE) (BCE). n.d. “History.” Accessed October 20, 2022.

Web page containing the history of the BCE and AGD.

-

(COSEDE n.d.) Deposit Security Corporation (Corporación del Seguro de Depósitos, or COSEDE) (COSEDE). n.d. “Seguro de Depósitos.” Accessed November 29, 2022.

Web page outlining deposit insurance in Ecuador as of November 2022 (in Spanish).

-

(Fed 1998) Federal Reserve Board of Governors (Fed). 1998. “Brady Bonds and Other Emerging-Markets Bonds.” In Trading and Capital-Markets Activities Manual, Section 4255.1. Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Section of a Fed supervision manual covering Brady bonds in emerging market countries.

-

(Fischer 2000) Fischer, Stanley. 2000. “Ecuador and the IMF—Address by Stanley Fischer.” Address delivered at the Hoover Institution Conference on Currency Unions, Palo Alto, CA, May 19, 2000.

Fisher’s address outlining key economic decisions and events leading to dollarization in Ecuador and the aftermath.

-

(Hidalgo Loffredo, Yturralde Farah, and Maluk Salem 1999) Hidalgo Loffredo, Denisse S., Omar R. Yturralde Farah, and Omar Maluk Salem. 1999. “El Sistema de Seguros de Depósitos en el Ecuador y Sus Efectos en la Economía Nacional.” Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL), Instituto de Ciencias Humanísticas y Económicas Research Paper, February 18, 1999.

Document examining the AGD, its mandate, and its purpose (in Spanish).

-

(Republic of Ecuador 2000a) Republic of Ecuador. 2000. “Ecuador Letter of Intent, Memorandum of Economic Policies, and Technical Memorandum of Understanding.” April 4, 2000.

Letter of intent between the IMF and Ecuador.

-

(COSEDE Law n.d.) Codification of the Management Regulation of Deposit Insurance of the Private and Popular Financial Sectors (COSEDE Law). N.d. Resolution No. COSEDE-DIR-2016-016.

Law establishing deposit insurance under COSEDE.

-

(Law for Economic Transformation 1998) Law for the Economic Transformation of Ecuador (Law for Economic Transformation). 1998.

Legal authority establishing the AGD (in Spanish).

-

(Alvaro 1999a) Alvaro, Mercedes. 1999a. “Ecuador’s Congress Approves Tax Bill; Raises VAT to 12%.” Dow Jones, November 5, 1999.

News article on proposed tax reform by the Ecuadorian Congress in fall 1999.

-

(Alvaro 1999b) Alvaro, Mercedes. 1999b. “Ecuador’s October Tax Collection up to ECS1.743 Tln.” Dow Jones, December 9, 1999.

News article on Ecuadorian tax collection in October 1999.

-

(Alvaro and Tedesco 1999) Alvaro, Mercedes, and Enza Tedesco. 1999. “Growing Ecuador Bank Woes May Finally Force Consolidation.” Dow Jones, March 24, 1999.

News article on the deposit freeze in Ecuador.

-

(AP 1999) Associated Press (AP). 1999. “Ecuador Declares Surprise Bank Holiday to Protect Currency,” Associated Press, March 8, 1999.

News article on the surprise bank holiday in Ecuador.

-

(Crenson 1999) Crenson, Sharon L. 1999. “Ecuador Defaults on $6 Billion `Brady Bond’ Debt; Creditors Undecided on Options.” Associated Press, September 30, 1999.

News article covering Ecuador’s default on Brady bonds.

-

(Dow Jones 1998) Dow Jones. 1998. “Ecuador’s Banco De Prestamos, Continental In Merger Talks.” Dow Jones, August 24, 1998.

News article on liquidity problems with Banco de Prestamos.

-

(Dow Jones 1999a) Dow Jones. 1999a. “Ecuador Bank Accts Freeze -2: Decree Signed Thursday,” Dow Jones, March 12, 1999.

News article on the one-year freeze on deposits.

-

(Dow Jones 1999b) Dow Jones. 1999b. “Ecuador’s Central Bank Pegs Bank Withdrawals at 1.7 billion Sucres.” Dow Jones, March 30, 1999.

News article on March 30, 1999, containing a quote from then–CBE President Luis Jacome.

-

(Dow Jones 2007) Dow Jones. 2007. “Ecuador: Correa Supporter to Lead Constitutional Tribunal,” Dow Jones, June 5, 2007.

News article on Ecuador’s highest court during the blanket guarantee.

-

(EIU 2004) Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 2004. “Ecuador Risk: Financial Risk.” Accessed October 4, 2022, March 18, 2004.

News article on Ecuador’s financial risk.

