Account Guarantee Programs

Australia: Financial Claims Scheme

Purpose

To “give depositors in an authorised deposit-taking institution or ADI, as the legislation describes it, prompt access to funds in the unlikely event that such a financial institution should fail” and to match deposit guarantees in other countries (Prime Minister of Australia 2008; Swan 2008b)

Key Terms

-

Launch DatesAnnouncement: Oct. 12, 2008; Authorization: Oct. 17, 2008; Operation: Nov. 28, 2008

-

End DateOriginally scheduled to be reviewed by Oct. 12, 2011. In 2010, revised and made permanent

-

Eligible InstitutionsAuthorized deposit-taking institutions (ADIs)

-

Eligible AccountsDeposit accounts held within ADIs

-

FeesNo fees were associated with the program, but the Australian government could impose industry-wide fees in the case of an ADI failure

-

Size of GuaranteeOriginally, unlimited. Then, AUD 1 million

-

CoverageAUD 650 billion in March 2009

-

OutcomesNo depositor claims made

-

Notable FeaturesParticipation in the unlimited guarantee was voluntary; The FCS had a complicated exercise process, which required the APRA to get approval from the Treasurer and courts; Although the FCS was subject to an AUD 1 million cap, another program was available to guarantee larger deposits for a fee; The FCS charged no fees, though the Australian government could impose industry-wide fees to cover any losses; The FCS also had a program that insured claims by general insurance policyholders

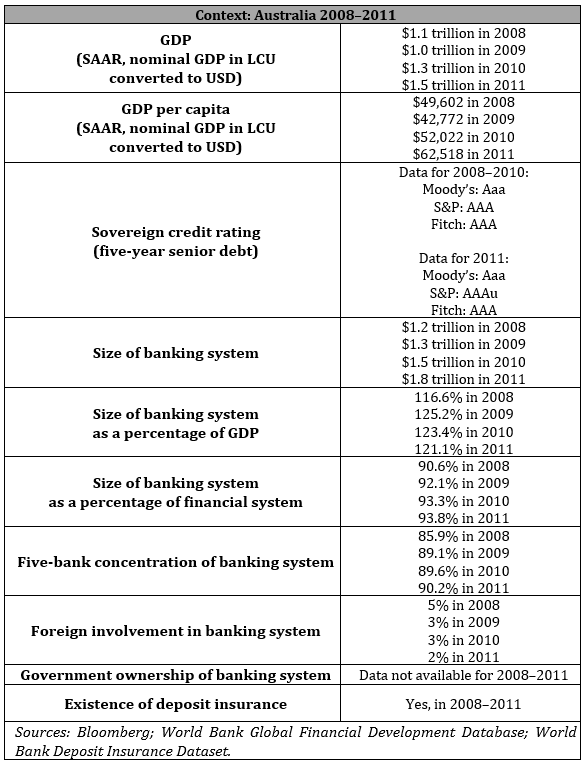

Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008, the Australian government intervened in its own banking system, both to support domestic depositors and to keep its banking system competitive with those in countries whose regulators had already intervened. On October 12, 2008, the Australian government announced the Financial Claims Scheme (FCS) to insure bank depositors. The deposit guarantee automatically insured depositors at all authorized deposit-taking institutions and covered a range of deposit accounts. As initially announced, the FCS would provide a blanket guarantee to all depositors with no fee for participation. This blanket guarantee, however, prompted a migration of funds from managed funds and investment banks to deposit accounts. On October 24, 2008, the government formally announced that an unlimited deposit guarantee would remain available, but in two parts. The FCS would guarantee up to AUD 1 million (about USD 660,000) per person per authorized deposit-taking institution, free of charge. A separate program would guarantee larger deposits for a fee on a voluntary basis. Prior to the FCS, Australia did not have a deposit-insurance scheme. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) ran the program. The FCS covered deposits totaling AUD 650 billion in March 2009. During its crisis operations, no depositor claims were made on the FCS. The government originally said it would review the cap after three years. In December 2010, the Australian government said the FCS would be a permanent feature of the Australian financial system. In February 2012, it lowered the guarantee to AUD 250,000.

