Market Support Programs

Canada: Government Bond Purchase Program

Purpose

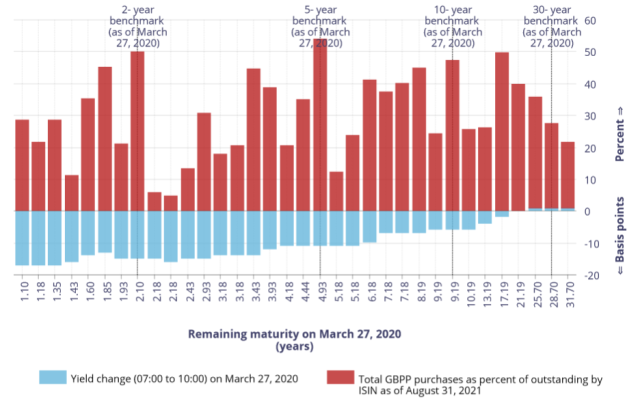

To “address strains in the Government of Canada bond market, and to enhance the effectiveness of other actions taken to support core funding markets. More recently, as market conditions improved, the focus of the GBPP has shifted to supporting the resumption of growth in output and employment” (BoC 2020a)

Key Terms

-

Launch DatesAnnounced: March 27, 2020

-

Operational DateApril 1, 2020

-

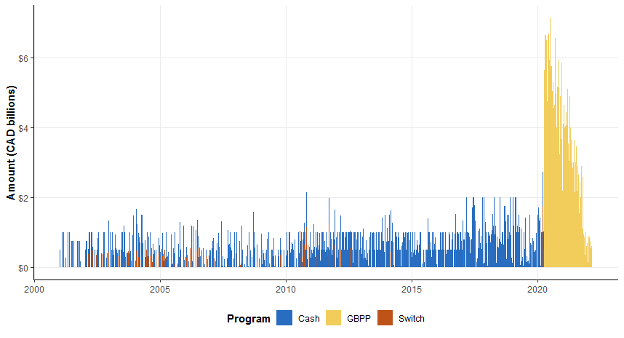

End DateChanged to quantitative easing in June 2020

-

Legal AuthorityBank of Canada Act, 18(c)

-

Source(s) of FundingBank of Canada balance sheet

-

AdministratorBank of Canada

-

Overall SizeNo fixed ceiling

-

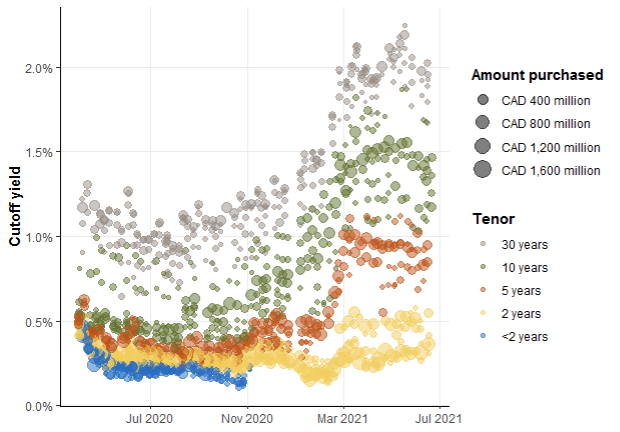

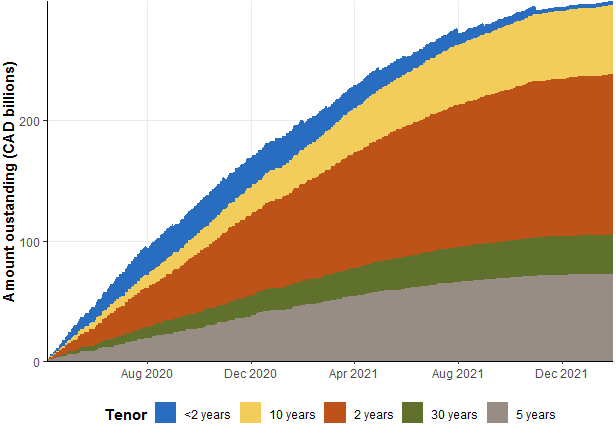

Eligible Collateral (or Purchased Assets)Secondary-market Government of Canada bonds of all tenors

-

Peak UtilizationCAD 64.7 billion on June 22, 2021

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

Part of a Package

Governance

Administration

Communication

Disclosure

SPV Involvement

Program Size

Source(s) of Funding

Eligible Institutions

Auction or Standing Facility

Loan or Purchase

Eligible Collateral or Assets

Loan Amounts (or Purchase Price)

Haircuts

Interest Rate

Fees

Term

Other Conditions

Regulatory Relief

International Cooperation

Duration

Key Program Documents

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Market Support Programs

Countries and Regions:

- Canada

Crises:

- COVID-19