-

(EIU 2009) Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). 2009. “Ecuador Finance: Bankers Oppose New Financial Security Law,” January 20, 2009.

News article on the transition from the AGD to COSEDE, highlighting opposition from bankers.

-

(El Comercio 2009) El Comercio. 2009. “La AGD se Cierra Luego de 11 Años.” El Comercio, December 31, 2009.

News article discussing the closure of the AGD (in Spanish).

-

(El Telégrafo 2014) El Telégrafo. 2014. “La crisis bancaria de 1999 Costó al País $ 6.170 Millones.” El Telégrafo, January 14, 2014.

News article discussing the results of Ecuador’s banking crisis (in Spanish).

-

(Global Insight Daily Analysis 2008) Global Insight Daily Analysis. 2008. “New Finance Sector Regulation in Ecuador Raises Fears over Bigger State Role.” Global Insight Daily Analysis, December 11, 2008.

News article on the transition from the AGD to COSEDE in December 2008.

-

(LatinFinance 2002) LatinFinance. 2002. “From Boom to Bust ... and Back Again? No Sector Better Typifies Ecuador’s Turbulent Economic Past than the Banking Sector. Stability Is Back, but Repairing Confidence Is Taking Time.” LatinFinance, March 1, 2002.

News article covering the process by which the AGD bailed out banks.

-

(Remond 1999) Remond, Carol S. 1999. “Ecuador, Creditors Meeting Seen Yielding Little Results.” Dow Jones Business News, November 10, 1999.

News article on Ecuador’s financial transaction tax.

-

(WSJ 1999) Wall Street Journal (WSJ). 1999. “International World Watch.” Wall Street Journal, March 31, 1999.

News article containing figures related to Ecuador’s deposit freeze.

-

(COSEDE 2014) Deposit Security Corporation (Corporación del Seguro de Depósitos, or COSEDE) (COSEDE). 2014. “Informe de Rendición de Cuentas.” March 24, 2014.

Report by COSEDE for the period 2013, containing information on the transfer of assets from the AGD to COSEDE’s new Deposit Insurance Fund (in Spanish).

-

(IMF 2000a) International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2000a. “Ecuador—Staff Report for the 2000 Article IV Consultation, Material for the First Review under Stand-By Arrangement; and Exchange System.” Report No. EBS/00/164, August 14, 2000.

Staff report by the International Monetary Fund for the 2000 Article IV consultation with Ecuador.

-

(Jácome H. 2004) Jácome H., Luis Ignacio. 2004. “The Late 1990s Financial Crisis in Ecuador: Institutional Weaknesses, Fiscal Rigidities, and Financial Dollarization at Work.” International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 04/12, January 2004.

Working paper examining Ecuador’s blanket guarantee.

-

(Republic of Ecuador 2000b) Republic of Ecuador. 2000b. “Listing Particulars Document.” August 23, 2000.

Bond prospectus filed on behalf of the Republic of Ecuador with the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

-

(Beckerman and Solimano 2002) Beckerman, Paul, and Andrés Solimano. eds. 2002. Crisis and Dollarization in Ecuador: Stability, Growth, and Social Equity. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Book analyzing Ecuador’s cycles of crisis and stabilization attempts during the late 1990s.

-

(de la Torre, García-Saltos, and Mascaró 2001) Torre, Augusto de la, Roberto García-Saltos, and Yira Mascaró. 2001. “Banking, Currency, and Debt Meltdown: Ecuador Crisis in the Late 1990s,” October 2001.

World Bank paper discussing Ecuador’s financial crisis.

-

(IMF 2000b) International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2000b. “Ecuador: Selected Issues and Statistical Annex.” IMF Staff Country Report No. 00/125, October 2000.

Excerpt from an IMF docment discussing Ecuador’s financial sitution during the crisis.

-

(Martinez 2006) Martinez, Gabriel X. 2006. “The Political Economy of the Ecuadorian Financial Crisis.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 30, no. 4: 567–85.

Academic paper examining Ecuador’s banking collapse.

Figure 4: Timeline of Events and Interventions

Note: The runs described above were not discrete incidences but rather a continuous problem that Ecuador faced. This timeline provides some benchmark dates and events to conceptualize the evolution of the crisis.

Sources: Alvaro and Tedesco 1999; AP 1999; El Comercio 2009; El Telégrafo 2014; IMF 2000a, 28; IMF 2000b, 32; Jácome H. 2004, 17, 19–20, 23, 29–30, 35; Republic of Ecuador 2000b, 2, 15, 56, 59; WSJ 1999.

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Blanket Guarantee Programs

Countries and Regions:

- Ecuador

Crises:

- Ecaudorian Banking Crisis 1990s