Following the collapse of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008, financial uncertainty spread around the globe, leading to nervousness among some Australian depositors (RBA and APRA 2009). Although Australian banks had relatively little exposure to US assets, economic growth declined, unemployment rose, and uncertainty grew (RBA n.d.). In light of these factors, lending rates increased and there was increased competition for deposits (RBA and APRA 2009). On October 10, 2008, the Group of Seven, with the hope of bolstering depositor confidence, agreed that deposit guarantees around the world should be consistent (G-7 2008). The widespread panic prompted the Australian government to intervene in its banking system, both to support its domestic depositors and to maintain its international competitiveness (Australian Government 2012b; Rudd 2008). On October 12, 2008, the Australian government announced the Financial Claims Scheme (FCS). The FCS aimed to reassure depositors that they could access their funds quickly in the event of a bank’s failure, and to ensure that Australian banks remained internationally competitive (Swan 2008b).

The FCS automatically insured all authorized deposit-taking institutions (ADIs), including Australian-owned banks, Australian subsidiaries of foreign-owned banks, building societies, and credit unions (Prime Minister of Australia 2008). As initially announced, the guarantee was a blanket guarantee, with unlimited coverage and no fee for participation. This blanket guarantee resulted in market distortions, as market participants moved funds from managed funds and investment banks to deposit accounts (Swan 2008a; Bendeich 2008).

On October 24, 2008, the government formally announced that the FCS would guarantee AUD 1 million per person (about USD 660,000) per ADI, free of charge, and cover a range of deposits.FOn October 23, 2008, USD 1 = AUD 1.49, per Yahoo Finance. The purpose of this change was to limit market distortions associated with the guarantee (Swan 2008a). For deposits over AUD 1 million, depositors could be covered on a voluntary basis under the Guarantee Scheme for Large Deposits and Wholesale Funding (GS), which charged fees for the guarantee (Prime Minister of Australia 2008; Australian Treasury 2008c; Smith 2020). Prior to the FCS, Australia did not have a deposit-insurance scheme (Kerlin 2017, 291).

During the first three years of its operations, the government said it would appropriate an unlimited amount of funds to meet depositors’ entitlements if the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) had assumed control of their bank in a receivership. After that, a maximum budgetary appropriation of AUD 20 billion could be used to fulfill claims. The Australian government recognized that this AUD 20 billion fund would not cover the potential failure of its largest banks (FSB 2011). ADIs did not have to pay fees to receive coverage of the first AUD 1 million of a depositor’s entitlements under the FCS (Australian Treasury 2008c). To fund any FCS costs in excess of budgetary appropriation, disbursements were expected to be recovered through liquidation in receivership and through industry-wide fees imposed after an ADI’s failure.

The Australian government passed legislation empowering the APRA, the Australian bank regulator, to administer timely depositor payouts through the FCS; prior to the legislation, the APRA could only compensate depositors of a failed ADI after it had undergone liquidation—a potentially lengthy process (FCS Bill 2008a; APRA 2009).

The FCS covered deposits totaling AUD 650 billion in March 2009 (Australian Treasury 2008c; RBA and APRA 2009). During its crisis operations, no depositor claims were made on the FCS (APRA n.d.).

Originally, the FCS had no end date; the FCS’s guarantee cap was scheduled to be reexamined by October 12, 2011 (Prime Minister of Australia 2008). In December 2010, the Australian government decided to make the FCS a permanent feature of the Australian financial system (Australian Treasury 2010a). Until February 1, 2012, the FCS guaranteed AUD 1 million per person per ADI, free of charge. Afterward, the government lowered the guarantee to AUD 250,000 per person per ADI. A grandfathering provision also extended higher coverage for term deposits that existed on September 10, 2011 (Australian Government 2012b). Following its revision, the FCS continued to cover “99 per cent of deposit accounts in full, and about 50 per cent of eligible deposits by value” (Australian Treasury 2011; Turner 2011). Furthermore, the GS closed for new liabilities at the end of March 2010 and guaranteed liabilities until October 2015 (Australian Government 2012a).

