Broad-Based Emergency Liquidity

Canada: Contingent Term Repo Facility

Purpose

“To counter any severe market-wide liquidity stresses and support the stability of the Canadian financial system”

Key Terms

-

Launch DatesAnnounced: March 20, 2020; Activated: April 6, 2020

-

Expiration DateApril 6, 2021

-

Legal AuthoritySubparagraph 18(g)(i) of the Bank of Canada Act

-

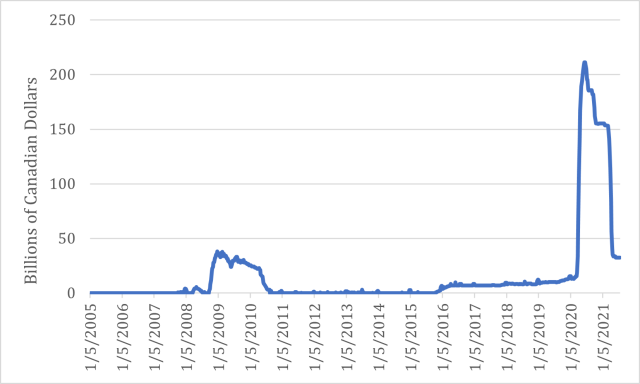

Peak OutstandingCAD 291.8 million of securities in Q2 2020

-

ParticipantsFinancial institutions subject to federal or provincial regulation that could prove significant activity in Canadian money or bond markets

-

RateConnected to the overnight swap index rate

-

CollateralSecurities issued or guaranteed by the government of Canada or a provincial government

-

Loan DurationOne month

-

Notable FeaturesSimilar to a Global Financial Crisis–era program

-

OutcomesCAD 291.8 million of securities from counterparties in Q2 2020

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

Part of a Package

Management

Administration

Eligible Participants

Funding Source

Program Size

Individual Participation Limits

Rate Charged

Eligible Collateral or Assets

Loan Duration

Other Conditions

Impact on Monetary Policy Transmission

Other Options

Similar Programs in Other Countries

Communication

Disclosure

Stigma Strategy

Exit Strategy

Key Program Documents

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Broad-Based Emergency Liquidity

Countries and Regions:

- Canada

Crises:

- COVID-19