The FCS was implemented to reassure depositors and ensure that Australian banks were not disadvantaged compared to their international counterparts (Prime Minister of Australia 2008; Swan 2008b). The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and APRA said that after the announcement of the FCS there was a “sharp increase” in deposit accounts at banks, which households perceived as relatively safer for their savings than investments in real estate or the stock market (RBA and APRA 2009). They also said that “there was a reversal in potentially destabilising deposit outflows from a number of ADIs that had been evident in early October.” Between October 12, 2008, and July 24, 2009, Australian banks of all sizes gained market share of deposits, with smaller and regional banks growing faster than the country’s four largest banks; depositors migrated to domestically owned banks from subsidiaries and branches of foreign-owned banks. The FCS, as originally announced on October 12, 2008, was also associated with market distortions, as market participants moved their funds to fully guaranteed deposit accounts (Bendeich 2008; Swan 2008a). Ultimately, this prompted the Australian government to limit the FCS’s free deposit coverage to AUD 1 million (Swan 2008a; Australian Treasury 2008c). The RBA, APRA, and others also found that credit unions and building societies lost market share of deposits in the months leading up to September 2008, but the announcement of the FCS stabilized those losses.

No banks made claims on the FCS, and the Australian economy emerged “relatively well” from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) (IMF 2012; Schwartz and Tan 2016). An insurance company, though, did make use of the FCS (Australian Treasury 2009; APRA n.d.). Scholars attributed the FCS’s relative success to the APRA’s prudential authority, which eliminated the need for an additional administrative body and avoided potential coordination problems (Turner 2011).

Despite its success, the FCS also faced several criticisms about its ex-post funding arrangement (IMF 2012). During the first three years of its operations, an unlimited amount of funds could be appropriated to meet depositor entitlements if their bank failed (FCS Bill 2008a). Following the first three years of the FCS’s operation, a maximum of AUD 20 billion could be used to fulfill claims (FCS Bill 2008a; APRA 2009). No fees were levied against ADIs covered by the FCS, though deposits in excess of the AUD 1 million cap could be guaranteed for a fee (Australian Treasury 2008c). Rather, FCS disbursements were expected to be recovered through receivership liquidation and through industry-wide fees that could be imposed after an ADI’s failure.

In a review shortly after the government made the FCS permanent, the IMF noted several aspects of the ex-post funding arrangement that were below industry standards (IMF 2012). First, the delayed funding could lead to delays in deposit repayment, which could reduce depositor confidence. A potential delay in repayment could be worsened by the limited forms of deposit repayments available under the FCS: “checks drawn on RBA, electronic transfers to accounts at another ADI, or other similar cash payments.” Second, the funding arrangement might contribute to moral-hazard concerns because ADIs might be inclined to take increased risks if they benefited from the FCS’s protection without paying fees.

The IMF also expressed concern about the potential unpredictability of the FCS’s execution procedure. After the APRA had applied to the Australian federal court, the FCS’s guarantee would be activated at the Australian Treasurer’s discretion (FCS Act 2008; Turner 2011). This wind-up process could lead to uncertainty about whether the courts would approve the APRA’s request and whether the Treasurer would activate the FCS; if either process failed, it could hurt depositor confidence and lead to bank runs.

To help Australian authorities improve the FCS, the IMF recommended that they reevaluate the merits of an ex-ante funding scheme and create a more straightforward wind-up process. The IMF reiterated this recommendation in 2019. Australian officials, however, did not support the IMF’s recommendation (IMF MCMD 2019).

Key Design Decisions

Purpose

1

By June 2008, the Australian government had begun work on the Financial Claims Scheme (FCS), which was meant to protect depositors’ funds (Swan 2008b; Australian Treasury 2008b; Australian Treasury 2008a). By September 2008, the RBA reported that the government intended to guarantee AUD 20,000 and expected to pass the requisite legislation by year-end 2008 (RBA 2008b). The RBA attributed the delay between the announcement and the government’s expected action to the investigation of technical issues associated with the scheme (RBA 2008a).

On October 10, 2008, the Group of Seven urged countries to maintain robust and consistent deposit-insurance systems (G-7 2008). On October 12, 2008, amidst the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the Australian government officially announced the FCS. The scheme was conceived as a response to actions taken by international competitors (Rudd 2008; Prime Minister of Australia 2008). As initially announced, the FCS provided a blanket guarantee to all depositors with no fee for participation. The government also announced on that day a guarantee scheme for banks’ non-deposit wholesale term funding.

Part of a Package

1

Originally, the government announced that it would provide a blanket guarantee to all depositors with no fee for participation. However, this announcement led to market distortions, as market participants moved their funds into guaranteed deposit accounts (Swan 2008a; Bendeich 2008). On October 22, 2008, Treasurer Wayne Swan said that, due to these market distortions, the Australian government had considered whether to cap the FCS’s free depositor protection.

On October 24, 2008, the government announced that an unlimited deposit guarantee would remain available, but in two parts. The FCS would guarantee AUD 1 million per person per authorized deposit-taking institution (ADI), free of charge (Australian Treasury 2008c). For deposits over AUD 1 million, depositors could be covered under the Guarantee Scheme for Large Deposits and Wholesale Funding (GS), which charged fees for the guarantee (Smith 2020). Both programs were meant to reassure depositors that they would have access to their funds if their banks failed. The government also expressed the intention to compete with countries that had announced similar guarantee programs (Australian Government 2012b).

Also, on October 12, 2008, the government announced the purchase of residential mortgage-backed securities to “benefit Australia’s mortgage market and ensure that this sector of the lending market [had] access to funding for its operations” (Prime Minister of Australia 2008). These purchases lasted until April 2013 and totaled AUD 20 billion (Reuters 2013).

In addition to guaranteeing deposits, the FCS insured general insurance policyholders through the Policyholder Compensation Facility (PCF) (APRA 2009). The Treasury had announced the PCF alongside the FCS’s depositor protections in June 2008 (Australian Treasury 2008b; Swan 2008b). The PCF allowed the APRA to appoint judicial managers to general insurance issuers and to provide policyholders access to funds to meet their insurance claims if their general insurer were to fail. The APRA said that such a facility was in the “interests of policyholders and financial system stability in Australia” (APRA 2009).

Legal Authority

1

The Australian government passed the Financial System Legislation Amendment (Financial Claims Scheme and Other Measures) Act of 2008 on October 17, 2008. This act created the FCS, authorized the APRA to administer it, and allowed regulators to set the deposit-insurance cap (FCS Act 2008; Prime Minister of Australia 2008). On November 3, 2008, the Treasury set the cap at AUD 1 million, with the cap coming into effect on November 28, 2008 (Banking Amendment Regulations 2008a; Banking Amendment Regulations 2008b). The government proposed the bill on October 15, 2008, and it passed both chambers of parliament without amendments (FCS Bill 2008b). Australian representatives expressed concerns with the bill during debate, such as moral-hazard concerns (Australian House of Representatives 2008).

The Australian government had begun work on the FCS in early 2008 (Swan 2008b; Australian Treasury 2008a; Australian Treasury 2008b). Treasurer Wayne Swan credited much of the FCS’s success to this pre-October 2008 work (Swan 2013). The FCS that was implemented in October 2008, however, differed from that prior plan (Australian Treasury 2010a). For instance, the prior plan would have had an AUD 20,000 insurance cap per depositor; the crisis-time FCS had a cap of AUD 1 million (Australian Treasury 2008b; Australian Treasury 2008c; RBA 2008b).

On December 12, 2010, the Australian government said it would make the FCS a permanent feature of the financial system (Australian Treasury 2010a).

Administration

1

The APRA was responsible for administering the FCS, pursuant to the amendments to the FCS Act of 2008 that the legislature passed in October 2008 (FCS Act 2008; Prime Minister of Australia 2008). The APRA was charged with protecting depositors, ensuring financial safety and efficiency, and promoting financial stability (Council of Financial Regulators 2008). The APRA was also responsible for assessing and advising ADIs while coordinating and communicating with ADIs in financial distress. Policymakers saw the APRA as best suited to administer the FCS. As Australia’s prudential bank regulator, it had the information needed to implement the FCS.

Governance

1

The Council of Financial Regulators, a body comprised of the APRA, the RBA, the Australian Treasury, and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, was also consulted to “coordinate policy actions aimed at ensuring the safety and efficiency of the financial system” (Turner 2011). The Council was instrumental in advocating for deposit insurance prior to 2008 and was the body that assessed whether the FCS should be modified after the financial crisis (Turner 2011; Council of Financial Regulators 2009). The Council and the Treasury also advised the APRA with respect to the FCS’s implementation (APRA 2009; Australian Treasury 2010b).

The IMF also conducted a report of the FCS and provided several policy recommendations. See the Evaluation section above for a discussion of the IMF’s report.

The Australian government exercised oversight powers over the FCS, determining the extent of its coverage and whether it would be made a permanent feature of the Australian banking system.

Communication

1

On October 12, 2008, the Australian government announced the FCS (Prime Minister of Australia 2008). The Australian government noted that the FCS was meant to reassure depositors in the face of economic uncertainty. Wayne Swan, the Treasurer of Australia, emphasized that the FCS was meant to protect small depositors and ensure that these depositors had access to their funds. Swan also stressed that the FCS was not intended to be a “general deposit insurance scheme” and that the FCS was not meant to shelter large-scale investors from risk, nor burden the banking system (Swan 2008b). Furthermore, then general manager of the APRA David Lewis emphasized that the FCS was not a “compensation scheme,” but rather a means to ensure that depositors could access their funds quickly (Lewis 2009).

The government framed the FCS, along with the other guarantee program, as a measure to ensure that Australian banks could compete with their international counterparts, many of which had benefited from emergency guarantee programs extended by host governments.

Prior to the GFC, in June 2008, the Australian government announced that it had begun work on the FCS, which was meant to protect depositors’ funds (Swan 2008b; Australian Treasury 2008a; Australian Treasury 2008b). By September 2008, the RBA reported that the government intended to guarantee AUD 20,000 and expected to pass the requisite legislation by year-end 2008 (RBA 2008b). The delay in the scheme’s adoption, RBA said, was due to an investigation of technical issues associated with the scheme (RBA 2008a).

According to the Council of Financial Regulators’ Memorandum of Understanding, adopted on September 18, 2008, the APRA was responsible for the communication of its supervisory actions and for the implementation of the FCS, even though the FCS remained unlegislated. The APRA also was responsible for communicating with ADIs, in the event of a “coordinated response” (Council of Financial Regulators 2008). The Treasurer and the Australian government, though, were responsible for communicating with the public about any resolutions, including the decision to exercise the FCS.

Size of Guarantee

1

On October 12, 2008, when the FCS was officially announced, there was “no limit on the deposits covered” (Prime Minister of Australia 2008). However, due to market distortions and advice from the Council of Financial Regulators, on October 24, 2008, the government decided to cap its deposit guarantee at AUD 1 million, with amounts over AUD 1 million eligible for coverage with a fee (Australian Treasury 2008c; Swan 2008a). Once the FCS became fully operational on November 28, 2008, the FCS guaranteed AUD 1 million per person per ADI, free of charge (Australian Treasury 2008c; RBA and APRA 2009). In March 2009, the FCS covered AUD 650 billion (RBA and APRA 2009). At its peak, in January 2010, the GS covered AUD 166 billion (Schwartz 2010).

On September 11, 2011, the government announced that it would lower the insurance cap to AUD 250,000 per person per ADI, free of charge, effective February 1, 2012 (Australian Government 2012b). A grandfathering provision also extended the AUD 1 million coverage for term deposits that existed on September 10, 2011, until the earlier of the maturity dates or December 31, 2012, and the new AUD 250,000 cap applied thereafter.

Source and Size of Funding

1

During its first three years of operation, the FCS was backed directly by taxpayers: The legislature would appropriate any amount of funds needed to meet depositor entitlements if their bank failed (FCS Bill 2008a). These taxpayer funds would come from the Consolidated Revenue Fund (APRA 2009). After its first three years, the legislation set a limit of AUD 20 billion on the amount the legislature could appropriate to fulfill depositor claims for a single failed bank. The APRA could also borrow, so long as the borrowed assets were channeled into the FCS Special Account.

When exercising the guarantee, the APRA would first draw upon the standing appropriation from the FCS Special Account (APRA 2009). Then, if necessary, the APRA could claim on the institution during its liquidation. If these funds were insufficient, then the APRA would apply an industry-wide fee to cover any shortfalls.

The IMF noted that this ex-post funding scheme could lead to delays in deposit repayment, which could reduce depositor confidence, and that the ex-post fees might contribute to moral-hazard concerns (IMF 2012).

Eligible Institutions

1

All ADIs, including Australian-owned banks, Australian subsidiaries of foreign-owned banks, building societies, and credit unions, were automatically enrolled in the FCS (Prime Minister of Australia 2008). The Treasury noted that deposit funding was critical for Australia’s small banks, credit unions, and building societies (Australian Treasury 2010a). In light of this importance, the Treasury asserted that without the FCS these institutions would have “had very substantial problems.”

The Australian Treasurer in October 2008 announced that foreign-bank branches would be able to access the guarantee of term wholesale funding and large deposits under the GS; however, they would not be eligible for the free guarantee of deposits below the AUD 1 million threshold under the FCS (Australian Treasury 2008c). The RBA in March 2009 noted that “deposits with foreign bank branches are not guaranteed under the Financial Claims Scheme” (RBA 2009). Foreign-bank branches were not eligible for depositor protections (FCS Act 2008).

Eligible Accounts

1

The FCS covered all deposit accounts held in ADIs (RBA and APRA 2009).

The FCS guaranteed AUD 1 million per person per ADI, free of charge. For deposits over AUD 1 million, depositors could be covered under the GS, which charged fees for the guarantee (Australian Treasury 2008c; Smith 2020).

Prior to becoming a permanent fixture of Australia’s financial system, the FCS underwent important changes via prudential standards (APRA 2011). For instance, the APRA required ADIs to identify individual account holders more carefully in order to make it easier to confirm depositors’ claims in a liquidation.

Fees

1

As an ex-post deposit guarantee, there were no fees for deposits within APRA’s maximum coverage limits (Turner 2011). A separate, voluntary insurance program for deposits over AUD 1 million did charge a fee (Australian Treasury 2008c). These fees were charged according to an institution’s credit rating, with the lowest fees set at 70 basis points per annum on covered deposits for AA-rated institutions (Schwartz 2010). A-rated institutions paid 100 basis points per annum on covered deposits, while BBB-rated and unrated institutions paid 150 basis points.

The Australian government also had the ability to impose industry-wide fees in the event that payments to deposits exceeded liquidation recoveries on the failure of an ADI (APRA 2009). In the case of an ex-post fee, the levy amount could not exceed 0.5% of an ADI’s liabilities to its depositors (ADI Levy Act 2008a; ADI Levy Act 2008b).

Process for Exercising Guarantee

1

In order to activate the FCS, the APRA was required to receive approval from the Australian courts that an ADI could be wound up (FCS Act 2008). In addition to the court’s approval, the Australian Treasurer was required to approve the FCS’s activation. This would activate the Early Access Facility for Depositors (FCS Bill 2008a). Once the FCS was activated, the APRA would assume control of the ADI.

Afterward, liquidation recoveries would repay the FCS.

Other Restrictions

1

The FCS had no additional conditions.FWhen the Australian Senate debated the FCS, Senator Bob Brown attempted to limit the salaries of all executives of guaranteed ADIs. Brown’s motion, though, failed (Australian Parliament 2008).

Duration

1

When it officially announced the FCS on October 12, 2008, the Australian government said it would review the need for a cap on the insurance level by October 12, 2011 (Prime Minister of Australia 2008). The Australian government in December 2010 said it would make the FCS a permanent feature of the Australian financial landscape (Turner 2011). Changes were made to the FCS in light of its permanent extension. After February 1, 2012, the FCS guaranteed AUD 250,000 per person per ADI, with no associated fee (Australian Government 2012b). The extended FCS also included a grandfathering provision, which extended greater coverage for certain deposits.

The GS closed for new liabilities at the end of March 2010 and guaranteed liabilities until October 2015 (Australian Government 2012a).

Key Program Documents

-

(APRA n.d.) Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). n.d. “APRA Explains—The Financial Claims Scheme,” accessed November 12, 2021.

Web page detailing the Financial Claims Scheme.

-

(Australian Government 2012a) Australian Government. 2012a. “Australian Government Guarantee Scheme for Large Deposits and Wholesale Funding.”

Web page about the Australian Government Guarantee Scheme for Large Deposits and Wholesale Funding.

-

(RBA n.d.) Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). n.d. “The Global Financial Crisis,” accessed November 12, 2021.

Explainer discussing the Global Financial Crisis, along with its effects on Australia.

-

(Australian Government 2012b) Australian Government. 2012b. “Questions and Answers about the Guarantee of Deposits.” Australian Government.

Web page with information about the Financial Claims Scheme.

-

(Council of Financial Regulators 2008) Council of Financial Regulators. 2008. “Memorandum of Understanding on Financial Distress Management Between the Members of the Council of Financial Regulators,” September 18, 2008.

Document detailing the division of responsibility in cases of financial downturn.

-

(ADI Levy Act 2008a) Financial Claims Scheme (ADIs) Levy Act (ADI Levy Act). 2008a. “Amount of Levy.” No. 103, §5.

Regulation setting out levy rules for the FCS.

-

(ADI Levy Act 2008b) Financial Claims Scheme (ADIs) Levy Act (ADI Levy Act). 2008b. Law establishing the FCS.

(ADI Levy Act 2008b) Financial Claims Scheme (ADIs) Levy Act (ADI Levy Act). 2008b. Law establishing the FCS.

-

(Australian House of Representatives 2008) Australian House of Representatives. 2008. “Commonwealth of Australia: Parliamentary Debates: House of Representatives.”

Document detailing parliamentary debate in the Australian House of Representatives.

-

(Australian Parliament 2008) Australian Parliament. 2008. “The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia: Journals of the Senate.”

Records of legislative proceedings in the Australian Parliament, including debates and motions.

-

(Banking Amendment Regulations 2008a) Banking Amendment Regulations. 2008a. No. 1, SLI No. 222.

Regulation determining the FCS’s threshold.

-

(Banking Amendment Regulations 2008b) Banking Amendment Regulations. 2008b. No. 1, SLI No. 222, Explanatory Statement.

Explanation of regulations about the FCS.

-

(FCS Act 2008) Financial System Legislation Amendment (Financial Claims Scheme and Other Measures) Act (FCS Act). 2008.

Legislation establishing the Financial Claims Scheme.

-

(FCS Bill 2008a) Financial System Legislation Amendment (Financial Claims Scheme and Other Measures) Bill (FCS Bill). 2008a. Explanatory Memorandum.

Explanatory document that accompanied the Financial Claims Scheme Bill.

-

(FCS Bill 2008b) Financial System Legislation Amendment (Financial Claims Scheme and Other Measures) Bill (FCS Bill). 2008b.

Financial Claims Scheme Bill before the act was passed into law.

-

(APRA 2011) Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). 2011. “APRA Releases New Prudential Standard for Financial Claims Scheme.” Press release, December 22, 2011.

Press release discussing new prudential standards, pertaining to the Financial Claims Scheme.

-

(Australian Treasury 2008a) Australian Government: The Treasury (Australian Treasury). 2008a. “Australian Response to International Recommendations on Financial Market Turbulence.” Press release, June 2, 2008.

Press release discussing Australia’s response to recommendations to improve its financial system.

-

(Australian Treasury 2008b) Australian Government: The Treasury (Australian Treasury). 2008b. “New Protections for Depositors and Policyholders.” Press release, June 2, 2008.

Press release highlighting new protections in Australia’s financial system.

-

(Australian Treasury 2008c) Australian Government: The Treasury (Australian Treasury). 2008c. “Government Announces Details of Deposit and Wholesale Funding Guarantees.” Press release, October 24, 2008.

Press release announcing the conditions of Australia’s Financial Claims Scheme.

-

(Australian Treasury 2009) Australian Government: The Treasury (Australian Treasury). 2009. “Financial Claims Scheme Policy Holder Compensation Facility Activated for Small General Insurer.” Press release, October 15, 2009.

Press release discussing the exercise of the FCS on a small insurer.

-

(Australian Treasury 2010a) Australian Government: The Treasury (Australian Treasury). 2010a. “Competitive and Sustainable Banking System Package.” Press conference, Canberra, December 12, 2010.

Press release discussing banking and competition in Australia.

-

(Australian Treasury 2011) Australian Government: The Treasury (Australian Treasury). 2011. “New Permanent Financial Claims Scheme Cap to Protect 99 Per Cent of Australian Deposit Accounts in Full.” Press release, September 11, 2011.

Press release announcing the permanent Financial Claims Scheme’s cap.

-

(G-7 2008) Group of Seven (G-7). 2008. “G-7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Plan of Action.” Press release, October 10, 2008.

Statement by the Group of Seven countries outlining their response to the GFC.

-

(Lewis 2009) Lewis, David. 2009. “Responding to the Global Financial Crisis—What’s on the Reform Agenda?” Speech delivered at the UBS Australian Financial Services Conference, Sydney, June 25, 2009.

Speech discussing the APRA’s response to the Global Financial Crisis and potential changes in light of the crisis.

-

(Prime Minister of Australia 2008) Prime Minister of Australia. 2008. “Global Financial Crisis.” Press release, October 12, 2008.

Press release by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd explaining Australian interventions in light of the GFC, including the FCS.

-

(Rudd 2008) Rudd, Kevin. 2008. “Interview with 60 Minutes, Channel Nine, Canberra.” October 12, 2008.

Interview in which Australia’s Prime Minister discussed the country’s guarantee.

-

(Swan 2008b) Swan, Wayne. 2008b. “Ministerial Statement on Financial Stability.” Address to the Australian House of Representatives, June 2, 2008.

Address given by the Minister of the Treasury regarding financial stability in Australia.

-

(Swan 2013) Swan, Wayne. 2013. “A Strong, Fair and Sustainable Financial System.” Address to the Bloomberg Australia Economic Summit, Sydney, April 10, 2013.

Address discussing the state of Australia’s financial system.

-

(Bendeich 2008) Bendeich, Mark. 2008. “Australian Funds in Crisis After Bank Guarantee.” Reuters, October 23, 2008.

Article discussing Australia’s original guarantee.

-

(Reuters 2013) Reuters. 2013. “Australia Ends A$20 Bln Mortgage-Backed Debt Buying Programme,” April 9, 2013.

News story announcing the end of Australia’s program to purchase mortgage-backed debt.

-

(Swan 2008a) Swan, Wayne. 2008a. “Treasurer Wayne Swan in the Hot Seat.” Interview by Kerry O’Brien. ABC News, October 22, 2208.

Interview discussing Australia’s guarantee program.

-

(IMF 2012) International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2012. “Australia: Financial Safety Net and Crisis Management Framework—Technical Note.” IMF Country Report No. 12/310, November 2012.

Report assessing Australia’s Financial Claims Scheme.

-

(Kerlin 2017) Kerlin, Jakub. 2017. The Role of Deposit Guarantee Schemes as a Financial Safety Net in the European Union. Warsaw: Palgrave Macmillan.

Book discussing deposit-insurance systems.

-

(Schwartz 2010) Schwartz, Carl. 2010. “The Australian Government Guarantee Scheme.” Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, March Quarter: 19–26.

Article discussing the Australian guarantee scheme.

-

(Schwartz and Tan 2016) Schwartz, Carl, and Nicholas Tan. 2016. “The Australian Government Guarantee Scheme: 2008–15.” Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, March Quarter: 39–46.

Article discussing the Australian guarantee scheme and its effects.

-

(Smith 2020) Smith, Ariel. 2020. “The Australian Government Guarantee Scheme for Large Deposits and Wholesale Funding (Australia GFC).” Journal of Financial Crises 2, no. 3: 576–92.

Case study examining Australia’s guarantee scheme, in response to the Global Financial Crisis.

-

(Turner 2011) Turner, Grant. 2011. “Depositor Protection in Australia.” Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, December Quarter: 45–56.

Article examining depositor insurance in Australia.

-

(APRA 2009) Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). 2009. Annual Report 2009.

Annual report discussing the APRA’s activities.

-

(Australian Treasury 2010b) Australian Government: The Treasury (Australian Treasury). 2010b. Annual Report: 2009–10. Australia: Department of the Treasury.

Annual report describing the Department of the Treasury’s activities.

-

(Council of Financial Regulators 2009) Council of Financial Regulators. 2009. Minutes of the Twenty-Seventh Meeting, June 19, 2009.

Report that discusses the extension of deposit insurance in Australia.

-

(FSB 2011) Financial Stability Board (FSB). 2011. “Peer Review of Australia: Review Report, September 21, 2011.”

Report examining Australia’s economic system.

-

(IMF MCMD 2019) International Monetary Fund Monetary and Capital Markets Department (IMF MCMD). 2019. “Australia: Financial Sector Assessment Program-Technical Note-Bank Resolution and Crisis Management.” IMF Country Report No. 19/48, February 2019.

IMF technical note discussing the Financial Claims Scheme.

-

(RBA 2008a) Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). 2008a. “Developments in the Financial System Infrastructure.” Financial Stability Review, March 2008.

Report discussing potential changes to the Australian financial system.

-

(RBA 2008b) Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). 2008b. Financial Stability Review, September 2008.

Review of Australia’s financial system.

-

(RBA 2009) Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). 2009. Financial Stability Review, March 2009.

Report assessing financial stability in Australia.

-

(RBA and APRA 2009) Reserve Bank of Australia and Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (RBA and APRA). 2009. “Inquiry by the Senate Economics References Committee into Bank Funding Guarantees—Joint Submission from the RBA and the APRA.”

Report considering the effects and efficacy of bank guarantees in Australia.

Taxonomy

Intervention Categories:

- Account Guarantee Programs

Countries and Regions:

- Australia

Crises:

- Global Financial Crisis